What Happened to the Young Middle-Class Man?

Canadian men under 45 earn less than their 1970s counterparts, even as seniors hit historic highs, and homeownership trends make the gap even wider.

Highlights

A generational flip no one saw coming: For the first time in recorded Canadian history, the average 65-year-old man now earns more than the average 25–34-year-old man.

Younger men are going backward: After inflation, average incomes for men aged 25–34 have fallen by $8,300 since 1976, and median incomes have dropped even further, by $14,300.

Older men are surging ahead: Men 65+ have seen their average after-tax incomes rise by $26,000 over the same period, thanks to stronger pensions, higher investment income, and more generous government transfers.

Employment income tells the real story: Young men earn $6,500 less in employment income than their counterparts did nearly 50 years ago, and the share of young men with any employment income has also fallen.

Seniors’ gains come from working more and saving more: Older men now work later into life, boosting employment income, while investment and retirement income have more than doubled since 1976, and government transfers have become far more generous.

And none of this includes home equity, where the generational gaps are even wider: Rising home prices have enriched older, home-owning men while disadvantaging younger men who have not yet entered the market.

Things are not getting better

A recent article in Esquire Magazine, with the headline, How Do Young Men See the World? We Asked Them painted a picture of stagnant (or worse) economic outcomes for men in the United States and how that affected their self-perception and views of society.

If we had the budget of Esquire, we would conduct similar interviews to see if the same held in Canada. But we don’t. Instead, we looked at how men’s earnings have changed over time to provide insights into the progress young men have (or haven’t) made over the last few decades.

In a future piece, we will examine economic outcomes for women.

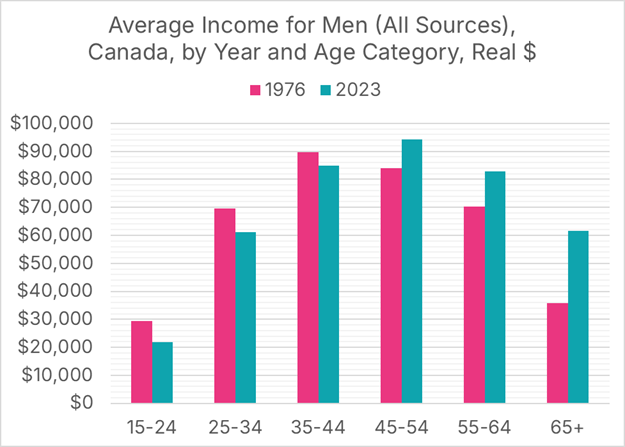

Statistics Canada’s Canadian Income Survey is a useful place to start. The Survey’s Table 11-10-0239-01 contains after-tax, real (inflation-adjusted) incomes for men by age category, spanning the years 1976 through 2023. Men under the age of 45 are, on average, earning less after inflation than their counterparts did in 1976, while those 45 and older are earning more. Seniors, in particular, have experienced a large increase in average incomes since 1976.

Figure 1: Average income for men, from all sources, Canada, by year and age category, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars.

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

In 1977, the average 25-34 year old man earned over twice that of a man aged 65+. In 2023, for the first time in recorded history, senior men now earn more, on average, than their 25-34 year old counterparts.

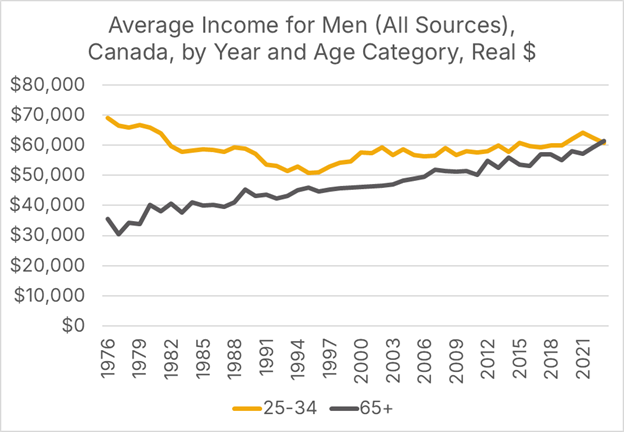

Figure 2: Average income for men, from all sources, Canada, by year and age category, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars.

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

Averages, however, do not necessarily reflect the experience of a typical person in a group. On average, Bill Gates and I are billionaires, and Wayne Gretzky, Alex Ovechkin, and I have, on average, scored over 600 NHL goals.

