Explained: Why an HST Cut Pushes Home Prices Down and Helps Build More Homes

A friendly explainer on a policy that would actually lower home prices, an outcome some governments desperately hope to avoid.

Highlights

Cutting the HST on new homes is a supply-side measure, not a demand boost: it lowers the cost of producing new units, increasing competition with resale homes, which are already exempt from the HST, and expanding the supply.

A mandatory 13% HST on new homes creates a significant cost disadvantage: On a $725,000 home, the tax adds over $70,000, even after rebates, making new builds uncompetitive against resale homes built under the far more favourable tax and regulatory environments of 20 and 30 years ago.

This artificial price premium forces builders into extreme strategies: With no middle ground, developers are pushed toward either tiny “less-for-less” shrinkflation products or oversized “more-for-more” McMansions.

Removing the HST would allow new homes to compete directly with the resale market: a $725,000 townhome could actually sell for $725,000, thereby increasing supply and putting real downward pressure on resale prices.

Governments hesitate to cut the HST because it would work: An HST cut would make homes more affordable by lowering resale prices, an outcome many governments are reluctant to be associated with, even if it helps families.

Listening to the competition

On a recent episode of the must-listen podcast The Herle Burly, Tyler Meredith offered his skepticism of the efficacy of reducing the GST or HST on new homes, stating:

Okay. David, if you remember, we had a housing pod on the Herle Burly a few months ago with with a few other folks, and Mike Moffatt made a strong pitch for uh taking GST off, which they’re currently doing for first-time home buyers, for new builds, but to extend that to everyone else because it would be a way to juice demand. And actually, if you juice demand, not only is that good for homeowners, it potentially will also create the conditions for people to want to build more, right? And the problem here, even I mean, you heard me say I think that’s a dumb idea, for I don’t understand, by the way, why that doesn’t just raise the price of houses.

Naturally, we disagree with Tyler’s description of the purpose of the measure. In “Boosting Demand for New Homes Is Supply-Side Policy”, we outline how new homes are fundamentally different than resale ones, so any policy that lowers the cost of building new homes (but leaves existing ones untouched) is boosting supply, not juicing demand.

Unfortunately, Tyler gets the economics of this 100% wrong. Eliminating the GST or HST on new homes lowers the price of resale homes. Here’s how.

The 13% price premium on new homes

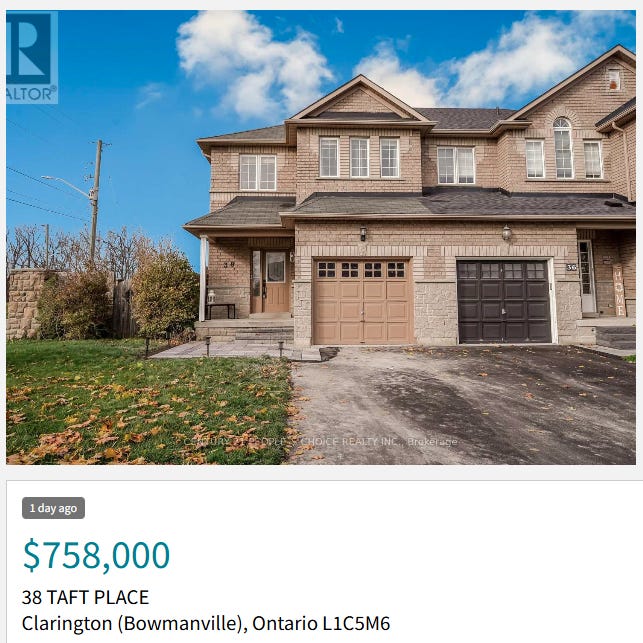

Suppose you’re a builder-developer operating in a community in Ontario where resale homes, similar to this freehold townhome, are selling in the $760,000 range:

Figure 1: A resale home in Bowmanville, Ontario

Data Source: Realtor.ca

You might think to yourself, “I could build something of similar quality, sell it for $725,000, undercut those resale homes a bit, and still make the math work enough to be able to make a profit”.

