Municipal Timelines: Miracle or Mirage

Are the claimed improvements in application timelines real or an illusion?

Highlights

Some Ontario municipalities have reported an 80% to 90 % improvement in application review times, but this claim is a measurement illusion. It results from implementing workarounds in response to provincial policy requiring application refunds rather than from substantive changes.

The workarounds include creating a pre-application consultation process (PAC) that allows for review work to be done without days being counted, increasing report requirements to lengthen the PAC process, and increasing the use of rejections.

None of the workarounds provides applicants with lower risks or costs that would increase housing supply.

The workarounds that municipalities are using make it impossible to track the effects of tangible improvements.

The efficiency claims do more to degrade, rather than inspire, confidence in the development review process and the planning profession charged with managing it by failing to provide the public with a consistent measuring stick to measure municipal timelines.

With the province reversing course on its refund policy, municipalities no longer need to use their alternative timeline accounting methodology.

The City of Toronto makes a bold claim

In their review of development application fees1, Toronto claimed that:

“… [application] review times have improved by over 80 percent when compared to the previous 5-year average.”

This would be a miracle if true, but much of the timeline improvement being claimed by Toronto and other municipalities in Ontario comes from a mirage created by changing the way application timelines are counted through three primary workarounds rather than from actual improvements. These workarounds were a response to Ontario’s Bill 109 and have made it impossible to properly assess the impact that process improvements are having on application timelines. This has also caused a deterioration in the application process.

Bill 109 changes the landscape

Prior to the passage of Bill 109, if a municipality failed to meet the decision timeline set by the Planning Act, an applicant could appeal to the Ontario Land Tribunal2 (OLT) for a ‘non-decision’ and seek an approval through the OLT.

Bill 109 introduced a policy requiring a municipality to progressively refund fees it received to review an application if it failed to render a decision within 60 to 120 days, depending on the application type.

The refund policy went into effect on July 1st, 2023, and almost immediately, municipalities started to claim improvements in application timelines by 80% to 90%. When you see a municipality refer to ‘July 1st, 2023’, or ‘Bill 109 Applications’, they are referring to submissions affected by this policy.

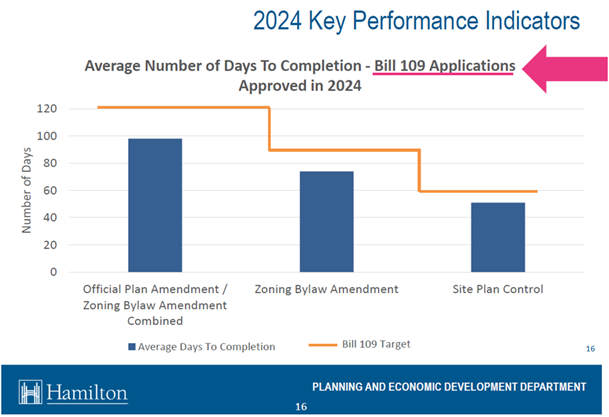

For example, Hamilton staff presented their Bill 109 applications to suggest that an applicant can expect to receive a decision within 55 to 100 days, depending on the application type. The implication is that this is a representative experience of the development review process in the city. Unfortunately, it’s anything but.

Figure 1: 2024 Application Key Performance Indicator for City of Hamilton

Source: City of Hamilton

Municipalities had a number of options, all unpleasant

Development application fees fund the salaries for large sections of planning departments. Threatening this source of revenue was a major problem for municipalities, as Altus Group3[1] noted in their 2022 GTA Municipal Benchmarking Report:

“Given that both municipalities and many applicants agree that the difficulty attracting and retaining planning staff is a major issue that contributes to long approval timelines, removing three-quarters of planning application fees, which go towards funding staff salaries, is unlikely to have any positive effects on the ability of municipal planning departments to be adequately resourced to improve application timelines.”

With this context, municipalities saw four potential responses to the refund policy:

Major staffing cuts.

Pay a larger portion of planning staff salaries from revenue sources like property taxes.

Approve applications without what they felt were sufficient review times.

Use alternative workarounds that make it appear timelines were being met.

From a municipality’s perspective, the first three options were highly undesirable, so they defaulted to the fourth one, an unintended consequence many analysts had predicted would occur.

In theory, the refund policy should have incentivized municipalities to make decisions more quickly, but in practice, the harshness of the penalties left municipalities with little option but to choose the workarounds.

