The GTA’s Missing Middle: Not Just a Housing Type, but a Whole Generation of Families

The math is clear: families go where family-sized homes are built (r = 0.71).

Highlights

Families are leaving the GTA in search of family-sized homes: Between 2016 and 2021, the City of Toronto, Peel Region, and York Region collectively experienced net outflows of residents to other parts of Ontario, particularly among adults aged 25–37 and children under 6.

Migration patterns track where family-suitable homes are being built: The regions gaining the most residents per capita, such as Lanark, Oxford, and Haliburton, are also those that expanded their stock of ground-oriented ownership housing, with a 0.71 correlation between within-province migration inflows and new supply per capita.

Ground-oriented ownership homes are the family norm: More than three-quarters of couples with children in Ontario live in single-detached, semi-detached, or townhouse-style homes, versus just 52% of other households.

Apartments rarely meet the needs of families with multiple children: Few apartment units in Ontario have three or more bedrooms, making ground-level homes virtually the only ownership option for households with multiple children.

Policy is failing to plan for families: By ignoring the shortage of child-friendly, ownership-oriented housing, provincial and municipal plans underestimate future GTA outmigration and undermine Canada’s stated commitment to adequate housing for all families.

Over the past twenty years, families have been increasingly leaving Toronto, moving to other parts of the province (a phenomenon outlined in the piece The Slow-Motion Exodus: How GTA Outmigration Became Ontario’s Defining Trend). While different people leave for various reasons, the primary driver of this migration is young families seeking three-bedroom (or larger) ground-level homes that they can afford.

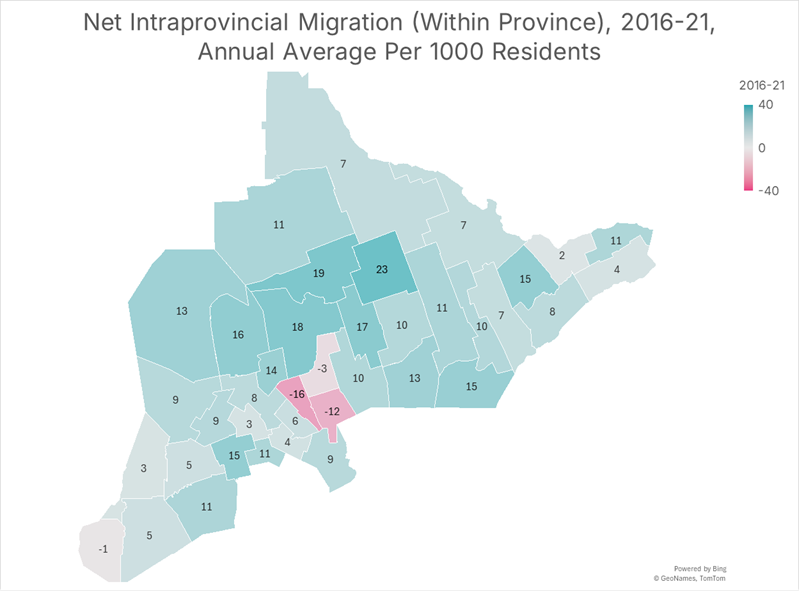

First, let’s examine intraprovincial (within Ontario) migration between census divisions that occurred between 2016 and 2021, the last two years of the census, controlling for population size. In Figure 1, we observe that three GTA census divisions (Peel Region, York Region, and the City of Toronto) experienced net outflows to the rest of the province. To be clear, this does not suggest that their populations decreased; those places grew due to several factors, including births and immigration. However, they experienced a larger number of individuals moving out of those communities from other parts of Ontario, rather than moves in the opposite direction from places in the province.

The rest of Southern Ontario, with the exception of Essex census division, experienced net inflows. The largest inflows on a per capita basis were typically found in smaller communities, such as those in Haliburton, Oxford County, and Lanark County.

Figure 1: Average annual net intraprovincial migration per 1000 residents, July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2021, by Southern Ontario census division

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0153-01, Chart Source: MMI.

