Did Development Charges Cause Metro Ottawa to Grow by Over 1000km in Size?

Part 1: An exodus of young families and the region's growing geographic footprint

Highlights

The City of Ottawa is geographically massive, with an abundant supply of land.

Despite the City’s size, communities just outside of the City have evolved into commuter towns for the City.

In 2014, the housing development industry warned that if the city kept increasing development charges, housing development would be pushed out of these communities. These warnings went unheeded.

The proportion of ground-oriented housing built just outside of the City of Ottawa (rather than in it) grew from 9% to 17%, as these communities attracted many millennials who worked in Ottawa but lived outside of it.

In 2019, Statistics Canada proposed adding Arnprior, Beckwith, Carleton Place, McNab/Braeside, and Mississippi Mills to its definition of metro Ottawa, as these municipalities had become commuter towns. The change would be adopted after the 2021 census was released.

This out-migration has substantially increased metro Ottawa's geographic footprint and put strains on the City’s finances. The City must provide and maintain road infrastructure for commuters who pay their property taxes to Arnprior and Mississippi Mills rather than to Ottawa.

Ottawa is massive. And a few years back, it got even larger.

After the release of Census 2021, Statistics Canada expanded the boundaries of Ottawa-Gatineau CMA (metro Ottawa) by 1280 square kilometers, an area nearly double the size of the country of Singapore, a country of 6 million people. Over 1,000km² of this was added in Ontario.

Statistics Canada expanded metro Ottawa's geographic footprint to include communities like Beckwith, Carleton Place, and Mississippi Mills because of an increase in the number of workers who live in those places but commute to Ottawa for work each day. These communities saw an influx of young families who moved in search of a high quality of life and attainable family-sized housing.

In 2014, the development industry warned the City of Ottawa that if it continued to proceed with a planned development charge increase, families would settle in smaller communities outside the City limits and commute back into the City for work, straining the City’s finances. This is exactly what happened.

There is a lot to unpack here, so let’s take it one step at a time.

The City of Ottawa is quite large

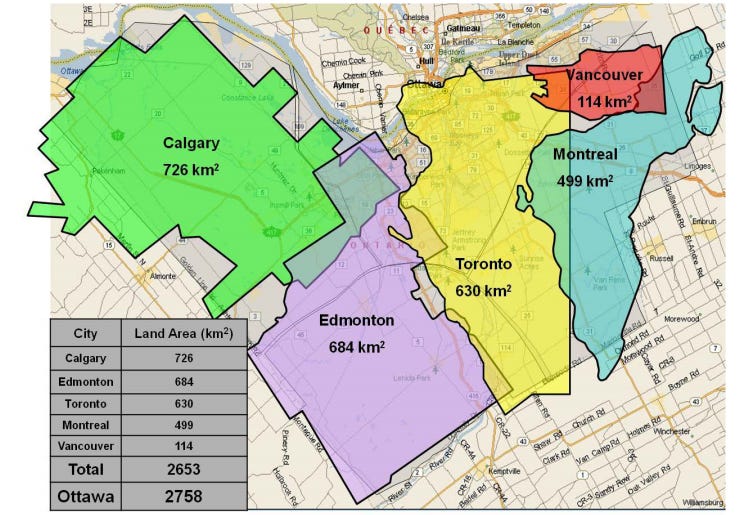

During the Mike Harris era, eleven municipal and regional governments were amalgamated into one, creating an absolutely massive single municipality: the City of Ottawa. The decision, which is still controversial today, created a mega-city of just under 2,800km². Guy Michaud best illustrated this in 2011 when he showed that the City was larger than Edmonton, Calgary, Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver combined.

Figure 1: City of Ottawa relative to other Canadian cities

Source: Ottawa Start

The City of Ottawa itself is already a big place. But Metro Ottawa is even bigger.