The workarounds

To varying degrees, municipalities adopted three primary workarounds to meet the refund policy timelines by:

Moving much of the review process into a ‘pre-application consultation’ (PAC) phase, which isn’t counted in official timelines.

Increasing application requirements to delay when the clock began.

Increasing the rate of application rejections when timelines couldn’t be met.

Not all municipalities adopted every one of these workarounds or used them to the same degree. Each municipality was situational in its approach, with factors such as the complexity of proposals (e.g., proportion of low-rise vs. high-rise projects), volume of applications, litigiousness of local homebuilders, etc. influencing how and when they adopted these workarounds.

These actions don’t discount that municipalities have made some good faith attempts at improvements; however, it’s not possible to identify their impact in any analysis that includes Bill 109 applications because applications containing those workarounds are present.

Workaround 1: Meeting the goal by moving the goal posts

In Ontario, there is a concept called a ‘complete application’, which is when a municipality legally acknowledges that an applicant has provided payment for all applicable fees and submitted all the necessary reports to begin reviewing an application. This is the point when a timeline begins being tracked under the law.

Municipalities recognized that they could create a required ‘pre-application consultation’ (PAC) phase where a lot of the review process could occur before an application would be acknowledged as complete. This was a widely recognized response to Bill 109, with Urban Strategies, a major planning consultancy firm in Ontario, noting:

“…the pre-submission consultation and review process plays a critical role in determining the trajectory of an application after the clock starts on the Planning Act timelines. However, it also represents a potentially lengthy and unstructured phase in the process that has the risk of taking on a life of its own…

Given these highly compressed [Bill 109] timelines, much of a municipality’s review and comment on a proposal will now happen in advance of the formal submission….

The lack of clear timelines associated with new mandatory pre-application processes has been a particular concern of the development community. Applicants are reluctant to expend significant time and resources honing a proposal in the pre-application period if the outcome is so uncertain, and if municipal staff are not able to meaningfully engage in the face of other active applications with timeline pressures.”

Essentially, what used to be covered during the formal application process would now be done through an uncounted PAC phase.

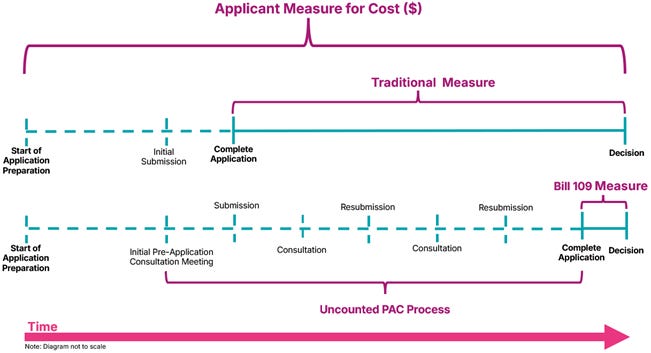

From an applicant’s perspective, the time cost of a planning application begins the day resources start to be spent preparing it and ends with a decision,4 hopefully an approval. The traditional timeline measure was able to, although imperfectly, account for much of the applicant experience.

While it didn’t consider the portion of time before a municipality received a submission, the traditional measure was accepted by both homebuilders and municipalities as it was a fair and balanced point between their interests.

The PAC process that Bill 109 induced caused municipalities to tilt the balance by putting time they previously counted officially and making it unofficial, despite doing work that would have previously been considered ‘review’, as Figure 2 illustrates. Also, the PAC process required applicants to pay for the time city planners spent on review work, something that previously would only be done to trigger a complete application acknowledgement in most cases.

Figure 2: Applicant, Traditional, and Bill 109 Timeline Measurements

Source: Missing Middle Initiative

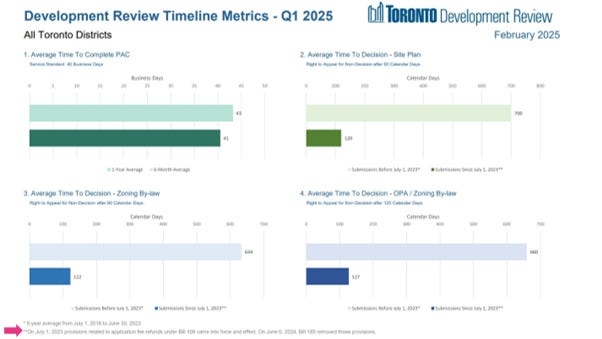

Toronto's claim that “review times improved by 80%” is taken from its Q1 2025 Development Review Time Metrics. The review compares applications submitted five years before July 1st, 2023, to applications submitted after this date (Bill 109 applications), as they note in fine print.