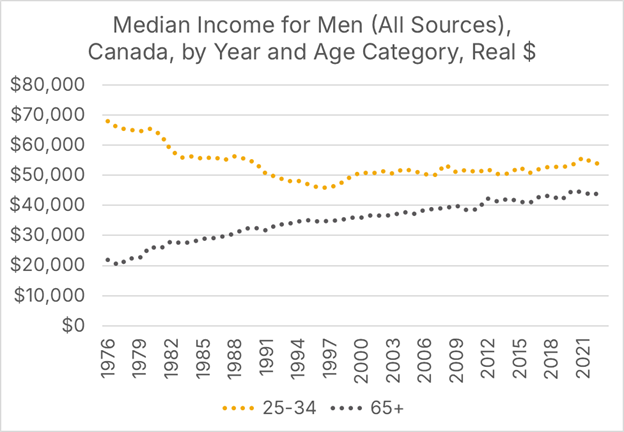

It may be that a cohort of very high earners is affecting the averages. We can account for this by examining median incomes instead. While the median 25-34 year old man still earns more than his 65+ year old counterpart, the data series shows a similar pattern of continually increasing income for seniors, while earnings for younger men dropped substantially in the 1970s and 1980s, and never fully recovered.

Figure 3: Median income for men, from all sources, Canada, by year and age category, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars.

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

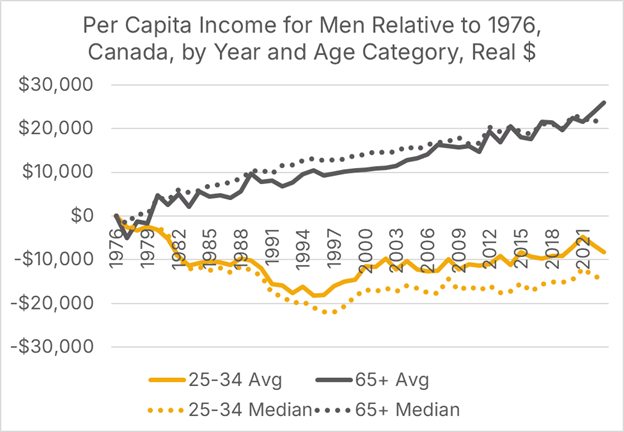

A graph of changes in income, rather than absolute levels, shows similar patterns for both median and average incomes. Both average and median incomes for older men have increased by over $23,000 since 1976, while for younger men, they have each decreased by over $8,000.

Figure 4: Per capita income for men, from all sources, Canada, by year and age category, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars, relative to 1976

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

To get a better sense of why this happened, we can divide income into the following three categories:

Employment income, which includes wages, salaries, commissions, and self-employment income.

Investment, retirement, and other income.

Government transfers, which include, but are not limited to, Old Age Security (OAS), Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), Canada Pension Plan (CPP), Child Benefits, Employment Insurance (EI) benefits, social assistance, and COVID-19 benefits.

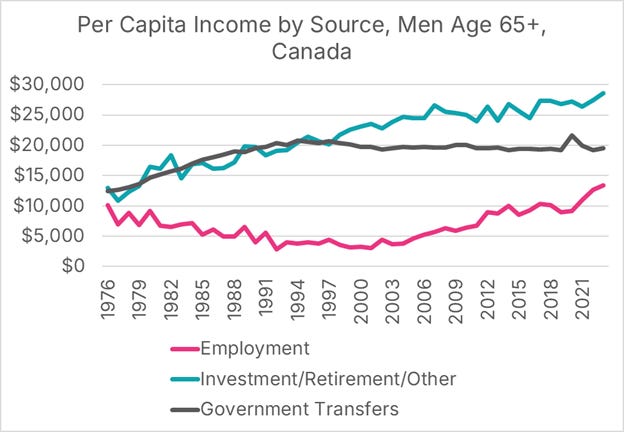

Figure 5 provides a time series of how these sources of income have changed over time for men aged 65+. We would summarize the data as follows:

Employment income for this group fell between 1976 and 2000, then rose considerably since then and is $6,400 higher today than in 1976.

Investment and retirement income has steadily increased and is now more than double what it was in 1976, up $17,600 after inflation.

Government transfers increased substantially until the late 1980s, have been steady since then, and were $7,000 higher in 2023 than in 1976.

And we should keep in mind that this measurement does not include earnings that are not treated as capital gains, such as the sale of primary residences. As such, the net worth for this group has risen considerably in ways that are not captured by income calculations.

Figure 5: Per capita (average) income for men age 65+, Canada, by year and source, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

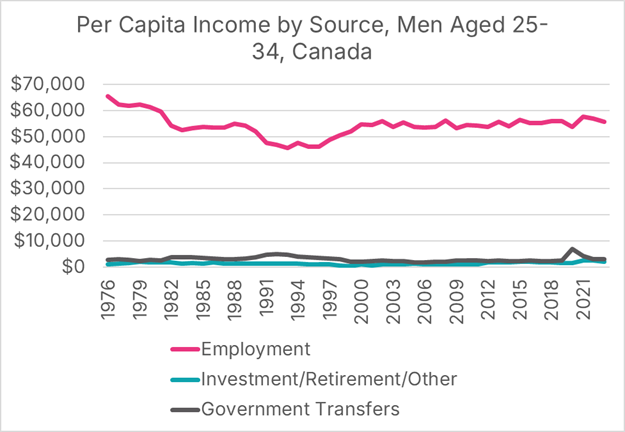

The time series for men between the ages of 25 and 34 looks substantially different, as over 90% of their income comes from employment.

