Health Innovation Doesn’t Have to Be This Hard

Outdated rules are holding Canada back.

Highlights

Canada’s health data system is stuck in the 1990s: The 25-year-old Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), along with a maze of incompatible provincial rules, acts as a barrier to trade, making it harder to develop new treatments, run clinical trials, or use AI in healthcare.

Outdated regulations are costing us real money: Canada could save billions each year by using data more effectively, but rigid rules keep innovation slow and expensive.

Canada should avoid calls to harmonize our rules with Europe’s: Quebec has already moved in this direction with Law 25. However, Europe’s heavy-handed model slows innovation, and we risk importing their problems without fixing ours.

Canada is falling behind: Other countries are racing ahead with flexible, “agile” regulation that lets researchers safely test new technologies without drowning in red tape.

The middle class loses most when breakthroughs are delayed: Reduced innovation leads to slower access to new treatments, higher healthcare costs, and fewer high-paying jobs in biotech and health tech.

Fixing this is entirely doable: Canada can modernize our privacy laws, set national standards, and adopt smart, risk-based regulation that protects people and accelerates innovation.

The first report in the Unleashing Innovation series

This morning, we released the report Unleashing Innovation: The Case for Agile Health Data Regulation, in partnership with Canada 2020, the first in the Unleashing Innovation series. The report is available for download at the bottom of the page.

The context of the report is the push in some quarters to harmonize Canada’s rules with the European Union’s in a variety of sectors, including the life sciences.

In an October 2025 television address, Prime Minister Mark Carney pledged to double Canadian exports to non-US countries, noting that such trade diversification is necessary as “the decades-long process of an ever-closer economic relationship with the United States is over,” and Canada’s high economic ties to the United States have become a “vulnerability”.

Given the EU’s importance as an export market, its alignment with Canada on issues such as human rights and democracy, and the existence of our free trade deal with the EU (CETA), exports to the EU will play a vital role in Canadian trade diversification.

One obvious way for Canada to achieve this goal is to reduce trade barriers by adopting EU regulatory standards in key economic sectors. Canadians, after all, fully recognize that differences in provincial regulations reduce trade, and the federal government has committed to reducing intraprovincial trade barriers through regulatory harmonization. The same principles apply to international trade, and if Canada were to adopt EU standards domestically, it would reduce the cost for Canadian companies exporting goods and services to the EU.

We would caution against such an approach. The European Union’s precautionary approach to regulation often stifles innovation and has contributed to the EU’s lacklustre innovation performance and relatively modest number of tech giants. Instead, Canada should adopt a more risk-based regulatory approach and harmonize only with the EU when doing so will simultaneously enhance innovation and lower trade barriers.

We are not the first to observe that the European Union’s regulatory approach is stifling growth. The Draghi Report on EU Competitiveness highlights how the EU’s precautionary approach to regulation has led to its economic lag behind the US, and notes that only four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European. It notes that the solution is not deregulation, but rather “about ensuring the right balance between caution and innovation”. The Draghi Report also contains a blueprint for reform, with many lessons and recommendations also being applicable to Canada.

Questions surrounding regulation for innovation are at the core of MMI’s commitment to creating a Canada where every middle-class individual or family, in every city, has a high quality of life. Economic growth driven by productivity increases and the creation of innovative new products and services is necessary, though not sufficient, for creating broad-based middle-class prosperity. At the same time, Canadians also expect protection from unsafe products, exploitative practices, and environmental harm. It is vital that Canada not stifle innovation while protecting what we value most. When regulation focuses on outcomes rather than rigid processes, it can protect what matters most while opening the door to new ideas, better technologies, and faster growth.