If you were able to produce these homes and sell them at that price, all else being equal, it would simultaneously increase the supply of new homes and drive down the cost of resale homes. Resellers, having to compete with new build, would not be able to compete without cutting their prices by tens of thousands of dollars.

Except you can’t do this as the new home builder, because, unlike the reseller, you must charge a 13% HST on your newly constructed Ontario home. This would add $94,250 to the final price of the home, though the province does offer a $24,000 tax rebate (whereas this home would be ineligible for federal rebates, unless a first-time homebuyer purchased it), which adds $70,250 to the price of the home.

That $725,000 home has now become a $795,000 home, and is no longer cost-competitive with a $758,000 resale. The builder is then left with three options: cut the price of the home, increase the quality of the home, or don’t build at all.

The first option is competing on price, which involves the builder cutting costs as much as possible to make the math work, thereby getting prices low enough to attract buyers. Yard sizes are reduced, full bathrooms are converted to half bathrooms, and condo units are downsized to the size of shoeboxes. The classic “less for less” strategy, which has led to housing shrinkflation.

Another option is to adopt a “more for more” strategy and justify higher price points by larger, more feature-rich homes. More bedrooms, more bathrooms, a massive theatre room in the basement, you name it. In other words, McMansions.

One of the most common refrains we hear at MMI is, “The only thing that developers build these days are shoebox condos, and McMansions, there are no reasonable-sized new homes anymore.” While that is overstated, this bifurcation of the market is real. Industry players have had to adopt “less for less” and “more for more” strategies, as new builds have an incredibly tough time competing against resale supply that was constructed under much more favourable tax and regulatory conditions of decades past.

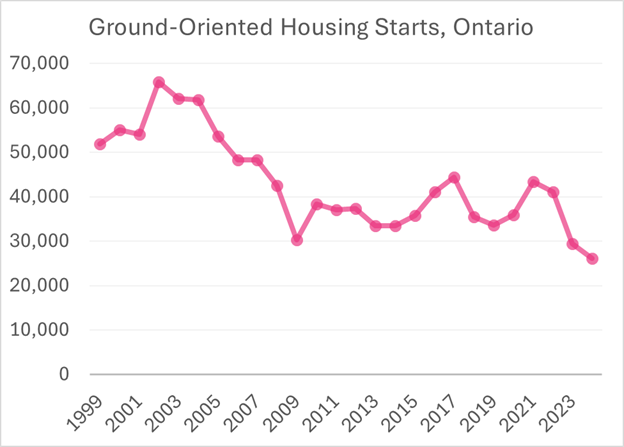

There is simply no way to cost-competitively build the new London, Ontario home that Mike bought in 2004, given that construction taxes on the home have increased by over 500% and land use restrictions are far more stringent. Developers have either gone up-market, down-market, or are not building at all, with ground-oriented housing starts down over 60% since the 2002 peak, despite a massive increase in the rate of population growth.

Figure 2: Ground-oriented housing starts, number of units, Ontario

Data Source: CMHC Data Portal, Chart Source: MMI.

If governments were to eliminate the HST on new homes, however, new housing would have an easier time competing with resale, as there would be no artificial 13% price premium (excluding rebates) on new construction in Ontario. Our builder-developer may now be able to offer the $725,000 townhome, creating increased supply and forcing resellers to lower the price of their units if they want to compete. New homes would be built, and young families would have more options and lower prices.

An HST cut is not a silver bullet; new homes still face significantly higher development charges, substantially longer approval times, and higher land costs due to far more stringent land-use restrictions than homes built 20 or 30 years ago. However, it would go a long way toward making new construction more cost-competitive, which would increase the housing supply and lower the price of homes. This may explain the reluctance of some governments to adopt an HST cut for housing; after all, if your goal is to ensure a “stable” market, then you are unlikely to support a measure that leads to falling resale prices and enhanced affordability.