The Policy Sleight of Hand Behind “Growth Should Pay for Growth”

Houses don't use libraries, people do

Highlights

High and rising development charges are defended on the grounds that “growth should pay for growth”.

While a powerful rhetorical shield, the phrase “growth should pay for growth” relies on the polysemous nature of the word “growth,” leaving it unclear whether the initial use of the term refers to population growth, housing supply growth, or something else. This vagueness makes it a powerful but misleading justification for high development charges.

Development charges are framed as necessary to cover community infrastructure, such as libraries, parks, and arenas; however, population growth, rather than housing, creates the demand for these services.

Treating housing growth as a proxy for population growth is reasonable in some places and times, such as environments where population growth comes primarily from local sources; today, Ontario’s growth is overwhelmingly due to migration, especially international arrivals, not local household formation.

Infrastructure needs stem from population growth, which is driven by policy. The benefits of population growth through immigration to our labour market, our economy, and our social fabric are widely distributed.

However, using development charges to pay for the required infrastructure to support this population growth disproportionately places the costs on new homebuyers and renters, including the newcomers themselves.

“Growth should pay for growth” is a political choice to socialize the benefits of immigration while privatizing its infrastructure costs onto younger cohorts, insulating established homeowners and corporations from financial responsibility.

‘Cause you know sometimes words have two meanings

There is a core belief, expressed almost as a mantra, in any defence of high (and rising) development charges in British Columbia and Ontario: growth should pay for growth.

While a rhetorically powerful device, the phrase is intentionally left vague, which helps obscure the implications of that mantra. “Growth” is an abstract, uncountable noun, and linguistically is a polysemous word with many different, but related, meanings. It is typically used in reference to the growth of some other noun, like “employment growth” or “the growth of Mike’s hair”. But those noun adjuncts (employment, hair) are left absent from the phrase “growth should pay for growth”.

Or to put it more plainly, in the form of a question, “the growth of what should pay for the growth of what, exactly?”

The Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), in an explainer piece about development charges, provides one answer to the question:

Development charges (also called capital cost charges, infrastructure charges or offsite levies) are collected as part of the approval process for a new development. They can apply to many different kinds of developments – residential, commercial, industrial and institutional. They are typically levied to cover some or all of the growth-related infrastructure costs resulting from the new development, such as water and sewage services, roads, street lights, parks, community facilities and libraries.

These charges help ensure developers, rather than existing taxpayers, pay for the infrastructure costs triggered by development. In addition, development charges are increasingly being used to support planning goals by providing incentives (and disincentives) for certain types of development and growth.

We would disagree with much of this framing. Although true from a legal perspective that developers pay development charges, in reality, these costs are passed along to homebuyers and renters, many of whom are already “existing taxpayers”.

But, for this piece, we can adopt CUPE’s description of development charges to amend our phrase, in the context of residential development charges, to:

“The growth of the housing supply should pay for the growth in infrastructure like community facilities, libraries, and arenas.”

But, in this formulation, figurative cracks in the logic of the expression begin to appear:

Condos don’t use community facilities.

A duplex has never checked a book out of the library.

I’ve played in my fair share of beer league games, and I’ve never seen a townhouse lace up the skates.

I can already hear the obvious retort, “Don’t be daft, of course the structures don’t use those resources, but the residents do!”

But do they use them more than they would without the house?

It makes me wonder

For example, in the early 2000s, I was living with my parents in London, Ontario, saving up for a house. In 2004, my partner and I bought this newly built home in London, ON, for $168,000:

Figure 1: Mike’s former house

Source: LSTAR

Back then, the development charges were around $5,000 ($7,800 in today’s money), which the developer included (with markup) in the final price of the home. For a new home today, they would be $48,526, an increase of 870% in nominal terms, or 522% after accounting for inflation.

