From Vancouver to Montréal, Canada's Housing Engine Is Stalling

The belief that Canada's housing construction slowdown is simply a Toronto condo problem is a misreading of the data

Highlights

The problem is larger than it appears: Many policymakers believe Canada’s slowdown in new housing activity is confined to condos in Toronto (and possibly Vancouver). While it may have started there, the reality is that new housing activity is collapsing across all types of housing ownership in Canada’s major markets, including Calgary, Edmonton, and Montréal.

Housing starts are a lagging indicator that can mislead: Recent housing starts data, in isolation, suggest the slowdown in new housing is confined to the GTA and primarily to the condo market. While housing starts are down 37% year-over-year in Toronto (and Toronto condo housing starts are down 57% year-over-year), starts are up in most of the rest of the country. However, housing starts reflect decisions made several years prior; they are a poor indicator of current market conditions.

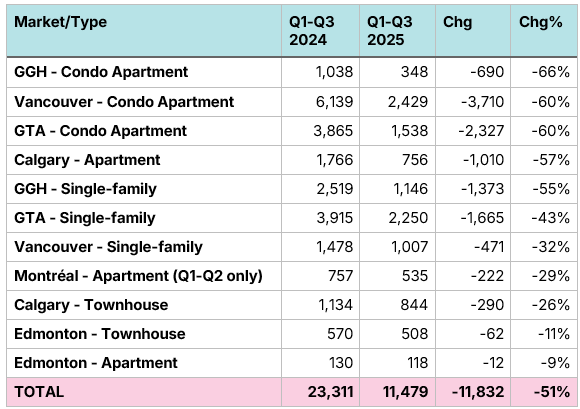

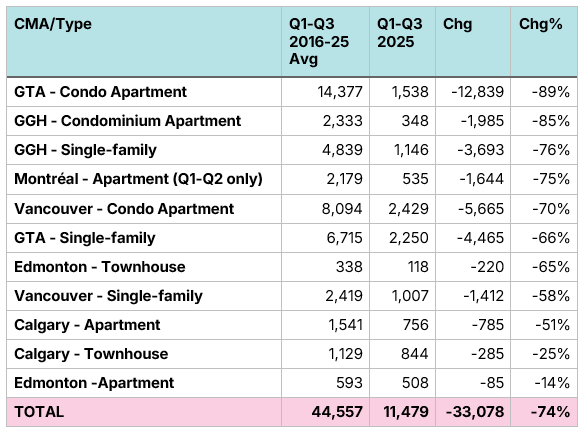

New housing sales provide a real-time view of the decline in large markets across the country: Using data from Altus Group, obtained by BILD, we find that across six of Canada’s largest housing markets (GTA, Greater Golden Horseshoe, Vancouver, Montréal, Calgary, Edmonton), new home sales are down 51% relative to last year. This includes a 57% decline in Calgary condo sales and a 55% decline in single-family home sales in the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

When housing sales decline, employment is sure to follow: Using the standard multiplier of 1.5 person-years of employment for apartment units, and 3.8 person-years of employment for ground-oriented homes, we estimate the reduction in housing sales over the first nine months of the year in these six markets will lead to 26,000 fewer person-years of employment relative to last year, and 72,000 fewer relative to 2016-25 averages.

When housing dysfunction goes viral

New data from Altus Group, obtained by BILD, reveals that Canada’s new housing slowdown is more widespread than previously thought. In six of Canada’s largest housing markets (Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Montréal, and the non-Toronto portion of the Greater Golden Horseshoe), new home sales in the first three quarters of 2025 are down 51% relative to the same period in 2024, and down 74% from 2016-25 Q1-Q3 averages. Relative to last year, condo sales are down 66% in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, 57% in Calgary, and 29% in Montréal.

The declines are not isolated to the condo market either, as new and pre-construction single-family home sales are down 55% in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, 43% in the Greater Toronto Area, 32% in Vancouver relative to last year, with townhome sales dropping 26% in Calgary and 11% in Edmonton.

A reduction in new home sales eventually leads to fewer new housing starts and completions, moving us further away from the federal government’s goal of doubling housing starts. This housing activity decline impacts the labour market as well; applying Statistics Canada multipliers to these sales drops finds that it will reduce housing-related employment by 26,000 person-years relative to 2024 housing sales levels, and by 72,000 relative to 2016-25 levels.

Despite this collapse in new housing sales, the federal government has shown continued reluctance to act. This reluctance may be due to the government drawing the wrong conclusion, because they are looking at the raw data.