Metro Ottawa is massive

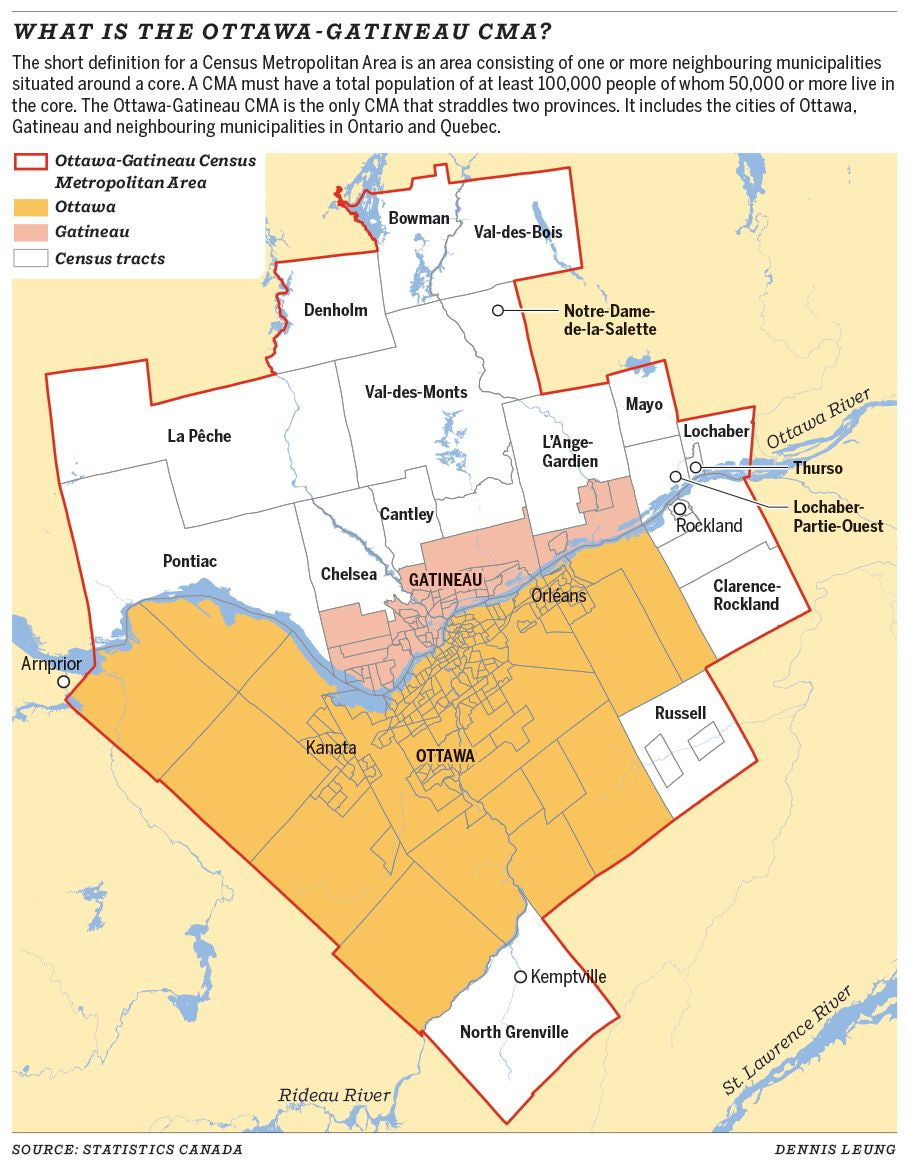

Metro Ottawa, or more accurately, the Ottawa-Gatineau Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), includes not just the City of Ottawa but also several communities in Ontario and Quebec. In 2016, the CMA included the City of Ottawa, many communities in Quebec, and three municipalities in Ontario: Clarence-Rockland, Russell, and North Grenville.

Figure 2: Ottawa-Gatineau CMA in 2016

Source: Ottawa Citizen.

While the City of Ottawa itself was 2,790km², the Ottawa-Gatineau metro was twice as large, due to the contributions of Gatineau and other communities in Quebec (3,128km²) and three additional municipalities in Ontario (849km²).

But what is a metro, anyway?

The technical definition for a metro is as follows:

A census metropolitan area (CMA) or a census agglomeration (CA) is formed by one or more adjacent municipalities centred on a population centre (known as the core). A CMA must have a total population of at least 100,000, based on data from the current Census of Population Program, of which 50,000 or more must live in the core... To be included in the CMA or CA, other adjacent municipalities must have a high degree of integration with the core, as measured by commuting flows derived from data on place of work from the previous Census Program.

The idea behind a metro area is that local economies are not contained by the (often) arbitrary borders of a municipal government. That people may live in Mississauga but work in Toronto, or live in St. Thomas and shop in London. The metro and its boundaries give a better indication of the true spread of a city than the municipal borders.

What determines the boundaries of the metro?

The methodology has changed over time, but it is largely based on work commuting flows. Under the current rules, there are seven ways a community (or more precisely a “census subdivision”, which in Ontario is usually a lower-tier or single-tier municipality) is added to a Census Metropolitan Area, with the most common ways involving that community having a large proportion of their labour force regularly commute to the CMA for work. In essence, they are added when they become commuter towns or bedroom suburbs of the metro.

Between 2001 and 2016, Statistics Canada added several communities to Ottawa-Gatineau CMA, always on the Gatineau side of the provincial border. That all changed in 2021.

What happened in 2021?