These charges, and their rapid growth, are often defended on equity grounds, including in the first paragraph of the report Development Charges in Ontario: Is Growth Paying for Growth?:

The principles of efficiency, equity, and accountability in government underlie many policy positions, including the prescription that municipal services should be paid for by those who benefit from or otherwise create the need for the services. A growing municipality is expected to recover growth-related operating and capital costs from the new developments that give rise to them, although this recovery occurs in various ways across municipalities in terms of the mix of revenue tools and methods employed.

But the building of the home, and my being able to move out of my parents’ home, did not give rise to additional expenses:

Moving to this home did not increase my library usage.

Moving to this home did not increase my use of local parks and facilities.

Moving to this home did not increase my use of roads in the city. In fact, my driving was significantly reduced because I was able to purchase a home closer to where I worked. High road usage is typically a sign of a lack of development, forcing people into long commutes.

It did, however, turn my partner and me into property taxpayers, which helps fund the maintenance of those libraries, parks, and roads.

Of course, there were new pieces of infrastructure that needed to be built to support this house. The roads in the subdivision, the sidewalks, the sewers and the lamp posts. However, development charges paid for none of those; the developer (not the city) pays for the construction of those outside of the development charge system, and passes those costs along (with a markup) to the homebuyer. Annual property tax payments pay for their upkeep.

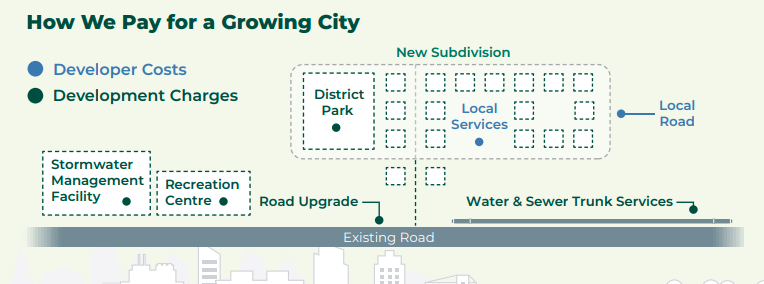

Figure 2: Developer Costs vs. Development Charges

Source: City of London.

The power behind the rhetorical device of the phrase “growth should pay for growth” stems from its not forcing a distinction between population growth and housing supply growth, allowing them to be interchangeable.

While the two are never fully interchangeable, there are scenarios where one is a reasonable proxy for the other. For example, while it is true that my partner and I didn’t use any more roads, libraries, or arenas than we did before, we did eventually have children, and they use municipal libraries. We drive them on municipal roads to go to municipal arenas.

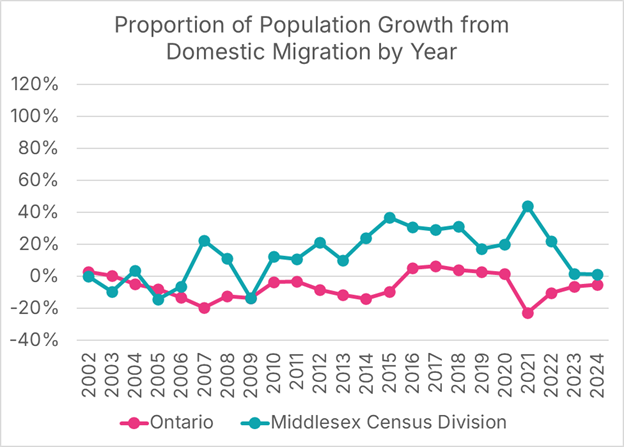

In a place and time where population growth primarily comes from young people moving out, buying or renting a home, and then having children, housing growth is a reasonable proxy for population growth. We do not live in that time; our population growth is increasingly driven by migration. Particularly at the local level, a significant portion of this is due to domestic migration; London (in Middlesex Census Division) has seen an influx of new residents from the GTA.

Figure 3: Proportion of Population Growth from Domestic Migration by Year

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0153-01, Chart Source: MMI.

