Are Boomers Bankrupting the Future?

Young people are paying disproportionately more tax in order to fund benefits for the wealthiest generation is history.

This episode of the Missing Middle podcast explores how Canada’s fiscal system has become increasingly tilted toward older generations, leaving millennials and Gen Z to face higher costs, fewer supports, and growing financial strain. Hosts Sabrina Maddeaux and Mike Moffatt break down how programs, tax credits, and health-care spending now overwhelmingly benefit seniors, even though they’re the wealthiest generation in Canadian history.

They also introduce the idea of “generational fairness” and discuss what reforms could rebalance the system without harming vulnerable seniors. The episode highlights what’s at stake for Canada’s future if the gap continues to widen and why all generations should care about fixing it.

If you enjoy the show and would like to support our work, please consider subscribing to our YouTube channel. The pod is also available on various audio-only platforms, including:

Below is an AI-generated transcript of the Missing Middle podcast, which has been lightly edited.

Mike Moffatt: Sabrina, today’s episode is something that you’ve written about a lot. There’s this persistent narrative that seniors are vulnerable and struggling, and we know many are. “Well, young people just need to work harder,” you might say, but when you look at the actual data on wealth or income or poverty rates across generations, what does it actually show?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Well, the data actually completely flips that narrative. Seniors today are nine times wealthier than millennials, and in the 1980s, that gap was only four times. Senior poverty is now just 5%, while child poverty is triple that.

Here’s the kicker. The average senior man actually earns more annually than the average man aged 25 to 34. Now, back in the 1970s, nearly 40% of seniors lived in poverty. So rightfully, we built programs like Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement to fix that. And the great news is we did.

The problem is that those programs haven’t evolved, even though seniors’ financial situation has completely transformed. Meanwhile, young families are more squeezed than ever, yet we’re still treating seniors like they’re the vulnerable ones.

So Mike, that makes me wonder: How much of the federal budget is actually eaten up by support for seniors? And were there any significant changes in Carney’s newly tabled budget?

Mike Moffatt: Well, they took off the luxury tax on yachts, so that might help some particularly wealthy seniors, but for the most part, they haven’t really changed support programs in one way or another. I mean, this was mostly a budget around national defence.

