Ontario Development Charges: Everything You Wanted to Know But Were Afraid to Ask

A primer on the fastest growing expense in Ontario housing

Highlights

Collectively, municipal housing taxes in Ontario, including development charges, can make up 25% or more of the cost of a new home. Couple all these taxes with those from other levels of government, like land transfer taxes, the GST and HST, and, in some Ontario cities, these taxes can add up to over $250,000 on even a relatively modest family home.

Despite their contribution to Ontario’s housing affordability crisis, development charges are poorly understood. This primer seeks to fix that.

Previous pieces on Ontario development charges have covered everything from the scope of the problem to the issues at play to the state of things. But what we have yet to cover are the very basics. Let's fix that.

An alphabet soup of municipal housing taxes

The discourse around development charges in Ontario can be confusing, as the term "development charges" is often colloquially used to cover all forms of municipal housing taxation or "growth funding tools" in planner-speak. However, development charges (DCs) are only one of an alphabet soup of municipal housing taxes, which can include community benefit charges (CBCs), parkland dedication and other charges. To avoid confusion, we will use "development charges" to refer to the specific tool and use terms like "housing taxes" when referring to the entire alphabet soup.

To make it even more confusing, in some cases non-municipalities in Ontario can also levy development charges, such as school boards (educational development charges) and GO Transit.

It's all about choices

DCs are governed by the Development Charges Act (DCA), which is provincial legislation that outlines the legal framework for when, what, and how development charges can be used. Ontario municipalities are not legally required to use development charges, with 216 of 444 (48.6%) choosing to do so according to financial returns.

There is more than one development charge

The term ‘development charges’ is plural as municipalities must have separate charges for each infrastructure service they collect revenues for. For example, there are separate DCs for fire and police, as well as for roads and transit. All the revenue collected must be put into separate reserve accounts and only used for the purpose for which it was collected. There are many rules and many exceptions to those rules. For instance, revenue collected for roads can't be used to fund a library, although that road money can be loaned out to build a library.

Because each service has its own separate charge, in jurisdictions where there is a two-tier municipal government structure, each tier collects a separate set of charges based on its responsibilities. For example, Peel Region (upper-tier) charges a police development charge while Mississauga (lower-tier) charges for libraries, whereas Toronto (a single-tier municipality) charges for both.

As service responsibility can vary between upper-tier jurisdictions, the services that each charge for can likewise vary. For example, in one region, water infrastructure can be the responsibility of the upper-tier municipality and appear on development charge schedules for that jurisdiction, while in another region, it's the responsibility of the lower-tier and consequently appears on the lower-tier schedule.

Therefore, when comparing development charges between cities, it’s necessary to ensure that both lower and upper-tier development charges are combined (e.g. York Region and Vaughan) when comparing with a single-tier municipality like Toronto or London.

These charges are paid for by the developer, typically when they obtain a building permit, though in some cases development charges must be paid months or even years earlier when development approvals are obtained. Because the developer often does not receive revenue on a project until completion, those development charges usually must be debt financed through construction loans. The cost of development charges, along with the accrued interest, are incorporated into the cost of building housing in the same manner that the price of drywall or an hour of an electrician's time is. Those costs are incorporated into the final price of the home and, as such, are subject to GST, PST, and land transfer taxes.

Geography plays a vital role

Development charges within a municipality can also have different geographical scopes regardless of its tiered structure. For example, Markham has both 'municipal-wide' and 'area-specific' development charges. Municipal-wide DCs are meant to pay for infrastructure that benefits a very wide geographic range, while area-specific, as the name suggests, is for infrastructure that only benefits a particular set of neighbourhoods.

Determining what is municipal-wide and what is area-specific is often subjective. The DCA provides no clear definition or direction other than an acknowledgement of a difference and a requirement to consider whether infrastructure is municipal-wide or area-specific.

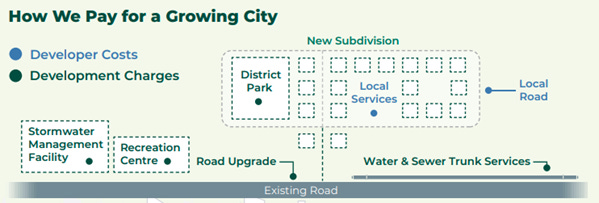

Hyper-local infrastructure is not part of development charges.

What DCs don't pay for is anything hyper-local to a new development. DCs may pay for new walking trails on either a municipal-wide or area-specific basis, but they don't pay for sidewalks to be included in a new subdivision that may connect to the new trail. Those sidewalks are the responsibility of the builder/specific home buyers to pay for; not all buyers of new homes put their money into the various pools of DC funds.

