How We Think About and Measure Organizational Success at MMI

What we track, what we don’t, and why it matters

Highlights

Readers really want to know how think tanks work: Not just the policy ideas, but the messy mechanics of funding, strategy, and impact behind the scenes. Specifically, they want to know “What does success look like for a think-tank, and how does it know it’s making a difference?”

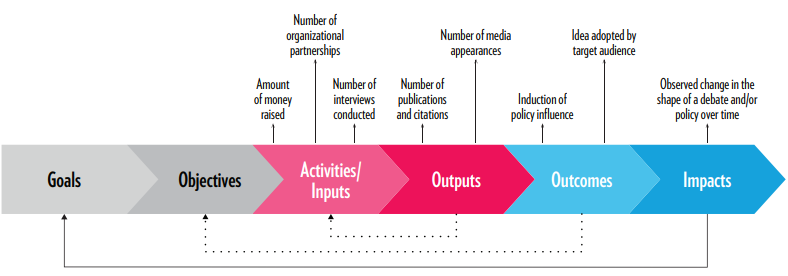

MMI adopts a linear theory of change model to define and measure success: There are six key elements to track: Goals, Objectives, Activities/Inputs, Outputs, Outcomes, and Impacts.

There are many traps that think-tanks can fall into: Traps include failing to have a well-defined goal, mistaking an objective for a goal, underfocusing, or overfocusing on input metrics such as fundraising.

Measuring think-tank success is hardest where it matters most: The most important impacts, real policy change and lived outcomes, are the least measurable and hardest to attribute to the actions of the think-tank.

Outputs are not impact: Reports, media hits, downloads, and subscribers matter, but maximizing traffic is not the same as changing outcomes.

The surprising interest in how the sausage is made

The Missing Middle Initiative has been in existence for less than a year, and we get a lot of questions via email and comments on our YouTube channel. One thing I had not expected was how many of you would be interested in the mechanics of starting and running a think-tank. Today, we’re going to answer one of those questions.

In general, when it comes to questions about think-tanks and MMI itself, two broad types are more common than the rest:

What do policy think-tanks actually do?

What does success look like for a think-tank, and how does it know it’s making a difference?

We covered the first question in our Missing Middle podcast episode Think Tanks Explained: How They Shape Policy (and Pay the Bills), which I highly recommend to anyone who wants to know how the sausage is made.

The second question is far trickier, but it is vitally important for anyone running, or thinking about starting, a policy think-tank. The challenge is that, in the think-tank performance world, there is an inverse correlation between ease of measurement (and attribution) and importance. That is, the things that are straightforward to measure tend to be less important, and the things that are of the utmost importance are hard to measure, or even attribute to the actions of the think-tank.

The disconnect between measurability and significance often leads think-tanks to ignore the question entirely or answer it superficially if it is required for a grant application. As someone who has spent nearly two decades in the think-tank space, I understand the instinct to avoid measuring impact, but I advise against adopting such a mindset. Instead, think-tanks should do their best and recognize the value of even partial, incomplete data.

I did not arrive at this opinion solely on the basis of my own experience. Our thinking at MMI on the issue has been heavily influenced by a few resources, which I have listed below, as this piece refers quite extensively to them:

The 2023 study Whose Bright Idea Was That? How Think Tanks Measure Their Effectiveness and Impact (free PDF available at the link) by Sarah Bressan and Wade Hoxtell. At 80 pages, it is quite detailed and highly recommended for anyone considering starting or working for a think-tank.

The 2013 CIGI blog post by Fred Kuntz, titled, Communications and Impact Metrics for Think Tanks. The 15 metrics are particularly helpful, as well as the emphasis on the attribution problem: “A think tank may say it put forward an idea, but if others had the same idea, who gets the credit if a policy is implemented?”

A 2016 post by Dena Lomofsky: Monitoring, evaluation and learning for think tanks. It provides a useful second opinion to the CIGI blog.

The book Northern Lights: Exploring Canada’s Think Tank Landscape by Western University Political Science Prof Don Abelson. The Canadian think-tank space is incredibly underdeveloped relative to our G20 peers, and Abelson’s 2016 book is the only one that I know of that examines think-tanks from an explicitly Canadian perspective.