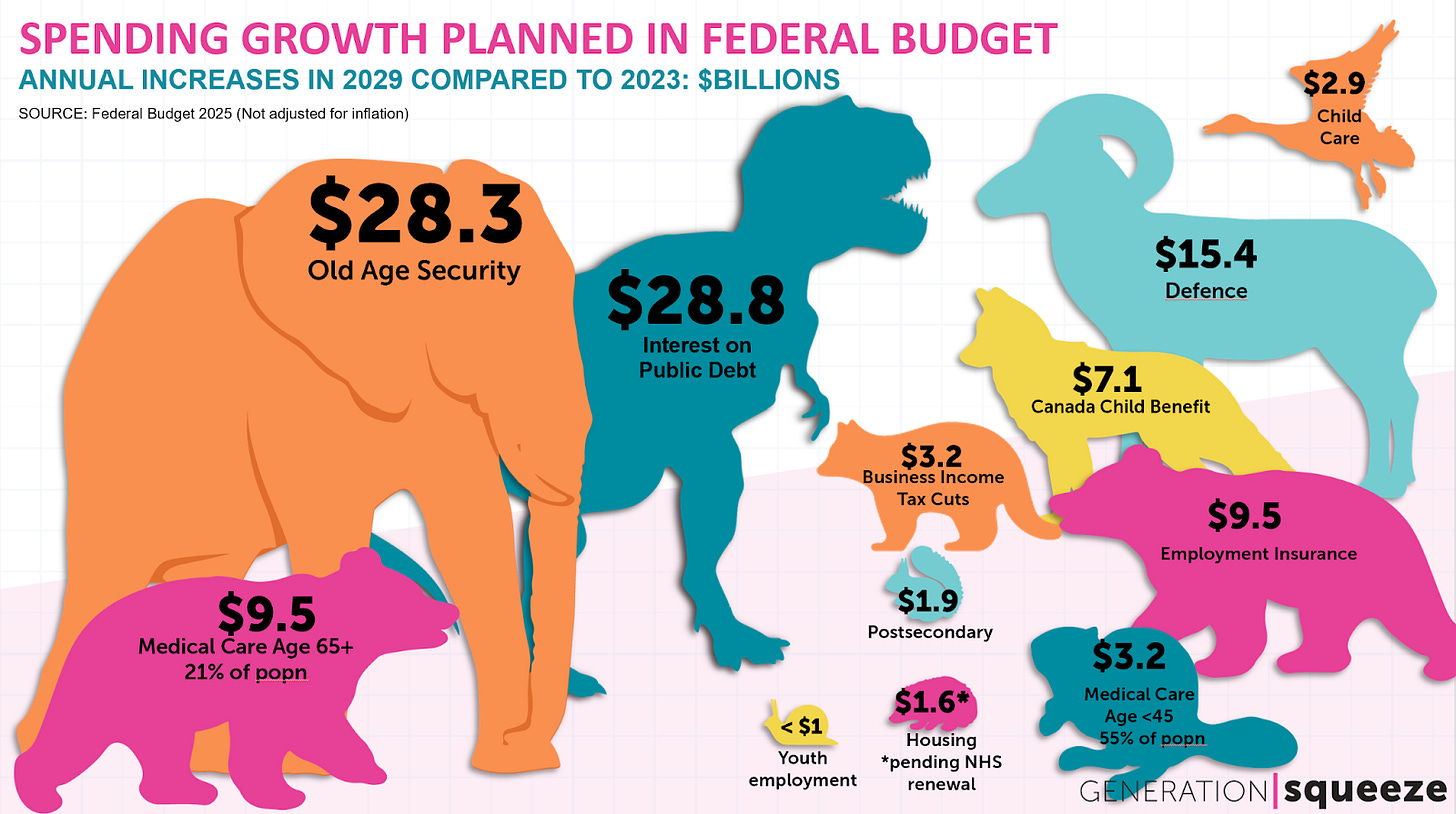

Now, when it comes to where additional dollars are going, our friends at Generation Squeeze have this fantastic infographic. It shows how much spending has gone up in certain categories. This great graph it’s got little pictures of animals on it that are proportional to the size of the changes. And big changes are the interest on public debt because both debts are going up, and interest rates are going up. That’s about $29 billion in additional spending in 2029 versus 2023.

After that, the next biggest line item is Old Age Security at $28 billion. That’s because these payments are indexed to inflation. We know the population of seniors is getting larger. That’s where a lot more of the money goes to.

The next biggest item is medical care for people over the age of 65 plus. Same issue there, that seniors are aging. As you get older, you need more medical care, and there’s a bigger cohort.

Other categories that look at things like post-secondary, youth employment and so on are much, much smaller pieces of the pie. So we see this trend that because there is a larger pool of seniors, because programs like OAS are fairly generous, and because seniors need more health care, an increasing portion of the budget, every single year, goes to these line items. So that’s what’s going on with the budget. We see a lot of that money going to seniors.

Sabrina, you’re part of a generation that’s experiencing financial stress at levels we haven’t seen in decades. So what does it feel like to be told that you need to tighten your belt while watching government resources flow overwhelmingly to the wealthiest generation in history?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Well, not great, Mike, to say the least.

So there’s a TD survey that shows 64% of Generation Z experience financial stress multiple times a week compared to just 27% of boomers. Only 55% of Gen Z believe they’ll retire comfortably.

I mean, the cost of living is crushing millennials and Gen Z, and both are the most educated generations in Canadian history, yet both are falling further and further behind. It’s not just about OAS; it’s the entire system. Seniors get major tax advantages, which are effectively subsidies paid for by younger taxpayers. We graduate with massive student debt into precarious jobs with no pensions. Housing costs seven to 10 times our income instead of three to four times as boomers had. Then we’re told we need to pay more taxes to fund benefits for a generation that’s wealthier than we’ll ever be.

Mike Moffatt: So, earlier I mentioned health care and how health-care federal spending is going up, but we also have to recognize that a lot of that spending is happening on the provincial level. So, if we look across federal and provincial spending, how much more does the health-care system spend on seniors versus younger Canadians? And where are those dollars coming from?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Yeah, this is where the intergenerational transfer really hits hard. Seniors account for about 46% of all health-care spending in Canada, despite being only 16 to 17% of the population. Per capita health-care spending for seniors is about five times higher than for younger Canadians, about 11,600 for seniors versus 2,700 for those under 65. That gap just continues to grow with age.