After the 2021 Census, five Ontario census divisions were added to the Ottawa-Gatineau CMA, along with Mulgrave-et-Derry in Quebec. Using the seventh of the seven ways of adding communities to a metro, the CMA absorbed the preexisting Carleton Place CA (census agglomeration), which contained three municipalities in Lanark County: Carleton Place, Mississippi Mills, and Beckwith. Statistics Canada also absorbed Arnpior CA into the CMA, which contained the municipalities of Arnprior and McNab/Braeside, both of which are in Renfew County. In short, the Ontario-side Metro Ottawa expanded westward by adding five municipalities from two CAs.

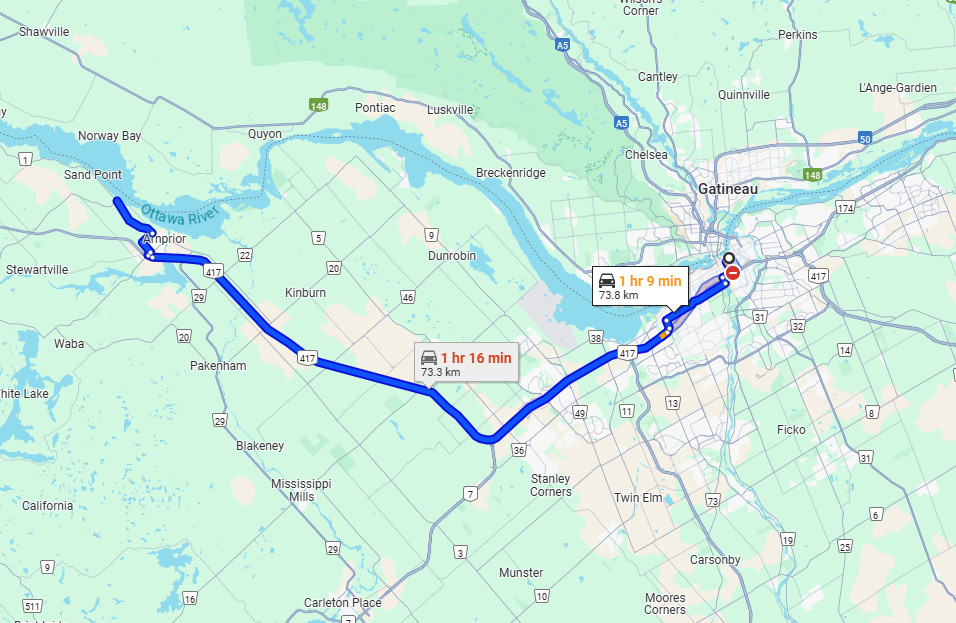

Figure 3: Directions from Ottawa to Braeside

Source: Google Maps

The decision to incorporate these communities into metro Ottawa was not surprising, and it was not due to the pandemic; Statistics Canada had publicly proposed the move in November 2019. It had become clearer that Arnprior CA and Carleton Place CA were exceeding the 35% commuting threshold to warrant inclusion as part of metro Ottawa.

In short, they became commuter towns; exactly what the development industry warned about in 2014.

Housing development post-2014

The development industry’s concerns were dismissed by the City in 2014, with the planning committee chair stating that smaller communities were growing as forecast and that “We haven’t seen [those communities] come forward and say, ‘We have to amend our official plan to accommodate more growth.’ ”

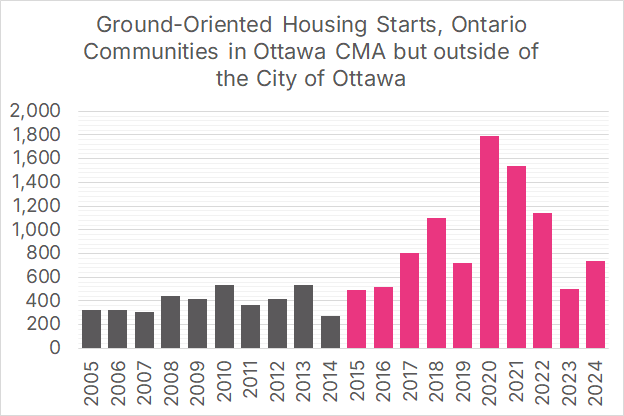

But faster growth is exactly what happened. Using data from the CMHC’s Housing Market Information Portal, we examined the number of ground-oriented housing starts that occurred in Ontario within the Ottawa CMA but outside the City of Ottawa. Those are the smaller communities on the Ontario side of the Ottawa-Gatineau CMA just outside the City of Ottawa, including the ones that were added to the CMA in 2021, as referenced in the earlier quote.

From 2005 to 2014, these communities averaged 395 ground-oriented housing starts per year. From 2015 to 2024, this would more than double to 934 starts per year, exactly as the industry had predicted.