Here is how we navigate thinking about, and measuring, effectiveness and impact at MMI.

From Goals to Impact

The Bressan and Hoxtell book contains several models for mapping how think-tanks create change. Although in my experience, creating policy change is a highly non-linear iterative process, I find Bressan and Hoxtell’s linear model far more useful than the more complex non-linear models detailed in their book.

I particularly like their linear theory of change, as it’s one of the few that I have seen that explicit maps goals and objectives to outcomes and impacts, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Linear Theory of Change Model with Linear Indicators

Source: Whose Bright Idea Was That? How Think Tanks Measure Their Effectiveness and Impact

I’ll use MMI as an example of how think-tanks think about these six components of a theory of change, and note areas where MMI deviates from conventional wisdom.

Goals

The biggest single mistake I see new think-tanks make is failing to think through what they are trying to accomplish, and instead defining themself by an area of focus, e.g. “we’re a think-tank that studies transportation,” rather than a vision. This inevitably leads the organization to release a series of disconnected research pieces that are often contradictory. The failure to have an explicit, well-thought-out goal also leads to poor policy design, as the think-tank has difficulty determining what it is trying to optimize for and is often unable to distinguish between an objective and a constraint.

To avoid this trap, we highly recommend adopting Rich Horwath’s GOST framework, which links goals, objectives, strategies, and tactics, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GOST Framework Element Definitions

Source: Whose Bright Idea Was That? How Think Tanks Measure Their Effectiveness and Impact

A related mistake we see from think-tanks is failing to distinguish between goals and objectives, which often leads them to define an objective as the goal. A goal should be something broad and long-range, and is often (but not always) qualitative. Goals for policy think-tanks should be able to be expressed in the form of a statement like the following:

Eliminate child poverty in Ontario.

Boost Canada’s standard of living by becoming the most innovative country in the world.

Eliminate homelessness in Winnipeg in the next ten years.

Instead, think-tanks often fall into the trap of setting an objective as a goal. Often, that hybrid objective-goal is the enactment of a single policy reform, for policy’s sake, such as “have Canada institute a universal basic income” or “implement a land-value tax in New Brunswick.” These specific policy reforms are all perfectly reasonable objectives, but without an end goal in mind, they are hard to design well. A universal basic income intended to eliminate poverty will look different from one intended to accelerate innovation, or from one designed to reduce the size of the public service. Furthermore, unlike goals, objectives should change over time as circumstances and research evolve. The think-tank may discover that a universal basic income is not the most effective way to eliminate poverty, in which case their work should pivot. But if they define their goal as a universal basic income, pivoting is not an option.

In other words, a goal should be a North Star that guides the think-tank’s work, while an objective guides the work toward that goal. Or, more simply, the objective is the means, the goal is the end.

Our goal at MMI is as follows:

A Canada where every middle-class individual or family, in every city, has a high-quality of life and access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options that are affordable, adequate, suitable, resilient, and climate-friendly.

There are a handful of design choices when setting out a goal, which are apparent in the goal we have set for MMI:

The goal should carve out a niche for the organization. A think-tank should not attempt to solve all of the world’s problems. Instead, it should create a sandbox that addresses a specific set of problems. This guides the types of work we should and should not take on and allows us to specialize. For MMI, we made the explicit choice to limit ourselves to the middle class in Canada. Other great think-tanks are looking at anti-poverty issues, or those that consider middle-class issues in other countries. We don’t need to compete with them. Instead, we carved out an important issue that we can own.

The goal should clearly indicate the organization’s values. Each word in our goal serves a purpose and sends a clear signal, both within and outside the organization, of how we view the world. In our goal:

There is a clear emphasis on choice. Middle-class families should be able to live where they want, how they want, and both homeownership and rental should be attainable options.

Our conception of well-being is more broad than income, wealth, and the economy. We explicitly focus on quality of life, which we define here.

We recognize that housing is a primary, but not sole, issue for the middle-class, and that while affordability is necessary for a well-functioning middle-class housing system, it is not sufficient. Housing must also be adequate, suitable, and aligned with Canada’s environmental and climate goals.

The goal statement (or statements) for each think-tank will differ, but they should clearly identify what the think-tank is trying to accomplish and the values that it holds as non-negotiable.