Examining the wrong numbers

The media is full of stories on the complete collapse of Toronto’s pre-construction condo sales market, and how fewer sales today will mean fewer housing starts and completions in years to come; in fact, we have written a few of these ourselves. These pieces, which MMI has contributed to, have led many, including policymakers, to believe the slowdown is confined to the condo market and to Toronto, and, to a lesser extent, Vancouver.

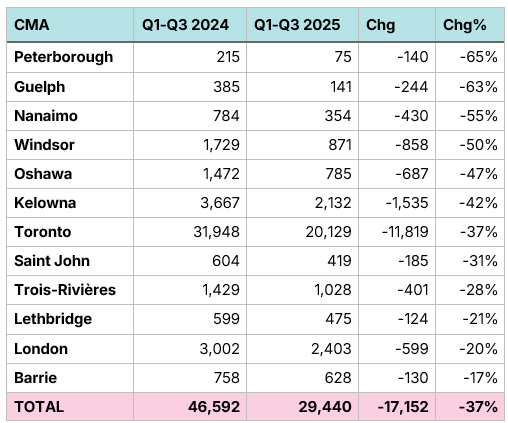

Adherents of the “it’s only a Toronto condo problem” argument have those beliefs backed up when examining housing starts data. Figure 1 lists all of the metro areas where housing starts are down more than 5% year-over-year. The only large housing market on the list is the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), with the rest of the list composed of markets closely tied to the GTA (Peterborough, Guelph, Oshawa, and Barrie).

Figure 1. Housing starts, Q1-Q3 2024 vs. Q1-Q3 2025, CMAs with a decline of over 5%

Data Source: CMHC Housing Market Portal, Chart Source: MMI

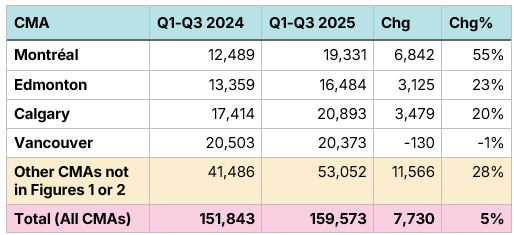

Three of Canada’s next four largest markets show robust housing start growth, with the fourth, Vancouver, experiencing relatively flat growth. Overall, housing starts are up 5% year over year nationwide.

Figure 2. Housing starts, Q1-Q3 2024 vs. Q1-Q3 2025, other large CMAs

Data Source: CMHC Housing Market Portal, Chart Source: MMI

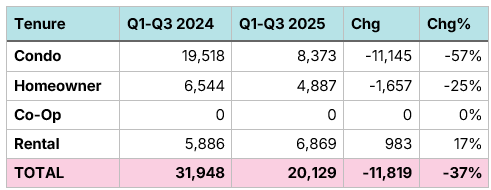

Diving deeper into the GTA reveals that most of the net decline in starts comes from new condo starts, which are down 57% year-over-year, a decline of over 11,000 units. A reduction in freehold ownership (1,657 units, a 25% reduction) has been somewhat offset by a rise in purpose-built rental starts (983 units, a 17% increase), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Housing starts, Q1-Q3 2024 vs. Q1-Q3 2025, Toronto CMA by intended tenure

Data Source: CMHC Housing Market Portal, Chart Source: MMI

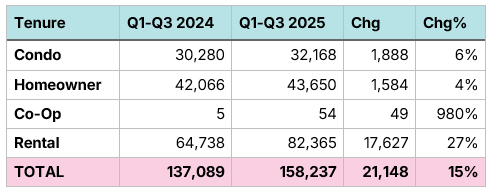

Across the rest of the country, condo and freehold ownership starts are largely unchanged from last year, while purpose-built rental starts are up 27%.

Figure 4. Housing starts, Q1-Q3 2024 vs. Q1-Q3 2025, CMAs except Toronto by intended tenure

Data Source: CMHC Housing Market Portal, Chart Source: MMI

All of this data suggests that Canada’s new housing dysfunction is confined to Toronto condos. However, housing starts are a lagging indicator, a point that we have repeatedly made at MMI. Because the CMHC only counts a project as a start until the foundation is complete and at grade, it reflects the state of the housing market 18-36 months prior, when the decision to proceed with those projects began.

New housing sales, not starts, tell the real-time story

For a more real-time indication of the market’s health, housing analysts, policymakers, and the media should be looking at new home sales, not housing starts. There are limitations to using sales data; it is difficult to obtain, as the CMHC does not publish it, unlike housing starts. Furthermore, by definition, it excludes purpose-built rentals. Despite those limitations, it remains the best leading indicator we have of the market’s health.