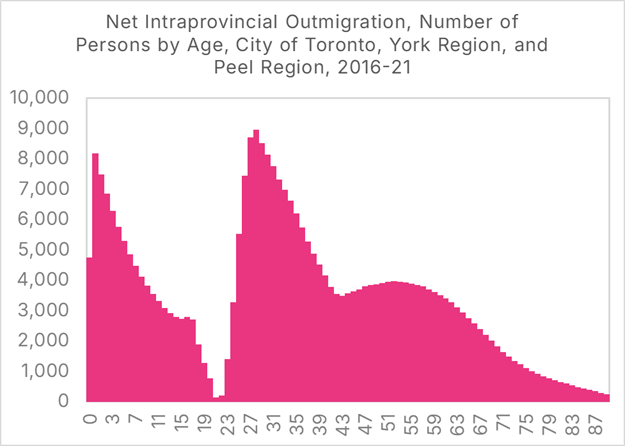

Collectively, the City of Toronto, Peel Region, and York Region experienced net losses of individuals of every age; however, the losses were disproportionately high among individuals between the ages of 25 and 37 and children under the age of 6, as shown in Figure 2. Net losses were smallest between the ages of 20 and 22, due to a large number of young people moving in from other parts of the province to study at a GTA-based college or university.

Figure 2. Increase in ground-oriented ownership homes per 100-person increase in age 15+ population, 2016-21

Data Source: Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0153-01, Chart Source: MMI.

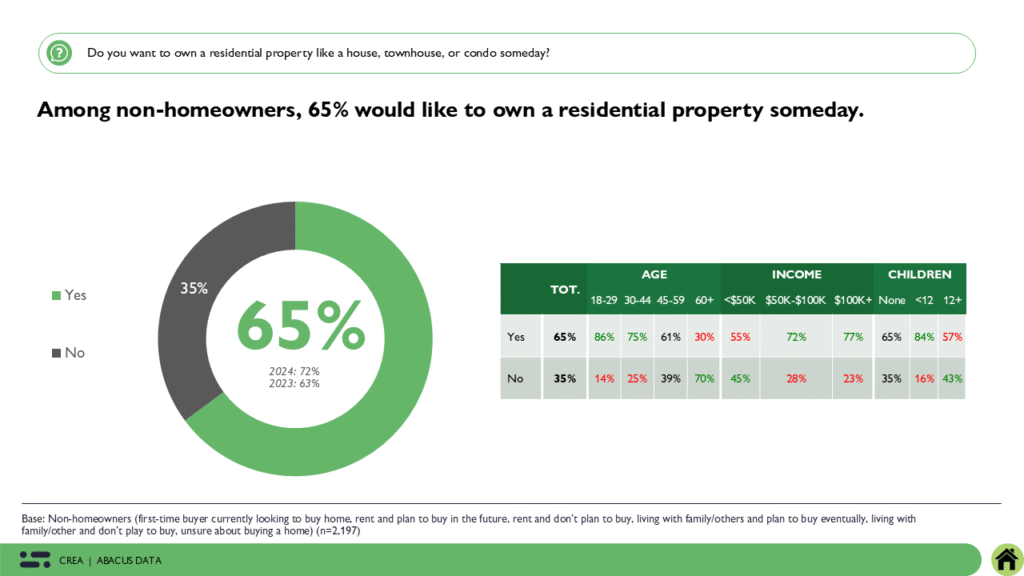

A large, detailed study is needed to determine the relative importance of the various factors causing these moves (if you’d like to support such a study financially, you know where to find us). However, one obvious factor is the lack of attainable homes that families with children under 6, or those planning to have children, can afford to own. According to a recent Abacus poll, three out of four non-homeowners in Canada between the ages of 30 and 44 would like to own a home someday, and an eye-watering 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds share this desire. Among non-homeowners of any age with children under 12, 84% would like to own a home.

Figure 3. Desire for homeownership among non-homeowners by age group

Chart Source: Abacus Data.