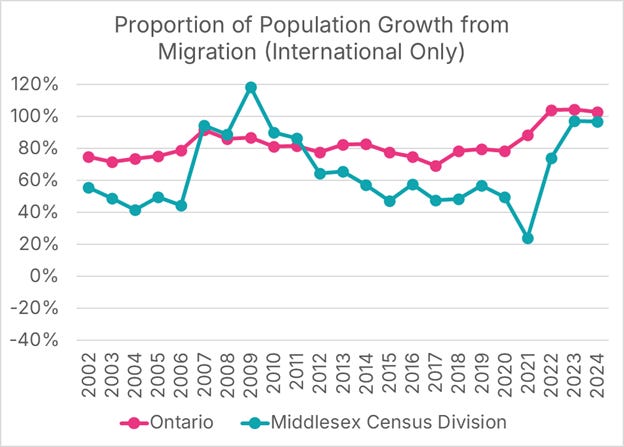

However, the vast majority of population growth originates from international sources, including both permanent residency (immigration) and non-permanent resident programs, such as temporary foreign workers and international students. In Ontario, international migration has accounted for over 70% of all population growth every year since 2002, exceeding 100% in each of the last three years.

Figure 4: Proportion of Population Growth from International Migration by Year

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0153-01, Chart Source: MMI.

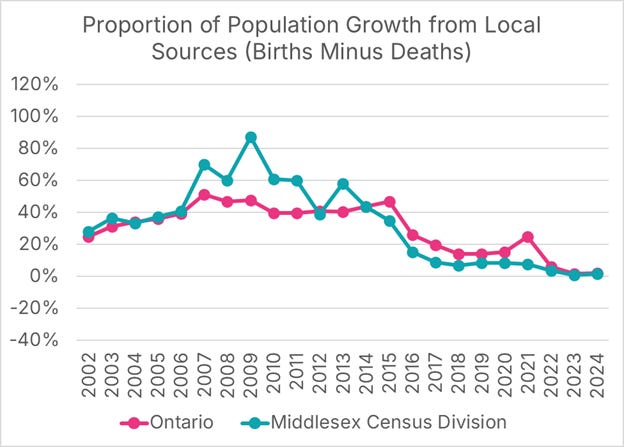

Only once this century has local growth (births minus deaths) accounted for over half of all net population growth in Ontario; currently, in both Ontario and the Middlesex Census Division, it accounts for only 2% of all net population growth.

Figure 5: Proportion of Population Growth from International Migration by Year

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0153-01, Chart Source: MMI.

In short, it isn’t homes that create the need for infrastructure, it is population growth. And that population growth isn’t being caused by young people buying homes; it is a function of population growth policies like immigration and the temporary foreign worker program, a fact that the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) understands very well:

Ontario’s municipal governments are welcoming communities. Although immigration is a shared federal and provincial responsibility, immigrants and refugee claimants interact with municipal services such as emergency shelters, housing supports, recreation, cultural, transit, public health, employment programs and other social services almost immediately upon arrival. Many municipal governments also actively undertake efforts with dedicated resources to attract new immigrants to their communities. For example, many communities with post-secondary institutions have an interest in encouraging international students to apply for permanent residence. We are proud of the role we play in helping to attract, settle and integrate newcomers into our towns, villages and our cities…

Immigration is vital to address labour market shortages and to advance local economic development in our communities. Newcomers also enrichen our social fabric.

We absolutely agree with AMO on the benefits of immigration and the benefits of having international students. I was an international student in two different countries (the Netherlands and the United States), and I believe the experience was beneficial for both me and the host country.

We also absolutely agree with AMO that population growth also causes the need for infrastructure, and that population growth is policy-driven. Although the benefits of immigration to our labour market, our economy, and our social fabric are widely distributed, the up-front infrastructure costs are not widely shared, but rather placed on a small subset of new homebuyers and renters, including the newcomers themselves.

We need to have an honest discussion about how fast Canada’s population should grow, who benefits from that growth, and who should bear the infrastructure costs associated with that growth. The linguistically vague rhetorical shield of “growth should pay for growth” avoids that conversation and allows for population growth-related expenses to be disproportionately placed on the young.