Earlier today, BILD published new housing sales data, obtained from Altus Group, for six of Canada’s largest markets for the first nine months of the year, along with the equivalent data for 2024 and a 10-year average for the first nine months of the year. For the 11 location/housing-type pairs in the release, nine have experienced reductions of 25% or greater relative to 2024. These declines are not isolated to Toronto, as new condo sales are down 66% in the non-GTA portion of the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH), 60% in Vancouver, 57% in Calgary, and 29% in Montréal. Nor are they isolated to apartment condos, as single-family home sales in GGH, GTA, and Vancouver are down over 30% relative to last year, and Calgary townhome sales are down 26%, as shown in Figure 5.

Overall, new home sales are down by nearly 12,000 units, or more than 50%, in the first nine months of 2025 relative to the first nine months of 2024. Using Statistics Canada multipliers of 1.5 person-years of employment per apartment unit completion and 3.8 person-years of employment per non-apartment unit, we estimate a reduction of 26,628 person-years of employment across these six markets from the decline in new home sales.

Figure 5. Pre-construction and new housing sales, Q1-Q3 2024 vs. Q1-Q3 2025, five large Canadian markets, by type

Data Source: Altus Group and BILD, Chart Source: MMI

While a 51% year-over-year drop in new housing sales is dramatic, it arguably understates the level of decline, as 2024 was a particularly weak year for new housing sales. In Figure 6, housing sales for the first nine months of 2025 are compared with 10-year averages for the first nine months of the year. They reveal a 74% drop in new and pre-construction sales across our six markets, with 9 of 11 location/housing-type pairs experiencing drops of 50% or more. Every one of our six markets has experienced a drop of over 50% in sales for at least one housing type. Plugging these sales figures into Statistics Canada’s multipliers yields an estimated reduction of 72,746 person-years of employment.

Figure 6. Pre-construction and new housing sales, Q1-Q3 2016-25 Avg vs. Q1-Q3 2025, five large Canadian markets, by type

Data Source: Altus Group and BILD, Chart Source: MMI

Solving the paradox of needing lower home prices and increased housing construction

The causal explanation for this sale in new home activity is relatively straightforward: prices have fallen due to reduced demand, and this price reduction is necessary to help restore affordability across Canada. However, the cost of building homes has remained stubbornly high and, in many cases, continues to rise. These twin forces have created conditions where it is no longer economically viable to build, and families in the housing market are better off buying a resale home than a new one.

This price-cost dynamic was a point that MMI’s Mike Moffatt recently made to the Canadian Senate:

Across much of Canada, home prices and rents have fallen in recent years. For families that have spent years on the outside looking in, that should be welcome news. Yet affordability remains elusive. Home prices are still far beyond the reach of most middle-class households, while the cost of construction remains stubbornly high. In many markets, the total cost of building now exceeds what families can afford. This creates a paradoxical situation where homes are both unaffordable for buyers and uneconomic to build. The only sustainable path toward attainable prices and increased housing supply is to lower construction costs, which means cutting the taxes that drive those costs up...

Governments claim to want more housing, yet their tax systems make it increasingly uneconomic to build. The combined burden of the GST, PST, development charges, and fees can add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of a new home. When I bought a new home in London, Ontario, in 2004 for $168,000, the taxes and fees were under $16,000. Today, the taxes alone on a similar home are roughly that much. These costs directly determine whether a project can proceed, and as prices fall while taxes stay high, more builders are shelving projects.

Some argue that cutting housing taxes would result in governments losing too much revenue. In reality, the opposite is true. Our estimates show that the federal government will lose over $3 billion annually in forgone revenues from the GTA and Vancouver alone if construction continues to decline, exceeding the entire budget of the Build Canada Homes program. Taxing new homes out of existence is not a fiscally prudent approach.

Housing cannot be both a right and taxed like a luxury yacht. Ottawa imposes a 10 percent luxury tax on yachts worth over $1 million, yet a middle-class family buying a semi-detached home in Scarborough pays the equivalent of 15 percent in development charges and land transfer taxes, plus GST and PST on top of that. If we want to make quality homes affordable again, we must stop taxing them out of existence.

While Canada’s new housing dysfunction may have started with Toronto condos, it has spread to other markets and other housing types. If policymakers wait for these drops to be reflected in the housing starts data, it will be too late. The time to act is now.

Download a PDF of this article below