Objectives

The objective statement or set of objectives lays out how the goal will be achieved. Many organizations like to lay out annual objectives with quantifiable targets. At MMI, we have chosen to forgo a target, but we have a goal we can measure annually.

Objective: To have governments across Canada, as well as government-related entities from crown corporations to regulatory bodies, enact evidence-based reforms that move Canada closer to the goal identified by MMI.

The choice to set a quantifiable target in an objective is a matter of personal preference; we have chosen to forego one because it is unclear to us what a reasonable target would be. Circumstances will often dictate whether to adopt explicit targets for an objective.

Activities and Inputs

Activities and inputs include metrics such as the amount of money raised, the number of funders, and the number of stakeholder meetings. It is not the number of reports issued or events held; that’s in the next section. Rather, it is the work that goes into the outputs.

The most existential metric in this section is funding. There are two traps that think-tanks can fall into. The first is neglecting the business development aspect of running a think-tank and instead focusing on producing the highest-quality work possible. While admirable, if you don’t raise enough money to keep the lights on, your think-tank will have a short shelf-life.

The other trap is going too far in the other direction and hyperfocusing on growing revenues. Think tanks lose their way when they take on projects that fall outside their goals and objectives. Even when the funding received is for work within the organization’s mandate, think-tanks can grow too quickly, which impairs their ability to do good work. Empire-building can kill a think-tank almost as quickly as an inability to pay the bills.

In general, we believe that think-tanks should set a minimum and a maximum revenue target for a year (in 2026, ours is $1.1-$1.4 million), where possible, obtain multi-year funding to create certain, and rely on a larger number of supporting partners who provide smaller funding amounts, rather than relying on a couple of large funders. While working with one or two funders is much less work, it puts the organization at risk should a funder not renew and can harm editorial independence, as it is harder to say “no” to a funder whose support the organization is reliant.

Think tanks use many different metrics to assess inputs and activities. The Kuntz paper lists the following three “resource metrics” that think-tanks often use; note that Kuntz highlights the diversity and stability of funding as critical.

Quality, diversity and stability of funding.

Number, experience, skills, reputation of experts, analysts and researchers.

Quality and extent of networks and partnerships.

The Bressan and Hoxtell book provides two qualitative and nine quantitative input metrics, which they categorize as “organizational metrics.” They include measures such as employee retention rates, as well as fundraising metrics such as “number of donors and/or financial or in-kind contributions,” “amount of money fundraised,” and “number of grants or tenders won.”

In general, MMI spends less time on input metrics and more time on output metrics.

Outputs

Outputs are the things the think-tank actually does, or third-party references to the work produced by the think-tank. These are reports, media interviews, and the case of MMI Substack posts and podcast episodes. What gets tracked is not just the number of pieces of content or the number of media interviews, but how well that content performs or how many people saw that interview.

Our output metrics differ from most traditional think tanks because we employ a different knowledge mobilization strategy. Most think tanks tend to release a small number of large reports each year, with mobilization tactics centred around each release, a “few and big” strategy. MMI employs the opposite strategy, focusing on “small, fast, and frequent” releases. MMI publishes content multiple times a week across our Substack podcast and opinion pieces in third-party outlets, as well as a handful of larger pieces throughout the year. Our goal is to mobilize the knowledge we have generated and ensure it reaches policymakers, media, industry, academics, and the public.

Tracking these numbers is vital, but the trap that think-tanks can fall into is treating maximizing their output metrics as their ultimate goal. Having more YouTube subscribers, for example, can help us achieve our goal, but it is not the goal. Often, releasing a video on an important topic watched by fewer people is more impactful than releasing something trivial that is widely seen. In short, it is vital to track output metrics and be aware of what they tell you, but the goal should never be to maximize traffic.

The Kuntz paper provides nine important output metrics, which they have divided into “exposure metrics” and “demand metrics.” Not all of these will be applicable in every situation; a think-tank that does not produce academic-style research will typically not be overly concerned with scholarly citations.

Exposure metrics

Media mentions.

Number and type of publications.

Scholarly citations.

Government citations.

Think tank ratings.

Demand metrics

Events. The number of conferences, lectures and workshops, and the number of attendees.

