Build Canada Homes Just Got Clearer... And More Concerning

New details confirm BCH’s ambitions and its troubling limitations.

Highlights

The purpose of Build Canada Homes (BCH) is now clearer: The new Investment Policy Framework released this weekend confirms BCH’s core mission: financing, building, and industrializing social and mixed-income housing on federal lands, with a strong tilt toward modern construction methods.

BCH’s design choices skew heavily toward small, low-rise homes: By prioritizing standardized designs from the CMHC Housing Design Catalogue, almost all 1-3 storey buildings with very few family-sized units, BCH risks deepening Canada’s shortage of three-bedroom and larger homes.

BCH lacks the tools needed to drive homebuilding in innovation: The Framework acknowledges the need for modern construction methods but offers only procurement (a PULL tool), with no complementary PUSH or GROW supports, pushing new technologies into a familiar “valley of death.”

Regulatory barriers remain the elephant in the room: BCH assumes that new technologies can be adopted once they reach scale, overlooking that zoning and building codes often make the most promising innovations illegal to build.

BCH offers a welcome, common-sense affordability definition, but its goals are unclear: BCH provides one of the clearest income-based affordability definitions in federal housing policy, yet the Framework still lacks clear federal objectives, raising the risk of federal dollars being spread, in the view of one observer, “a mile wide and an inch deep” without improving affordability.

Few things are quieter than a government release on a Saturday

We give many presentations about housing across Canada, and the most frequent question we get is some variant of “what exactly is this Build Canada Homes thing, anyway?” Canadians, even those in homebuilding, struggle to understand what the program is, how it works, or what it’s meant to accomplish.

Our job explaining Build Canada Homes (BCH) just became a tiny bit easier. Over the weekend, the federal government very quietly released the Build Canada Homes Investment Policy Framework, which provides additional details on how the program works and is meant to accomplish. The intended audience of the framework is potential government partners, such as non-profit and community housing providers and offsite housing manufacturers, but there are valuable insights for anyone interested in BCH.

Here are our six takeaways from the Build Canada Homes Investment Policy Framework.

What we learned about Build Canada Homes

1. What Build Canada Homes is meant to accomplish.

The framework provides the clearest explanation yet of the purpose of BCH, which is given at the top of Page 2 in a section titled "What Does Build Canada Homes Do?"

• Finance: Deploys public capital and attracts investment from private, philanthropic, and other orders of government to back impactful mixed income and affordable housing projects proposed by public, non-profit, Indigenous and private proponents.

• Build: Accelerates development on federal lands and structures transactions that reduce the cost to construct and shorten delivery timelines, including through direct development activities and public-private partnerships.

• Industrialize: Drives the housing sector’s adoption of modern methods of construction— including, but not limited to, factory-built housing, standard designs, mass timber, building information modelling (BIM), low-carbon materials, kit-of-parts approaches, and rapid assembly.

In other words, BCH is a program designed to work with non-governmental partners to build social housing on federally owned land, prioritizing modern construction methods such as mass timber and factory-built homes.

It is not a program designed to directly accelerate market-rate rental construction or ownership opportunities for middle-class families, though it may have some positive indirect effects on those markets by accelerating the use of new technologies.

2. Either by accident or by design, BCH prioritizes building small, low-density homes.

The federal government had been clear on BCH’s goal to build social housing, but they had been less clear on the types of homes they had in mind. Are they intending to build high-rise apartments? Accessory dwelling units? Three- and four-bedroom homes for families? Smaller units designed for those who have fallen into, or risk falling into, homelessness? The goals are unclear.

The framework helps flesh out the government’s vision through repeated references to “standard designs” on pages 2 and 6. Page 6 also makes it clear that a goal of BCH is to increase the use of the CMHC’s housing design catalogue:

BCH encourages proponents to leverage the Housing Design Catalogue where appropriate. The Catalogue offers over 50 regionally tailored, standardized designs that are affordable, efficient, accessible and sustainable, helping streamline project delivery and reduce design costs.

Those references are noteworthy, as the Housing Design Catalogue prioritizes small homes in 1-3 storey buildings. For example, the CMHC’s Housing Design Catalogue contains the following seven options for Ontario:

Figure 1: CMHC Housing design catalogue options for Ontario

Source: CMHC’s Housing Design Catalogue.

None of these seven buildings is taller than three storeys. Of the 21 units in these seven buildings, only five have three or more bedrooms.