Figure 6: Per capita (average) income for men age 25-34, Canada, by year and source, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

Employment income for this group has been flat since 2000 and was $6,500 lower in 2023 than in 1976, after inflation.

Investment and retirement income in real terms has nearly doubled for this group, but that has only added $750 to their annual income, as they earn little investment income.

Government transfers increased by $6, after inflation, from 1976 to 2023. Not $6,000 or $600, or $6 per year. $6 in total.

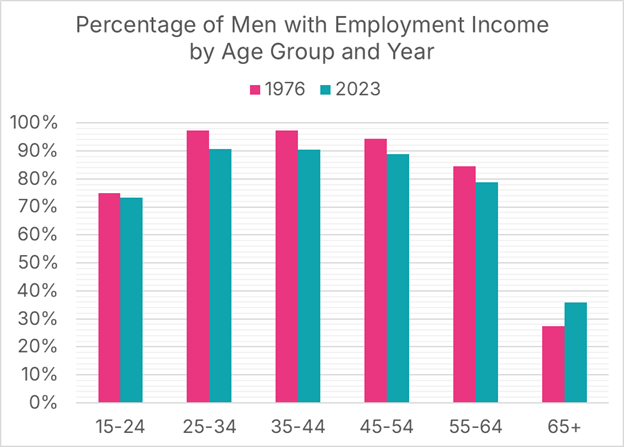

This $6,500 drop in average employment income does not mean that the average employed person between the ages of 25-34 earns $6,500 less than in 1976, because there has also been a drop in the proportion of this group earning employment income, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Percentage of men earning employment income, Canada, by age group and year, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

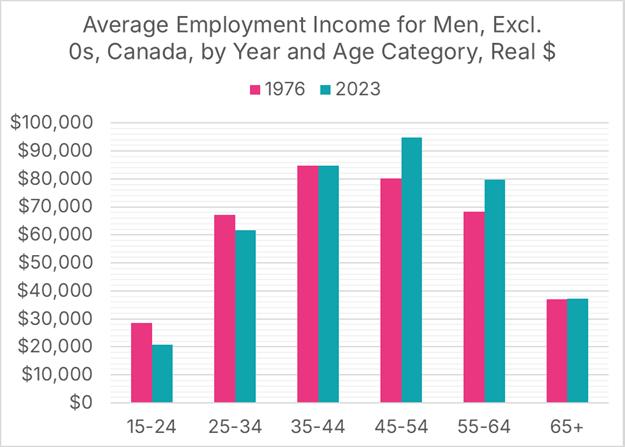

If we remove every person who earned zero employment income from our calculation, we find that average employment income for 25-34-year-olds dropped by $5,600 rather than $6,500. Average employment for senior men is now flat since 1976 once the non-employed are removed from the calculation, which shows that the employment income gains for senior men since 1976 have come from more senior men working, rather than from wage increases.

Figure 8: Average employment income for men, excluding men with $0 in employment income, Canada, by age group and year, in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 11-10-0239-01, Chart Source: MMI.

In short, incomes have been stagnant or declining for young men since 1976, though there is significant nuance in the numbers.

Summary of the last 45 years of men’s earnings

For the first time in recorded history, the average 65-year-old man earns more than the average 25-34-year-old.

Average real (inflation-adjusted) incomes have fallen by $8,300 for men between the ages of 25-34, and median incomes have fallen by $14,300. For 65+ year old men, they have risen by $26,000 and $23,100, respectively.

For older men, the biggest rise in income is due to increased government transfers, such as CPP and GIS/OAS, with most of these gains occurring in the 1970s and 1980s. Increased investment income and pension savings are also significant contributors. Older men are also, on average, earning more employment income, though this is largely due to a higher proportion of senior men continuing to earn employment income after age 65.

For younger men, government transfers are virtually unchanged (in real terms) since 1976; they earn little money from investments, and employment incomes have fallen.

The proportion of men who earn employment income each year has fallen since 1976, for every age group, except seniors, where it has risen considerably.

After inflation, average employment income for men under 35 was lower in 2023 than in 1976. For men between the ages of 35-44 and over 65, their employment income, when they have it, has just kept pace with inflation. For men between the ages of 45 and 64, real wages have increased by 17-18% over the last 47 years, an annualized increase of 0.35% per year.

In short, while economic outcomes for men over the age of 45 have improved in Canada since the mid-1970s, particularly for seniors, they have gotten worse for younger men. And this analysis does not account for the zero-sum nature of home price increases, which have financially benefited older, home-owning men at the expense of younger men who have yet to buy a home.