Determining what is local or development charge eligible can sometimes be set out by what are called local service policies (LSPs). For example, an LSP can state that roads below a certain width are considered local; if a builder includes them in their development, they aren't eligible to receive funding from DCs. Like all things DCs-related, it is possible for one group to unfairly pay for infrastructure that benefits others if LSPs aren't scrutinized and set properly.

In their development charge pamphlet, the City of London provides a helpful illustration showing that developers are required to pay for local services and local roads in addition to, and separately from, development charges.

Figure 1. Development Charges vs. Developer Costs

It's about averages…

Municipal-wide DCs are typically charged based on a per-home type. For example, there are different charges based on whether the home is a single detached or a 2-bedroom apartment. The reason for this is that development charges are calculated on a 'per person charge,' which then typically gets translated into a unit-type charge based on the assumed average number of people that homes of that type will have. For example, if, on average, single detached homes are expected to have 2.5 people, then all single detached homes built will be charged proportionally to this average.

…though sometimes it's about land

For some services that relate more to how much land a housing type uses, like stormwater facilities and the permeable surface (or lack thereof) of potential development, DCs can be determined based on a per-hectare basis. Typically, this applies to places with new subdivisions, which is why this type of charge is mostly found in area-specific DCs. Per-hectare charges are based on highly situational circumstances and, therefore, are not widely used compared to charges based on a per-unit type.

Development charges apply to more than just housing

DCs also apply to non-residential uses like offices, industrial, and commercial plazas. The charges for these uses are determined similarly to those for residential, but they are applied based on the number of jobs per square foot/metre of space instead of people per housing type. In some cases, municipalities provide reductions or full exemptions to incentivize certain forms of non-residential development.

Development charges are supposed to only pay for growth-related expenses

Development charges can only be collected for 'growth-related infrastructure’. The money collected is meant only to cover the cost that new housing creates and not benefit existing residents. However, while the process for calculating development charges is well defined, the assumptions that need to go into the formula can be highly subjective and lead to outcomes where the money being collected can easily benefit existing residents or discourage new homes. And, if set improperly, development charges can be used as a tool to redistribute resources from new homebuyers and renters to existing residents, or from new homebuyers and renters to commercial developments.

Also the definition of a growth-related expense can be pretty loose

What is considered allowable 'growth-related' infrastructure and what is not has varied greatly over the last two decades. Currently, development charges are allowed to be collected for 21 unique services and items outlined in section 2(4) of the DCA. Some of these services have straightforward connections to new homes, like water and wastewater infrastructure, while others have a less obvious connection to housing growth, like long-term care (LTC) homes and Waterloo's airport, both of which are specifically mentioned in section 2(4).

Putting it all together

Municipalities can choose to collect DCs for anything permitted in the DCA. However, this does not mean that development charges are necessarily the best way or most appropriate method of paying for infrastructure or that infrastructure has any real connection to the costs imposed by new homes.

The numerator and the denominator

While there are many moving parts and things to consider with development charges, unlike other municipal housing taxes, which are determined based on even more complicated and convoluted formulas that can vary significantly from project to project, DCs are relatively straightforward. Rates are outlined in schedules set by housing type (single-detached, townhouses, apartments, etc.). Of all the municipal charges, DCs are also typically the largest item of the lot.

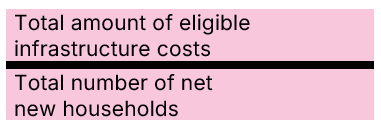

The process of setting development charge rates is complex but ultimately boils down to a single numerator and a denominator.

Figure 2. Development Charge Numerator and Denominator

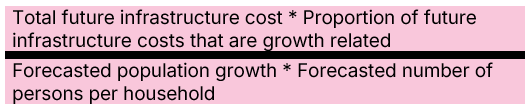

Though, to better illustrate the underlying math, we can split each of the numerator and denominator into two components:

Figure 3. Development Charge Numerator and Denominator (Dual Component)

Because none of these four components are perfectly known quantities when the calculation is made, municipalities are forced to make various assumptions and estimations about each. However, since these per-unit development charge calculations are based on a series of assumptions, municipal governments can substantially increase or decrease development charge rates by tweaking the underlying assumptions.