Given that Canada has a substantial shortage of three-bedroom and larger homes, and the need for our cities to densify, BCH’s prioritization of small, low-rise homes is a peculiar choice.

3. It remains unclear how BCH will assess the trade-offs between affordability and innovation

Build Canada Homes encourages the use of “modern methods of construction”, recognizing that if builders and developers use them on BCH-funded projects, they are more likely to adopt them on non-BCH projects, and the cost of deploying these technologies will fall through learning-by-doing and economies of scale.

Government procurement as a tool to drive private-sector innovation has a long history, with both successes and failures. However, it comes with the recognition that, at least in the short run, innovative methods are more expensive than traditional approaches. For BCH, that means the more they focus on innovation, the fewer units they can acquire per million dollars. It is still unclear how BCH will navigate this trade-off.

4. The federal government continues to lack an innovation plan for housing, which condemns new technologies and companies to a “valley of death”.

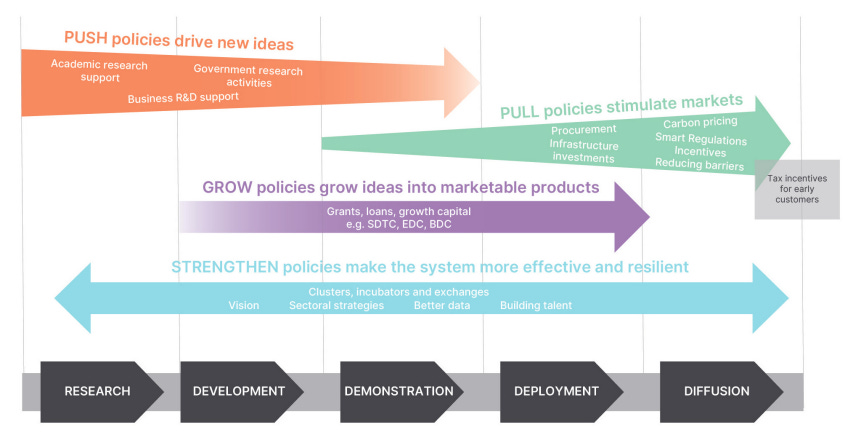

For a builder or developer to use a modern method of construction, the technology and the company providing it must be far enough down the innovation pathway that procurement (a PULL policy) can help it reach scale.

Figure 2: Clean Innovation Pathway

Source: Smart Prosperity Leaders’ Initiative.

However, the federal government currently lacks dedicated PUSH, GROW, and STRENGTHEN policies to accelerate innovation in homebuilding. The investment policy framework makes it explicit that BCH’s only housing innovation tool is procurement, and innovators requiring other forms of support should look elsewhere:

BCH will only consider investments to the extent that they support its core mandate of directly increasing the amount of affordable housing in Canada. This means that business support for technology or other capital needs are not in scope, unless they are needed to directly support a proposed delivery of affordable housing or portfolio of projects. Proponents seeking support for broader business development, technological innovation, or capital expansion are encouraged to engage with their Regional Development Agencies or explore opportunities through Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada’s new Strategic Response Fund, which are better suited to support these types of initiatives.

There is a grab bag of policies that can help innovators, but they are difficult to navigate, and there is no overarching structure to ensure these dollars are delivered in the most effective way possible. A recent piece in iPolitics calls for the federal government to provide dedicated innovation funding through BCH, and notes that without it, innovations are unlikely to make it to the deployment stage:

What’s missing from this budget is a dedicated innovation stream within Build Canada Homes. One designed to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) developing technologies that can transform how homes are built. These firms have the agility to pilot new methods, test advanced materials, and integrate manufacturing approaches that dramatically reduce costs and timelines. Without targeted funding for innovation, many of these solutions will remain trapped in pilot stages, a familiar “valley of death” that prevents promising technologies from scaling up and delivering impact.

A lack of support for early-stage innovation is not the only policy gap in Build Canada Homes' homebuilding innovation approach.

5. There also continues to be a lack of recognition of the role regulatory barriers play in housing innovation.

Both Build Canada Homes and the Housing Design Catalogue implicitly assume that any potentially useful homebuilding innovation could be adopted, and that governments can facilitate that adoption by helping those technologies reach scale and become cost-competitive with existing technologies.

While in many cases cost and scale are the primary barriers to adoption, in many others, regulatory barriers make adoption insurmountable. After all, you can’t adopt what’s not legal, and building codes and zoning rules are based on existing technologies. An innovator can develop a fire prevention system that is safer, lower-cost, and allows for more family-friendly housing layouts than existing approaches, but a builder or developer would be unable to adopt it due to building code rules or other standards.