Figure 3: Toronto Development Timeline Metrics – Q1 2025

Source: City of Toronto

As Figure 2 illustrates, the calculation used to derive Toronto’s 80% improvement is not apples-to-apples, as it compares applications that had to undergo a required and uncounted PAC process to those that did not.

Workaround 2: Increasing application requirements

Another workaround that was employed to increase PAC timelines was to increase the number of reports required for an application to be considered complete.

In the PAC process, through meeting after meeting, reports would be progressively submitted as they were completed, reviewed by staff, and then the next set of reports/meetings would occur. Having more reports would trigger more meetings, which in turn would give staff more uncounted time to review applications.

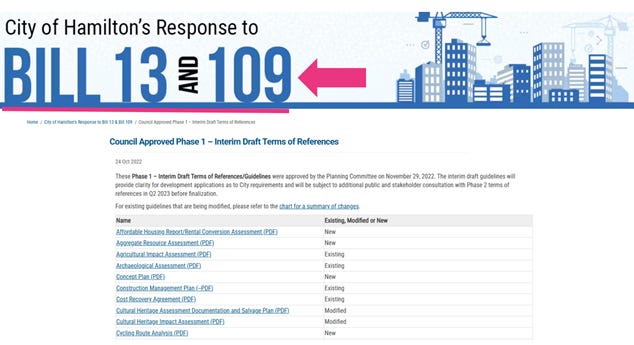

Municipalities were very transparent about increasing application requirements in response to Bill 109. For example, Hamilton sought to increase the number of required reports from 45 to 93.

Figure 4: Hamilton’s Study Requirement Response to Bill 13 and 109

Source: City of Hamilton

Raising application requirements had a two-fold negative impact. First, it made the lives of public planners reviewing applications more difficult as they had to now wade through more potential report requirements to determine what was and wasn’t appropriate to ask for. Second, it caused more instances of applicants being asked for reports that weren’t necessary.

This inefficient process increased the cost and time associated with the review process for both municipalities and applicants, ultimately delaying and deterring new housing construction.

Workaround 3 – Rejection as a final option

Approving homes faster is not the same as making a decision faster. While Bill 109's stated intent was to promote the former, its incentive structure was geared toward the latter.

While data on approvals and rejections are very difficult to come by, Toronto staff have been uniquely transparent about Bill 109 application decision-making. Although it’s varied over time, Toronto has rejected between 45% and 63% of Bill 109-era site plan applications to ensure compliance with timelines and avoid refunds.

It's not known how widely other municipalities used rejections as a timeline strategy, but in Toronto’s case, when it claims to have made decisions faster, this includes a substantial portion of rejections.

The goal of reforming planning was to lower applicants' costs and risks, but this has done the opposite. The longer the lead time for planning approvals, the greater the risk, and the higher the return/price required to make a housing project viable. Trading in a lower risk associated with a faster timeline (on paper) for a higher risk of rejection does not balance out, given the level of rejection Toronto displayed.

The province reverses course

In June 2024, in response to the issues caused by the workarounds, the province eliminated the refund policy, along with the ability for municipalities to have mandatory pre-consultations, through Bill 185. The province has also proposed freezing the ability of municipalities to add new types of report requirements to give itself time while it creates regulations through the recently announced Bill 17. There would be no reason for the province to take these actions if timelines had truly improved by 80%-90%.

The decision to claim an 80% process improvement is unusual, as it raises the obvious question: “How inefficient are existing processes if a relatively small reform could lead to a 5x speed improvement?” The efficiency claims do more to degrade, rather than inspire, confidence in the development review process and the planning profession charged with managing it.

These speed improvements were a mirage, rather than a miracle, caused by a series of workarounds. In some cases, municipalities got themselves into legal trouble for trying to use consultations as a delay mechanism. The public deserves full, clear, and accurate statements—a claim of an 80-90% speed improvement, based on an apples-to-oranges comparison, fails to meet that test.

The solution to this problem is improved public availability of data from the development review process. This includes timelines and additional statistics so that a data-driven, evidence-based discussion is possible.

Download a PDF version of this article below

These are fees charged to review planning applications, which fund many of the planners that a municipality employs.

Formerly the Land Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) and Ontario Municipal Board (OMB)

Alex Beheshti, who is a member of MMI, was then part of the Altus Group team that authored all editions of the Municipal Benchmarking Report

To keep Figure 2 manageable, it does not incorporate appeals that are possible from a rejection.