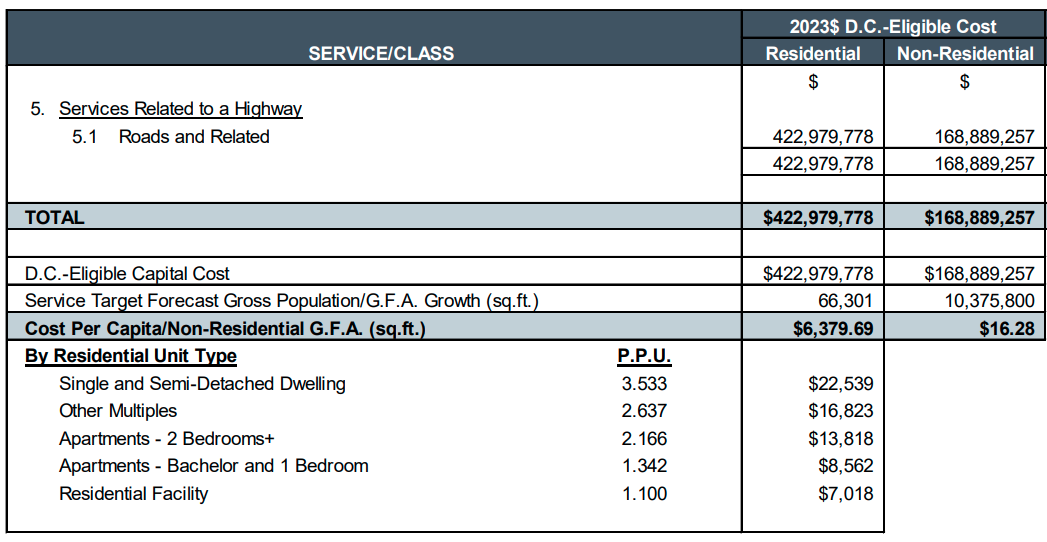

The City of Hamilton’s 2023 Development Charges Background Study provides a tangible example of the phenomenon. Over the planning period, the City is forecasting $592 million in eligible road expenditures, of which $423 million will be placed on residential development charges, with the remainder on non-residential. It is forecasting population growth of 66,301 persons, giving a per-capita road development charge of $6379.69. This is then allocated to each form of development based on the forecasted persons per household, with single-detached and semi-detached forecasted to have 3.533 persons per household and 1-bedroom apartments having 1.342. This then leads to a road development charge of $22,539 for single-detached homes and $8,562.

Figure 4. Development Charge Calculation Example – City of Hamilton

The final figures in our Hamilton example, as with all development charge calculations, are a function of the underlying assumptions.

Development charge rates are highly dependent on four underlying components:

Total infrastructure costs: Municipalities need to estimate the cost of all the roads, libraries, transit, etc., that will be built over the planning horizon. Changes to estimates on how much a piece of infrastructure will cost or whether it is likely to be built at all impact the final estimation. Burlington was able to lower development charges by removing from the calculation infrastructure projects that were unlikely ever to be built, as outlined by the Deputy Mayor.

The eligibility proportion of future infrastructure costs: Not all infrastructure costs are borne by development charges and are thus "eligible" to be included in the calculation. Infrastructure paid for by grants from other orders of government should be ineligible, or at least the portion that those grants cover, along with the proportion of infrastructure that benefits existing residents (that is, infrastructure that is not "growth-related"; planners call this proportion of infrastructure costs "benefit-to-existing"). However, determining how much of a new soccer facility is growth-related and how much benefits existing residents is highly subjective. In the words of Western University's Andrew Sancton, "growth- and non-growth-related expenditures are not clearly separable". Whether you assume 90% of the benefits of that soccer facility will accrue to existing residents or only 50% will yield drastically different results. In the case of that particular soccer facility, the municipality assumed it would have no (0%) benefit to existing residents, placing the entire cost on development charges and grants from other orders of government.

Projected population growth: Suppose the municipality estimates the total amount of eligible infrastructure costs is $100 million. The actual rate that gets charged will depend on how many new residents the city is expecting over the planning horizon (e.g. 10 years). If a municipality lowers projected population growth by half, then their development charge rates double. Forecasting population growth is more of an art than a science, and generally, planners get this wrong more times than not. In the report Forecast for Failure, we show that Ontario growth planners have been systematically under-forecasting population growth, which has the side-effect of making development charges higher than they otherwise would be.

Converting population growth into household growth: Because development charges tax houses, not people, the cost per person estimate must be translated into a housing charge. This translation is based on the estimated average number of people that a housing type is expected to have in the future.

This is admittedly a very simplified explanation of how DCs are calculated; it's clear that even in this simplified analysis, there are already several large assumptions that can lead to drastically different outcomes. These include assumptions on what growth-related infrastructure to include and how much it will cost (numerator), what "benefit-to-existing" ratio to apply (numerator), how much money other levels of government are providing (numerator), how many people you can expect (denominator), and how to translate the number of new people into the number of new homes (denominator).

Cities recognize this. The City of Vaughan is looking to reduce development charges, and a staff report on this proposed reduction illustrates how they can get there by revisiting these assumptions:

To implement a reduction to DC rates, a few approaches are available… Reduce the DC rates by developing a completely new City-Wide DC study (and capital program) based on updated population and employment forecasts.

Vaughan can lower development charges simply by re-examining their nominator and denominator assumptions. This makes it clear that cities can, in fact, lower development charges. Burlington and Vaughan have done it, and Mississauga has followed. They can do this because development charges are ultimately more a function of subjective assumptions and political will than objective analysis.

Download a PDF version of this article below: