Canada needed to add 500,000 homes last year to keep up with population growth. It failed to hit even half of that.

We're adding a lot of households, but not that many houses.

Welcome to the first-ever installment of the Canadian Housing Microresearch Project (CHMP). Today, we examine how Canada’s population grew by over 500,000 households last year while adding fewer than 250,000 houses.

Canada’s population grew by over 1.2 million people last year. To keep up with this growth, the country needed to add at least 500,000 homes to its housing stock. Instead, we added less than half of that, increasing Canada’s housing shortage by 250,000 units.

Nowhere was this disconnect between population growth and housing supply more acute than in Ontario. The province grew by 500,000 people, experiencing roughly the same population growth rate as the rest of Canada. To keep up with that growth, it should have added over 200,000 homes, but it added only 82,000, less than 40% of what it needed. This disconnect, which has been occurring for several years, is the primary contributor to the housing crisis.

Here is the math behind these estimates.

It should be uncontroversial to say that if a place’s population is growing, it will need more homes. But how many more homes?

As we wrote in the report, Ontario’s need for 1.7 million more homes, the relationship between the size of a population and the number of homes it needs can be complex:

Converting [an] increase in population to an estimate of the number of future households (and, therefore, the number of new homes needed) is not straightforward. This conversion is not an easy process; there is no one-to-one relationship between population growth and the growth in the number of households. For example, a family welcoming a second child increases the population but does not increase the number of households. A young adult moving out of their parents’ home into an apartment increases the number of households but does not increase the population. The number of households is a function of the size of the population, the age of the population, as well as the number of housing units available.

In order to estimate the number of housing units a place needs based on the size and age distribution of the population, we invented a blunt but surprisingly effective tool called the RoCA Benchmark that can generate an estimate of how many homes a place needs:

RoCA Benchmark Number of Households (Definition): The number of households a community would have, given the size of their population if their age-adjusted headship rates were equal to the 2016 “Rest-of-Canada” average, where the rest of Canada excludes Ontario and British Columbia.

What this benchmark is doing is converting the population of a place into an expected number of households. The expected number of households a place has will differ from the actual number of households, in part because the number of houses available in an area limits the number of households that can be formed. Housing shortages cause a reduction in household formation, a phenomenon known as household formation suppression:

Suppressed Household Formation (Definition): New households that would have been formed but are not due to a lack of attainable options. The persons who would have formed these households include, but are not limited to, many adults living with family members or roommates and individuals wishing to leave unsafe or unstable environments but cannot due to a lack of places to go.

Calculating the number of households a place should have, given the structure of its population, is, in essence, calculating the number of homes it should have. That is the essence of the RoCA Benchmark.

The RoCA Benchmark is a far from perfect tool as it makes many simplifying assumptions. Most notably, it treats all homes as the same, even though a four-bedroom home will likely house more people than a studio apartment. It doesn’t consider the cost of those homes, and the values would look somewhat different if, say, 2006 was chosen as the baseline rather than 2016. But despite these drawbacks, the tool is still quite valuable.

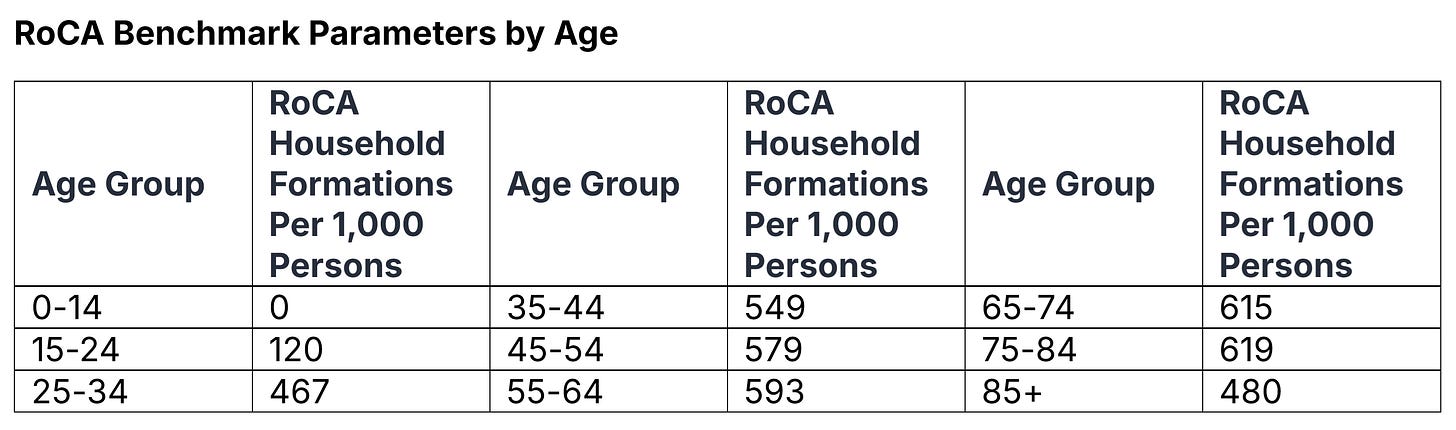

To calculate the number of homes a place should have, you sort their population by age into nine buckets, then multiply by the given factor. For example, for every 1,000 persons between the ages of 25 and 34 added to a population, the RoCA Benchmark number of households increases by 467. On the other hand, kids under the age of 16 have a factor of zero in the benchmark, as adding a child to a family typically does not increase the number of homes a place needs (though it may leave that family wanting a larger home).