Digital traffic and engagement. Number of website visitors, page views, time spent on pages, “likes” or followers.

Official access. Number of consultations with officials, as requested by the officials themselves.

Publications sold or downloaded from websites. This is not the measure of output, but rather the external “pull” on the publications.

Traditionally, MMI does not track “official access” because we never want officials to feel that we’re meeting with them to maximize a metric or, worse, to use the fact that we meet with policymakers as a fundraising tool. This is my personal preference, and it may be something we revisit in the future, but in general, it is outside my comfort zone.

Bressan and Hoxtell provide dozens of additional metrics in this area that a think-tank could rely on if so inclined.

Outcomes

Policy-oriented think tanks are strange beasts. They are not lobbying shops, nor do they engage in traditional government relations. However, they also don’t release policy reports for the sake of releasing policy reports. The policy think-tank has an ultimate goal in mind, and that goal requires enacting evidence-based policy. As such, policy reforms are necessary (but not sufficient) for the think-tank to be considered a success.

The biggest challenge in tracking outcomes is what Kuntz describes as the “attribution problem”:

The problem is one of attribution — who gets the credit for a policy that is implemented? Policy input comes from many places. Public or governmental policy development is a complex and iterative process in which policy ideas are researched, analyzed, discussed and refined — often through broad consultations with many stakeholders. When a policy is finally adopted, it may wear the fingerprints of many hands. For these reasons, a think tank cannot always claim success and say, “this policy was our idea.” In many cases, it would be highly unusual for a political leader to give credit to a particular think tank for a specific policy; such leaders must take ownership of their own policies, to be accountable for them.

For example, MMI’s predecessor, the PLACE Centre, was instrumental in the creation of the National Housing Accord (NHA), a set of rental housing policy recommendations to the federal government. We held several meetings with high-ranking federal officials, and I presented some of the ideas at a federal government cabinet retreat. A few weeks after the NHA was released, the federal government adopted several recommendations, including the elimination of the GST on purpose-built rental construction.

It is unlikely that all, or even most, of those reforms happen without the NHA. But proving that they wouldn’t have happened without the NHA is impossible. Furthermore, many of the recommendations in the NHA were not novel; they had existed for some time. For example, eliminating GST on purpose-built rental construction was an unimplemented idea from the 2015 Liberal campaign platform. It is unclear how much credit we can give to the NHA or its authors for the federal government’s implementation of NHA-based recommendations. And when new policies are released, multiple groups will take credit, most of whom have a very strong case. As JFK remarked, “victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan.”

Because of the attribution problem, many think-tanks prefer not to attempt to track outcomes. Given the importance of outcomes, we believe they should be tracked, while recognizing the limitations of those metrics.

Kuntz highlights three impact and quality-of-work metrics as particularly important.

Policy Impact and Quality of Work

Policy recommendations considered or actually adopted.

Testimonials.

Quality of the think tank’s work.

Impact

This is the most important part of the linear change model, and ironically, the one that is least likely to be measured.

Let’s say you’re a think-tank devoted to housing affordability, and your policy recommendation to “allow fourplexes as-of-right anywhere in the city” gets adopted by a municipal government.

There are a number of post-implementation measures that should be tracked, such as:

Were more fourplexes built in the community relative to similar communities where the policy was not adopted?

If so, did the increase in fourplexes lead to improved outcomes, such as lower home prices and rents, higher vacancy rates, higher rates of intraprovincial migration, higher homeownership rates, lower rates of homelessness, etc., than similar communities that did not make the change?

Unfortunately, it is rare for think-tanks to conduct this type of assessment. It is not due to a lack of interest on the part of the think-tank; it is because this type of research is expensive, and there is a lack of interest among funders. It is the type of project that governments themselves should fund; they should want to know whether the reforms they enacted actually accomplished anything. In practice, most governments would rather look forward, to the next policy challenge, than look back at previous reforms, so this type of funding is nearly impossible to obtain.

It is the type of research that MMI would love to conduct; a lack of interest prevents us from doing so.

And that is how the sausage is made

We hope that answers your questions on what success looks like for a think-tank and how do we know we’re making a difference. I suspect, despite the length of the piece, it may have created additional questions. If so, please send them our way. We’d love to hear from you!