For example, the book “Impossible Toronto,” provides a minimum of 14 different regulatory reasons why fantastic European courtyard-style apartments are illegal to build in the City of Toronto.

Figure 3: Impossible Toronto - Matrix of Impossibilities

Chart Source: Impossible Toronto.

Because BCH and the design catalogue are based on rules and regulations as they are today, and the federal government lacks an agenda to modernize these rules, Canada’s performance in innovative homebuilding will continue to lag.

6. BCH provides a common-sense, income-based definition of affordability. This is a good thing.

At the Missing Middle, we are fans of defining the terms we use, as we find that a substantial portion of housing policy debates are simply groups talking past each other, due to a lack of a common vocabulary.

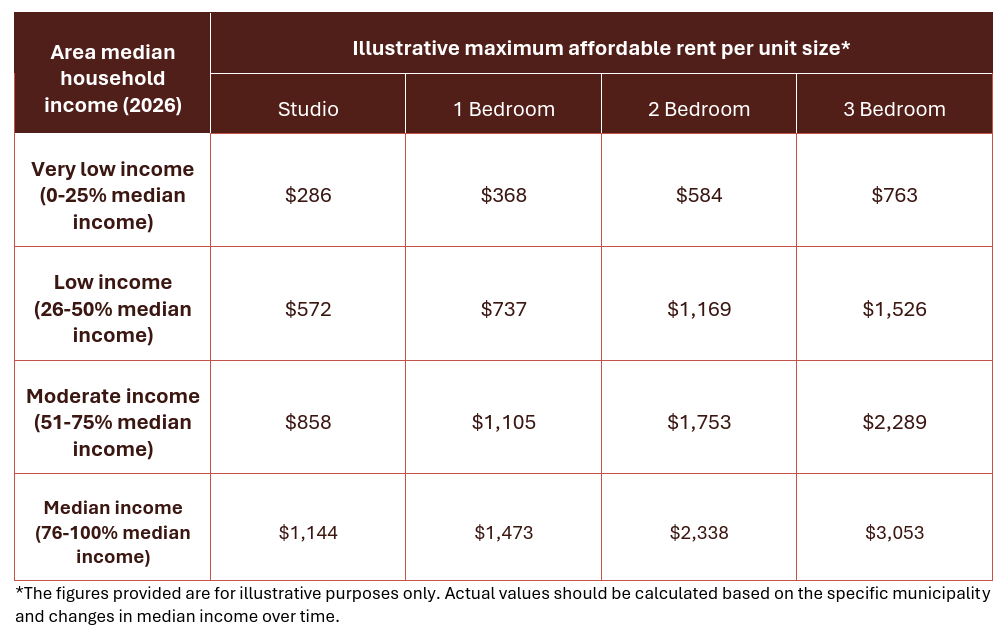

The most obvious question in any discussion of affordable housing is “how do you define affordable?” The policy framework provides an exceptionally detailed and common-sense definition of affordability. It examines the median income of a particular community and then creates four affordability tranches, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: BCH examples of affordability definitions (note: the exact amounts differ by community)

Source: Investment Policy Framework

We wish all government documents adopted this level of common sense and clarity when defining terms.

There is value in clarity

We are grateful to the federal government for releasing this framework. The transparency and clarity provided by the Investment Policy Framework do a fantastic job of highlighting BCH's strengths and the areas where more work is needed. Our views of this framework are aligned with those provided by Tim Richter from the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness:

However, the framework betrays a significant weakness in federal housing policy - a lack of clear objectives and desired outcomes. This framework is designed to respond to municipal, provincial, sectoral or proponent priorities versus proactively trying to achieve national housing affordability outcomes. BCH will very quickly be over subscribed with good projects and they could spend every dime allocated to them, end up spreading federal dollars a mile wide and an inch deep, and housing affordability and homelessness will not improve. If the federal government wants to improve housing affordability and reduce homelessness they need more focus in their policy. And BCH alone will not be able to solve the housing crisis.

The BCH framework is indicative of a ‘Ready, Fire. Aim.’ Federal housing policy. It is great for its clarity, but it’s not nested in a clear federal policy with clear outcomes or objectives so it’s effectiveness will be limited.

Let’s hope that future policy reforms and budgets create clear federal policies with clear outcomes and objectives that Canada’s housing sector truly needs.