Now here’s the kicker. When boomers were young adults, there were nearly seven working-age Canadians for every senior. Today, there are only 3.3. Governments never adjusted the tax system to account for that change.

So a young worker earning $50,000 a year pays about $650 more per year for retirees’ medical care than a boomer at the same income level did when they were younger. So that’s clearly not sustainable.

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, and it really goes back to that book, “Boom, Bust and Echo,” and how demographics are two-thirds of everything. We’re seeing this ratio of young people to seniors, and how it’s affecting government spending through these indirect means.

There’s also the structure of the tax system that we need to look at. There’s this whole architecture of tax policy. Because, as we know, you could have two people who are both earning $100,000, but they could pay very different amounts in tax depending on how that income is structured, what expenses they have, and so on.

I know this is something that you’ve looked into, how the tax system is structured in a way that it’s disproportionately against younger workers and often at the benefit of seniors in ways that most people don’t see. So, can you walk us through what you found and your thinking on this?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Well, the thing is, two people earning $100,000 income in a year could pay vastly different amounts simply based on their age. So, beyond just OAS and health care, there’s a massive system of tax advantages for seniors.

For example, pension income splitting lets senior couples shift income to the lower earner, which dramatically reduces their tax burden — something that younger couples can’t do with employment income. There’s the age amount tax credit, which is once you turn 65, you automatically get a tax credit worth over $9,000 in income that you don’t have to pay taxes on, just for being over 65.

The pension income amount lets you claim up to $2,000 as a credit. On top of that, many provinces offer property tax reductions for seniors, and the biggest one is the principal residence exemption, which means that all those home price gains, which disproportionately went to seniors and that wealth that’s locking younger people out of home ownership, are completely tax-free when seniors sell.

Meanwhile, young people face the tax on split-income rules that prevent income splitting for business owners’ families. They pay full freight on student loans with no tax deduction. Their precarious employment often means no workplace benefits or pension contributions.

The tax code seems to be structured around the assumption that you’ll have stable employment, buy a home young, and retire comfortably with a pension, but the problem is that’s the exact opposite of millennials’ and Gen Z’s reality.

Mike Moffatt: So earlier in the episode, I talked about our good friends at Generation Squeeze, and they have this concept that they call generational fairness, and they have some metrics around that. So what does that actually mean, and why does it matter?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Yeah, Generation Squeeze, which was founded by UBC professor Paul Kershaw, has become a leading voice on this issue. His key insight is that we have this broken generational system where older Canadians benefited from past policy decisions that now actively harm their kids and grandkids.

So when boomers were young, housing was affordable, tuition was low, and there were plenty of good jobs with pensions. Plus, the tax burden for supporting retirees was much lower. They got to build wealth.

Now they’re asking their kids, who face the opposite conditions, to find an ever-expanding system of benefits and entitlements through higher taxes. This has resulted in us being one of the least generationally fair countries in the entire world.

Now, the goal in generational fairness isn’t to hurt seniors. It’s important to underline that. It’s to redesign our fiscal system so it doesn’t systematically extract from younger generations to subsidize older ones who are, on average, doing much, much better financially.

Mike Moffatt: So one of the things I like to do is read our YouTube comments section, and yes, I do read it. The whole team reads it. We don’t always respond, but we do appreciate the comments that you leave.

One that we see from time to time is that, “Well, Mike and Sabrina, you guys are always talking about problems, how broken things are, but often I’m not hearing about solutions.” So let’s give the audience what it wants, a little bit of audience love here, and talk about what meaningful reform would actually look like. How do we fix this system without abandoning vulnerable seniors who generally need the support?

Sabrina Maddeaux: There’s a lot of work to do, but some top-line items, OAS is a big one. Essentially, we need to make sure that seniors, of course, stay out of poverty, but we should not be funding their luxury retirements because that’s not the point of these policies, and it’s really hurting younger generations and putting them in a position where they’re going to be paying off this debt for years and years to come. OAS should be cut off at the average income of Canadians of all ages.