The factors are as follows:

We can establish the size of housing shortages by comparing the number of RoCA Benchmark households to the number of homes. For example, by comparing population and housing data from Census 2021, we found that, in 2021, Canada had a shortfall of approximately 690,000 homes, with roughly 470,000 of that shortfall occurring in Ontario.

Estimated Housing Unit Shortfall as of 2021 by Province

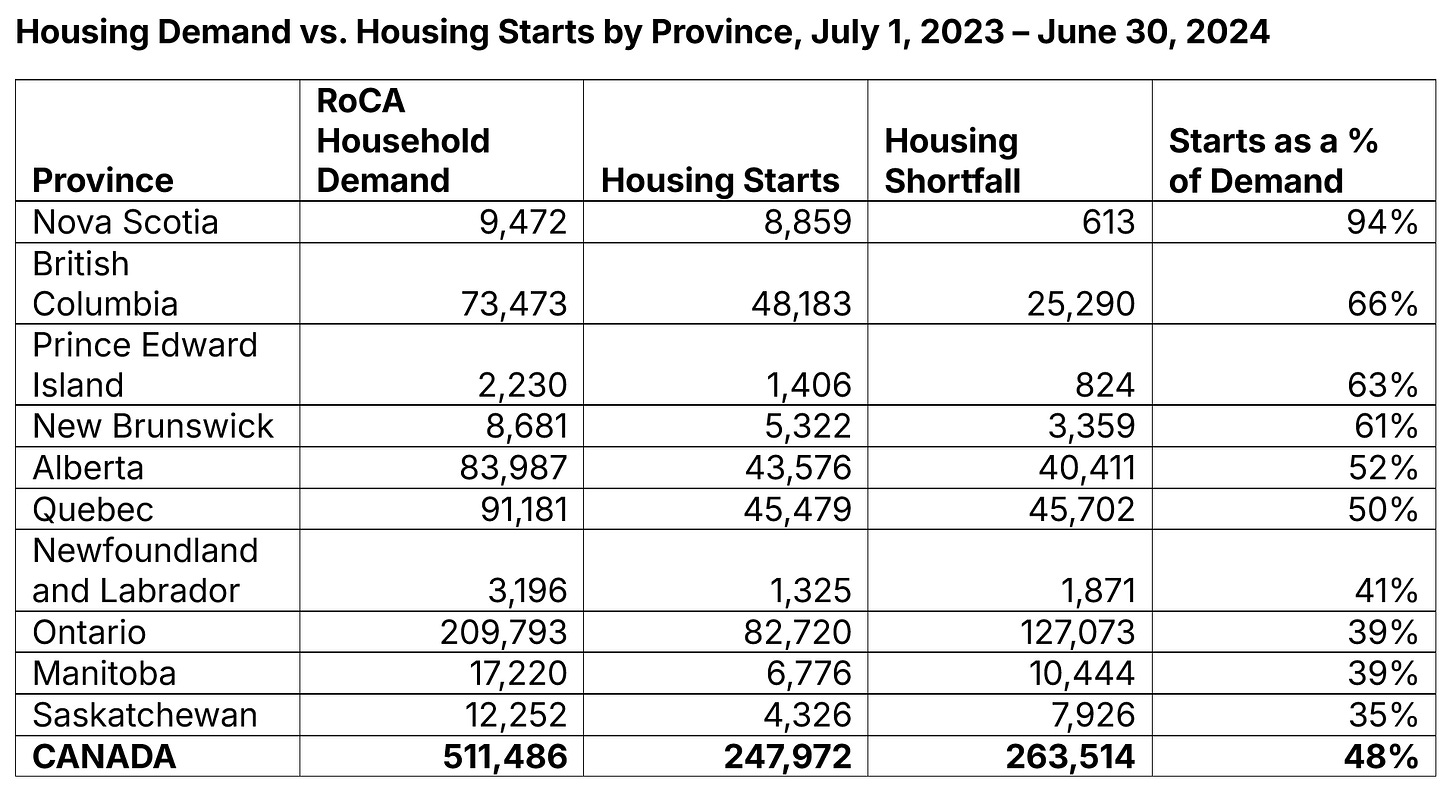

The RoCA Benchmark also allows us to determine how many houses a place would have needed to add to keep up with population growth. According to Statistics Canada’s population estimates by age and gender, Canada’s population grew by over 1.2 million people between July 1, 2023, and July 1, 2024, with Ontario adding nearly 500,000 people. Plugging this data into the RoCA formula, Canada would have needed to add over 500,000 homes, with 200,000 of those homes in Ontario.

We can then compare the RoCA Household Growth numbers to the number of homes that were built, using Statistics Canada data, to determine the year's housing supply shortfalls, with two limitations:

1. The CMHC stopped collecting full housing completion data in 2022, so we must use housing starts rather than housing completions as our metric.

2. The housing starts data excludes the territories.

Our RoCA Benchmark method finds that no province was able to keep housing starts in line with population growth. Nova Scotia’s performance was head and shoulders above the other provinces. Five provinces started less than half the houses they needed to keep up with population growth, with Ontario having the biggest housing shortfall, in absolute terms, of 127,000 units.

The disconnect between population growth and the increase in housing supply is the prime cause of the housing crisis. Population growth will be slower in future years as the federal government has made a number of changes to immigration targets and non-permanent resident programs. However, as a country, we also need to raise our homebuilding game to keep up with future population growth and account for pre-existing housing shortages.