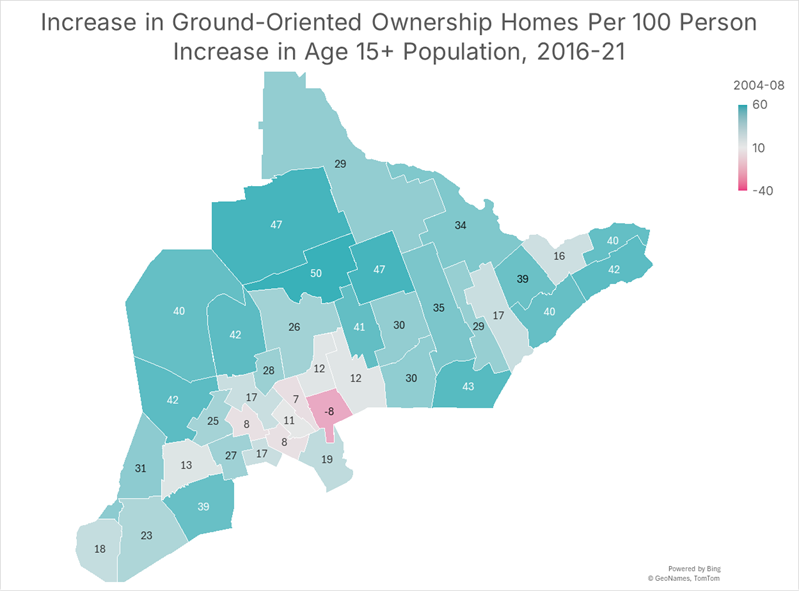

The 2016 and 2021 Censuses contain data on the size of the owner-occupied housing stock for ground-oriented homes (single-detached, semi-detached, and townhomes). If we compare the growth of that stock to the overall population growth during this period and map the results, we obtain a map that closely resembles the one in Figure 1. Relative to the growth of the population of persons over the age of 15, Peel Region and York Region saw a very small increase in the number of ground-oriented homes occupied by their owners. The City of Toronto experienced a net decline of these homes due to demolitions and the conversion of these homes into rentals. Other communities, such as the Northumberland census division, experienced large increases in their ground-oriented ownership housing stock relative to population growth.

For the Southern Ontario census divisions mapped in Figures 1 and 4, the correlation between intraprovincial migration and ground-oriented ownership housing growth between 2016 and 2021 is exceptionally high at 0.71. Multiple causal stories could explain such a relationship, such as families moving to where homes are being built, or homes get built in the places families move to.

Figure 4. Increase in ground-oriented ownership homes per 100-person increase in age 15+ population, 2016-21

Data Sources: Census 2016, 2021. Calculation and Chart Source: MMI

The migration to places with growing stocks of ground-oriented ownership homes should come as no surprise. Over three-quarters of couples with children in Ontario live in one of these homes, compared with 52% of all other households. These figures are calculated for a province where ground-oriented ownership housing is in short supply. If there were no shortage, it is almost certain that an even higher proportion of couples with children would live in this form of housing.

Figure 5. Current housing type by family, Census 2021, Ontario

Data Sources: Census 2016, 2021. Calculation and Chart Source: MMI

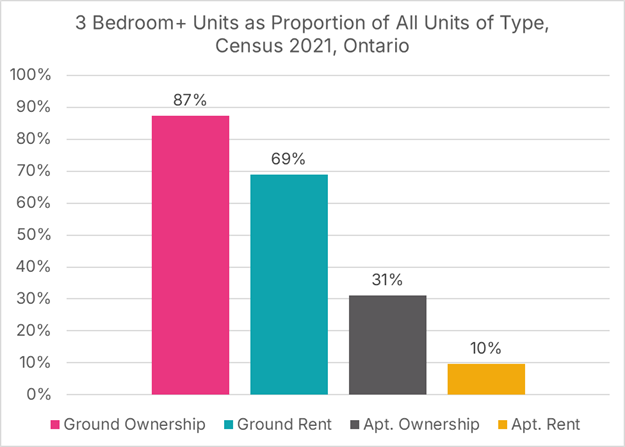

It is possible that what matters here is not ground-orientation, but rather the number of bedrooms in the home; of course, it is possible that both matter. However, if a family wants to own a home with three or more bedrooms (because they have, or plan to have, multiple children), a ground-oriented home is nearly a necessity, as very few apartment units in Ontario meet this standard.

Figure 6. Proportion of units with three or more bedrooms by unit type, Ontario, Census 2021

Data Sources: Census 2016, 2021. Calculation and Chart Source: MMI

Young families with children, or those planning to have children, want a 3-bedroom (or larger) home that they can own, and they’re willing to leave the GTA to get it. Right now, that three-bedroom home is almost certainly going to be a ground-level home, as Ontario’s inability to build apartment units with three or more bedrooms is largely a regulatory failure, as outlined in reports such as Impossible Toronto, the Blueprint for More and Better Housing and The Mid-Rise Manual.

Ontario’s provincial government refuses to acknowledge the need for more child-friendly housing, and most of Ontario’s municipalities share this stance, leading to population projections and municipal plans based on faulty assumptions. Our communities are underestimating the need for child-friendly homes, underestimating future outmigration from the GTA, not making the necessary zoning and land use changes to create communities that are suitable for children, and making decisions that are fundamentally incompatible with Canada’s acknowledgment of housing as a human right, which requires an adequate supply of homes for all types of families.