Figure 4: Ground-Oriented housing starts, Ontario communities in Ottawa CMA but outside of the City of Ottawa, Number of Units

Source: CMHC Housing Market Information Portal

Ontario also experienced enhanced population growth after 2014, which caused housing starts to rise across the province, including in the City of Ottawa. As such, looking simply at raw unit counts could be misleading. We can control for this by comparing ground-oriented housing starts in these communities to those in the City of Ottawa. If we ask, “Did the proportion of ground-oriented housing starts occurring in the Ontario side of the Ottawa CMA but outside of the City of Ottawa increase?” The answer is a resounding “Yes!”

Figure 5: Communities in Ottawa CMA (Ontario-Side Only) but outside of the City of Ottawa’s Proportion of Ground Oriented Housing Starts

Source: CMHC Housing Market Information Portal

From 2005 to 2014, these communities accounted for 9% of the ground-oriented housing starts in the Ontario side of Ottawa CMA. In the following decade, they accounted for 17%. This doubling of market share is certainly aligned with the industry’s warnings. It is also not unique to Ottawa, as we showed in the report The Growth of London Outside of London.

However, this increase in homebuilding doesn’t show that new housing was added because people moved there (which the industry warned about). It is possible that these homes were only for people who already lived there, like those moving out of their parents’ home. Fortunately, we also have data on migration patterns, which can address this question.

Migration patterns post-2014

This was the subject of our earlier piece, Communities are Unprepared for the Exodus of Urban Families, but we can conduct a similar exercise examining just these Ontario Ottawa CMA communities that are just outside of the City of Ottawa. Outside two outlier years (2011-12 and 2016-17), we see a very clear rise in the number of people who move to these communities from elsewhere in Ontario (including from the City of Ottawa). Note that the data includes both inflows and outflows within the province and that this upward trend predates the pandemic by several years.

Figure 6: Intraprovincial migration, number of persons, Ontario communities in Ottawa CMA but outside of the City of Ottawa

Source: Statistics Canada Tables 17-10-0149-01 and 17-10-0153-01

Excluding the outlier 2011-12 year, there was very little net within-province movement in these communities. For every person that moved in from somewhere else in the province, someone moved out, keeping net interprovincial growth near zero. Note that this only considers population changes from migration within the province, and doesn’t incorporate other components of population change, such as births, deaths, and immigration.

In recent years, 3,000-4,000 more people from Ontario have moved into these smaller Ontario communities outside of Ottawa than have moved in the other direction. And they’re exactly who industry predicted they would be.

Millennials are the biggest cohort moving to these communities

When the City of Ottawa proposed a substantial increase to development charges in 2014, the industry indicated that the impact this would have on housing affordability would hit millennials particularly hard:

“We’re trying to focus on affordability (of housing) because it’s gradually disappearing,” he says. “The millennials starting families have historically been our biggest new home buyers, but they’re falling away.”

Statistics Canada data on migration includes a breakdown by age, so we can determine the ages of the people moving to these Ontario communities just outside the City of Ottawa. We can use the most recent data, which is for the year between July 1, 2023 and June 30, 2024. By dividing the population into 15-year cohorts that roughly coincide with generational definitions, we see that the majority of the net interprovincial movers into these communities are millennials.

Figure 7: Intraprovincial migration by age, number of persons, Ontario communities in Ottawa CMA but outside of the City of Ottawa, from July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024

Source: Statistics Canada Tables 17-10-0149-01 and 17-10-0153-01

In short, the people most likely to move to these communities are the young middle-class families who have been priced out of the City of Ottawa. They are the millennials who fell away.

Summarizing a decade’s worth of expansion

We can summarize the last decade’s events as follows:

In 2014, the City of Ottawa proposed a large hike to development charges.

In response, the development industry suggested that development charge hikes would cause homes to be built outside of Ottawa rather than inside it. The City dismissed this concern.

After 2014, the proportion of ground-oriented housing built just outside the City of Ottawa rose from 9% to 17%, despite the City’s massive geographic footprint containing abundant land.

The development industry suggested that Ottawa’s development charge increases would disproportionately impact millennials. Last year, millennials were disproportionately the group who moved to the communities just outside of Ottawa.

So many families who work in Ottawa moved just outside the City that, in 2021, Statistics Canada added the communities of Arnprior, Beckwith, Carleton Place, McNab/Braeside, and Mississippi Mills to the Ottawa-Gatineau CMA, as they had evolved into commuter towns. This change in designation was not due to the pandemic, as Statistics Canada had proposed the move in 2019.

This outward migration caused the City of Ottawa to lose tax revenue from these families while still having to build and maintain the road infrastructure needed to support these commuters, exactly what the development industry had warned about in 2014.

Everything the development industry predicted in 2014 came to fruition. Of course, a prediction can be correct for the wrong reason; perhaps factors other than development charges contributed to this. In a forthcoming piece, we will examine the last decade of development charge increases in the Ottawa region and their potential role in this out-migration.

Download a PDF of this article here: