Not everyone's housing vision includes ownership as a viable option for the middle-class

It's not our view, but it's a view

When worldviews collide

One thing you learn very quickly on the internet is that not everyone shares your views. And that certainly applies to middle-class housing, although we occasionally make the mistake of believing our views are universally shared.

For example, the first question in our piece, Designing Communities for the Middle Class: A Six-Question Test, asked the question “Should your community be a place where a middle-class couple with two kids (a 9-year-old boy and a 5-year-old girl) can realistically expect to buy a home?” The piece assumed that, so long as the recipient understood that the question was not asking if the community is currently such a place, but rather if it should be, the answer would be “yes”.

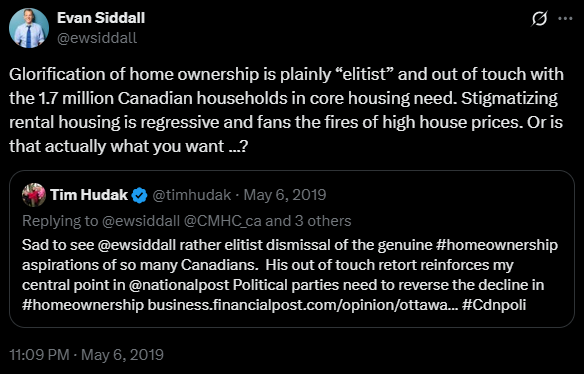

The “glorification of homeownership”

But not everyone would agree with this answer. In a 2019 speech, the head of the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Evan Siddall, talked about the need to “call out the glorification of homeownership for the regressive canard that it is”. He spoke of the need to rebalance Canadian housing policy, noting that "the [o]ver-promotion of homeownership is both economically and socially counter-productive, contributing to the increasing division between rich and poor.”

It was not the first time he warned against, in his view, the “glorification” of homeownership:

In his view, too much homeownership is harmful, stating “[h]omeownership is like blood pressure: you can have too much of it”.

Evan is not alone

The viewpoint that public policy needs to de-emphasize homeownership, accept (or encourage) a Canada where the middle class is priced out of owning housing, and transition to a society with a higher proportion of renters is relatively common. Some examples:

Ricardo Tranjan, author of “The Tenant Class”, a book that discusses the harms caused by a “society where home ownership is seen as the most important hallmark of a successful life,” notes that public policy has focused “quite a lot on home ownership as the ultimate in desirable outcomes for families”.

Armine Yalnizyan has warned about the problems of the “ownership society concept.”

In a primer prepared for the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate, Steve Pomeroy describes housing policy in Anglo-American countries as “favour[ing] individual rights and homeownership”. In the Toronto Star, he noted that Canada is part of a “North American frontier culture that creates policy bias toward ownership”, and that while homeownership may be good for individual middle-class families, it has had “consequences for society as a whole”.

Graham Haines, of the Ryerson City Building Institute, has been vocal about how governments have focused “exclusively on policies to promote home ownership over the last 20-plus years” and the need to think through the implications of a Canada where rental is “a more important part of our real estate sector.”

David Hulchanski has written extensively on the “systemic bias” of Canadian housing policy, which favours homebuyers over renters, a point echoed by Maytree.

University of Waterloo’s Martine August notes that “the promotion of homeownership” has “catalyzed the financialization of housing”.

Generation Squeeze has called for more purpose-built rentals and fewer condos.

John Lorinc has flatly stated that “Canada could do well to become a nation of renters”.

A number of mainstream media pieces have explored the idea of the end of middle-class homeownership, including Brad Badelt in The Walrus and Michelle Cyca in Maclean’s.

Often, the view on the need to shift to rental housing is one borne out of pragmatism, rather than an explicit rejection of middle-class homeownership. Examples include a Carolyn Whitzman report on deeply affordable housing, which bluntly states, “[h]omeownership is out of reach for all but higher-income households”, and a report by Dr. Ren Thomas, Dr. Markus Moos and Samiya Dottin that states “rental housing has emerged as a critical housing and tenure type in the housing continuum now that market ownership is out of reach for many”.

Finally, it is essential to note that these calls to reduce middle-class homeownership (whether due to policy concerns or pragmatic considerations) typically only indicate a direction of a shift, not its magnitude. How much middle-class homeownership should be reduced could only be determined through analyzing the policies advocated by these groups and individuals, or if they explicitly stated it.

A call for clarity

Unfortunately, it is exceptionally rare to see groups in Canada set out an explicit vision for middle-class housing. At the Missing Middle Initiative, we make it explicit that homeownership must remain an option for Canada’s middle class:

Missing Middle Initiative’s North Star: A Canada where every middle-class individual or family, in every city, has a high-quality of life and access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options that are affordable, adequate, suitable, resilient, and climate-friendly.

We define the middle class as individuals who are neither in the top 10% nor the bottom 20% of the population, typically determined by income (although we also acknowledge that alternative definitions are acceptable). We also make it clear that the middle class should have access to both rental and ownership options, and that one is not inherently superior to the other.

We believe it is helpful for housing advocates to provide a clear vision of success, enabling us to understand better the outcomes they aim to achieve when promoting policy. And, in particular, whether or not that vision of success includes housing ownership options for the middle class.