Designing Communities for the Middle Class: A Six-Question Test

A tool to challenge governments to deliver on middle-class homeownership.

Highlights

Too often in the middle-class housing space, policymakers and policy experts can become so engrossed in discussing the nuances of policy that they often lose sight of the broader picture.

To facilitate big-picture thinking, we have begun asking policymakers a sequence of six questions about middle-class housing at the community level.

These questions are designed to prompt policymakers to think through the community they are trying to create for the middle class and how far they are from achieving that goal.

Visualizing the forest, not just the trees

Here at MMI, we engage with numerous policymakers and officials, ranging from elected officials to municipal planners. Often, these conversations are about the merits of particular policies, and whether governments should choose policy X or policy Y, or about the intended or unintended consequences of policy Z.

While these conversations are quite fruitful, we often find it valuable to step back and start from first principles, allowing them (and us) to think through the problem we’re trying to solve. Policy wonks (ourselves included) can often become so engrossed in the nuances of specific ideas that we lose sight of the broader picture.

To facilitate big-picture thinking, we have begun walking policymakers through a series of six questions related to middle-class housing. These questions are at the community level, and we use the community in which the policymaker resides, regardless of the level of government they work for.

Here are our six middle-class related housing questions for policymakers.

Q1. Should your community be a place where a middle-class couple with two kids (a 9-year-old boy and a 5-year-old girl) can realistically expect to buy a home?

Note that the question does not ask if their community is currently such a place, but rather if it should be.

We suspect that the answer to this question would be a resounding “yes” from most (but not all) politicians and officials. If they answer “no” to this question, that the middle class should only be able to rent, not buy, then a different series of questions is needed.

Q2. In practical terms, what kind of home would fit the needs of this family of four? Include unit type, size, and number of bedrooms.

To meet the federal government’s implementation of the right to adequate housing under international law, this home must have at least three bedrooms. Otherwise, there is a lot of flexibility here, and we would expect a number of answers along the lines of “a townhouse of at least 900 square feet”.

Q3. According to traditional financial advice, a home shouldn’t cost more than three times the annual pre-tax family income. Do you agree, and, if not, what do you think is reasonable?

Answers to this will vary. Some will suggest three should be the standard, a handful might suggest something lower, such as two or 2.5, whereas others will say that the advice is dated and suggest a number in the 4-6 range. The answer will reveal a great deal about how they perceive middle-class affordability.

Q4. What’s the minimum pre-tax household income a young family with two kids would need to be considered part of the middle class in your community?

There is no right or wrong answer to this question, but it does reveal how the respondents view who is, and who is not, in the middle class. We suspect the most common answers will be around $100,000. In the income-based definition we use at MMI, it would be closer to $53,000.

By combining the responses to questions 2, 3, and 4, we have a conception of what the respondent believes is appropriate housing for this family, along with a maximum price. For example, if their responses were:

A three-bedroom townhouse of at least 900 square feet.

Maximum of three times pre-tax family income.

$100,000 in annual income.

Combining these three responses, we conclude that the community should have three-bedroom townhouses of at least 900 square feet, costing no more than $300,000.

Q5. Is it realistic for a family to purchase a 3-bedroom, 900+ square foot townhome for under $300,000 in your community? If not, what’s the lowest attainable price for such a home?

Where the portion in italics is replaced with the combined responses to questions 2, 3, and 4 will be.

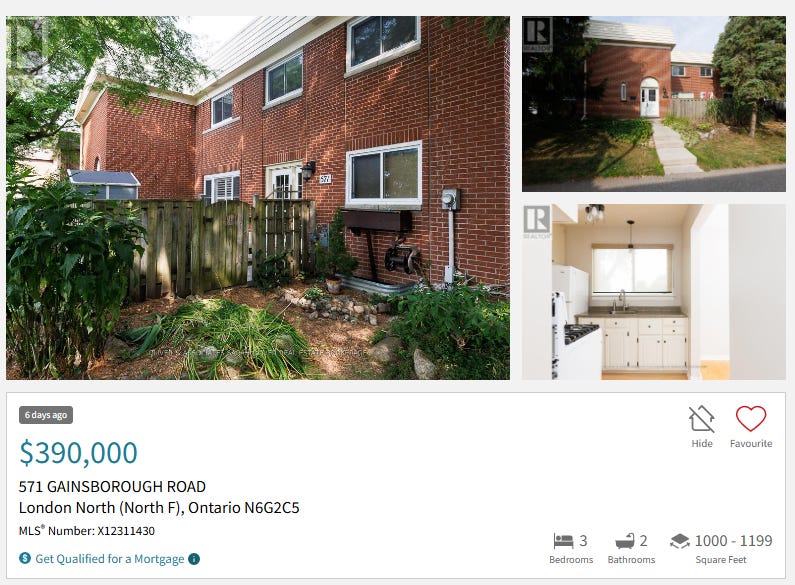

The answer to this question will be highly dependent on the answers to the previous three questions, as well as the chosen community. For example, in London, Ontario, it would be incredibly challenging to find a unit under $300,000, but one under $400,000 is achievable.

Figure 1: Real estate listing for London, ON

Source: Realtor.ca

So, while London doesn’t currently meet this criterion, it is reasonably close, with the caveat that $100,000 is quite high for a middle-class income cut-off point (although it is also the answer we have encountered the most often in response to this question).

Q6. What concrete policy actions are needed to ensure homes like this can be built and sold at that price in your community?

A very straightforward question. If the middle class needs 3-bedroom, 900+ square-foot townhomes for under $300,000 (as in our hypothetical responses to the earlier questions), what policy actions, if any, would help us achieve this goal?

I find this question helpful because if the disconnect between what prices need to be and what they currently are is quite substantial, so too must be the policy response. Needing prices to be $20,000 lower is a whole lot different than needing a $200,000 (or more) cut.

Getting the right answers begins with asking the right questions

We hope these questions catch on with other housing analysts and advocates, who adapt them for their purposes, such as those working on housing shortages for lower-income families, rather than the middle class. The purpose of these questions is not to embarrass policymakers, but rather to prompt them to think about the goals they are trying to achieve and the problems they should be addressing.