Two paths forward for regulation

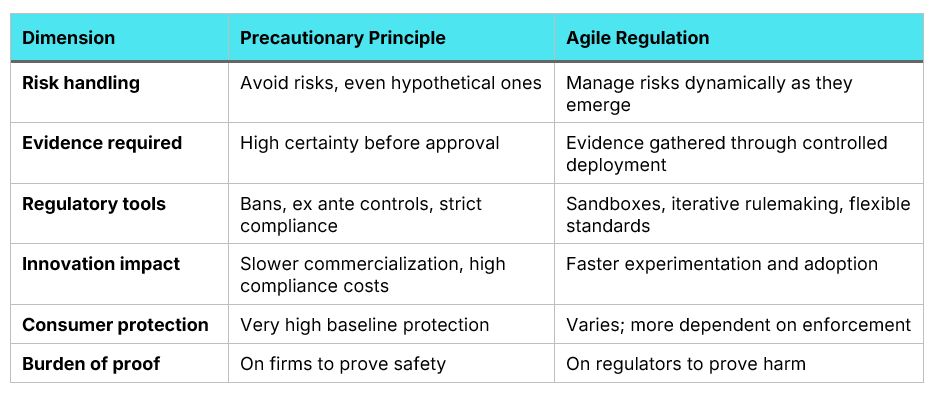

Regulatory systems across advanced economies can be thought of as existing on a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum is the precautionary principle, formally articulated in Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which requires regulators to act to address potential threats to human health or the environment even when causal relationships are not yet scientifically established. On the other side of the spectrum are a suite of agile regulatory models, designed to accommodate technological uncertainty through flexibility, experimentation, and iterative rule-making.

Path 1: The precautionary principle

Article 191 establishes the precautionary principle as a foundation of EU environmental policy, stating that Union action “shall be based on the precautionary principle” and on principles of preventive action and rectification of environmental damage at source. The precautionary principle holds that regulators should not wait for full scientific certainty before responding to risks that may be serious or irreversible. The EU approach places the burden of demonstrating safety on innovators seeking market access, rather than on regulators to show potential harm.

Europe itself is starting to realize the harms of this approach, with the Draghi Report on EU Competitiveness noting that existing EU approach “discourage[s] inventors from filing Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), hindering young companies from leveraging the Single Market” and notes that innovators must navigate a complex web, including “around 100 tech-focused laws and over 270 regulators active in digital networks”.

This regulatory framework not only stifles innovation it also causes homegrown innovators to relocate to other jurisdictions, with the Draghi report noting that of the 147 start-ups founded in Europe that went on to be valued over one billion US dollars, 40 of them would also end up relocating their headquarters out of Europe, with most heading to the United States. The impact of losing innovators is not just felt by investors, but has impacts on productivity and ultimately middle-class wages. A 2024 European Central Bank bulletin finds that over the previous five years, productivity per hour worked rose by only 0.9% in the euro area, while it increased by 6.7% in the United States. Productivity increases are a necessary (though not always sufficient) component in increasing the material well-being of a nation’s middle class.

Path 2: Agile regulation

Agile regulation represents the other side of our regulatory spectrum, emphasizing flexibility, proportionality, and learning-by-doing. Rather than imposing comprehensive controls up front, agile systems employ adaptive governance tools such as regulatory sandboxes, pilot programs, iterative guidance, and risk-based oversight to create space for experimentation while maintaining appropriate safeguards.

Examples of this approach exist worldwide. For example, the UK’s 2023 Pro-Innovation Regulation of Digital Technologies Framework articulates a model in which regulators are encouraged to support responsible experimentation, engage early with innovators, and adjust rules as evidence accumulates. Regulatory sandboxes, first pioneered by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, allow firms to test new products under regulatory supervision with waivers from certain rules, facilitating innovation in areas such as fintech and digital health.

Figure 1 outlines the differences between the two ends of our regulatory spectrum.

Figure 1: Precautionary Principle vs. Agile Regulation

Agile regulations, however, require government institutions built for that purpose and to course-correct if needed. In a 2021 report on the energy sector, Kaiser, McCarney, and Elgie find that institutions are vital but often overlooked:

We argue that increasing regulatory agility, in practice, relies heavily on the regulatory institutions, which implement regulations and define the practice of regulatory management... There are multiple characteristics of regulatory institutions that enable regulators to operate in a more agile manner (e.g., being transparent, dynamically predictable, anticipatory, experimental, connected, adaptive)…

For example, more anticipatory approaches to regulation will require regulators to undertake direct research activities, like the production of periodic ‘foresight reports’ to understand the drawbacks and opportunities of emerging technologies and business models, in addition to foreseeing disruption with existing regulatory regimes. This kind of work, by definition, means regulators will have to be more inclusionary, working with policymakers, innovators, and experts.

Canada needs regulatory reform for health data. The economic opportunities are substantial, and the 25-year-old PIPEDA is well past its best-before date. Because Canada’s rules are so outdated and the need for reform is so urgent, there will be a temptation to adopt rules designed by our trading partners as a shortcut. We would advise against such an approach. Canada cannot afford short-run harmonization at the expense of long-run innovation.

Download the full report below