On top of that, we should have things like income splitting for younger Canadians, more tax benefits for young families. At the same time, it’s not just about benefits that directly cater to young people, but set up the conditions for small businesses, for tech businesses, and startups to thrive in ways that hopefully everyone’s incomes rise. Where they’re hiring more young workers, where if you want to start a business, you can do that without being overburdened by our tax system and incentivizing increased wages, increased investments in training young people, and hiring young people.

There’s so much work to be done, but unfortunately, the boomers have been incredibly politically powerful, and part of that is because there’s so much wealth concentrated there while young people are struggling, juggling two to three jobs and don’t have the money to come out and donate to political parties or to come out to afternoon meetings and participate politically as much as older people do. So I’m curious about your thoughts on this.

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, it’s a challenge. It’s one of those areas where good policy isn’t necessarily good politics and the other way around. One of the reasons why these programs are so generous to seniors is that, first of all, there are a lot of seniors, and they disproportionately vote. So the political system naturally caters to them in a way that it doesn’t necessarily do to other generations. So that is difficult, and it does show why younger voters do need to vote to balance out the system a little bit.

I’m also a big fan of the idea of the housing theory of everything. So if we could solve the housing system, get home prices back to reasonable levels, I think that doesn’t fix everything, but it fixes a lot of it. It gets young people to a point where they can own their own home, they can start saving up and so on.

Clearly, this is something that you’ve been thinking about quite a lot. So what do you think is at stake for Canada if we don’t address this? What does our country look like 5, 10, 20 years down the line if we continue on this path? And why should baby boomers and seniors care if your generation is not happy with how things are going?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Well, the future doesn’t look good if we don’t fix this. I would hope that seniors care about the future of the country that their kids, grandkids and great grandkids are going to live in. If we don’t fix this, we’re looking at a future where intergenerational resentment hardens, social cohesion breaks down, and our fiscal situation becomes truly untenable.

Young Canadians are already delaying or abandoning major life milestones because they can’t afford them. That has huge implications for our economy, our demographics and our overall social fabric.

Provincial deficits will keep growing as health-care costs explode. Public health care itself could be at risk if younger Canadians feel they’re being squeezed to subsidize boomers while getting absolutely nothing themselves. In fact, not just getting nothing themselves, but being actively extracted from.

Political support for senior supports, even the ones that are needed to keep seniors out of poverty, might drastically erode. We could also see increased emigration of talented young people to places with better opportunities. We’re already seeing that, and the choice is clear: either we modernize our fiscal system to be fair for all generations, or we continue extracting from the young to subsidize the old until the system breaks.

The good news, though, is we can fix this, but it requires political courage, and it also requires older Canadians themselves to practice through intergenerational solidarity and say, “I want to be a good ancestor. I want to leave my grandchildren better off, not worse off.”

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, I think that would create a much better system, and I have to admit, as a Gen Xer, I do love seeing baby boomers and millennials battle each other. Sometimes it warms my heart as the forgotten middle child of generations. But I think Canada works better when we’re all rowing in the same direction.

We’re creating a country that works for everyone and avoiding this level of intergenerational conflict. So I’m very grateful that you do this work. I love the op-eds and the Toronto Star, and we hope that seniors don’t necessarily take it too personally and realize that it is in their best interest as well that we create a country that works for all.

Sabrina Maddeaux: Yes, less intergenerational Fight Club, more intergenerational cooperation.

Thank you, everyone, for watching and listening and to our producer, Meredith Martin.

Mike Moffatt: Now, if you have any thoughts or questions about Fight Club, please send us an email to [email protected].

Sabrina Maddeaux: And we’ll see you next time.

Mike Moffatt: But we won’t answer those questions because of the first rule of Fight Club…

Sabrina Maddeaux: ...is you don’t talk about Fight Club.

Mike Moffatt: Exactly.

Research Links/Additional Reading:

After years of decline, child poverty in Canada is rising swiftly: report

Who is being asked to sacrifice in Budget 2025?

Globe and Mail - “How younger Canadians end up paying more for boomers’ medical care”

Macleans - “Seniors and the generation spending gap”

CBC - “A trillion-dollar tsunami: Canadians grapple with unprecedented wealth transfer”

Canadian Institute of Health Information - National Health Expenditure Trends:

This podcast is funded by the Neptis Foundation

Brought to you by the Missing Middle Initiative