The Impossible Trinity that Broke Canadian Housing

Learning that we can't have everything

Highlights

Housing is in crisis in Canada, in large part because governments are trying to simultaneously achieve three objectives: robust immigration, protecting the character of existing neighbourhoods, and preventing the outward expansion of our cities.

This challenge is not unlike the Impossible Trinity in Monetary Policy, where trying to achieve three desirable objectives simultaneously leads to the system’s collapse.

Like with the monetary policy trilemma, the obvious solution to the housing trilemma is to choose two of the three objectives and abandon the third. And like with monetary policy, there are no “right” two to choose from, and each pairing comes with a substantial downside.

Unlike the monetary policy trilemma, the non-binary nature of the three housing objectives does make a balanced approach of all three theoretically possible, but it requires a level of discipline and coordination from Canadian policymakers that we have not seen in the past.

At a minimum, achieving all three requires better and longer-term immigration targets, substantial changes to the building code, uploading some zoning responsibilities to the province, and rethinking how urban growth expansions are conducted.

How might a central banker think about housing policy?

Ever since a former central banker became Prime Minister of Canada, I have found myself thinking about monetary policy, a subject I taught at Ivey Business School for nearly two decades.

There’s a concept in monetary economics called the Impossible Trinity, that there are three properties that are beneficial to countries:

A fixed exchange rate with their largest trading partner(s), to avoid exchange rate instability.

Free capital movement (that is, money can freely enter or leave a country)

Independent monetary policy, so a country’s central bank can respond to economic conditions by, say, raising or lowering the policy interest rate.

The impossible trinity suggests that any attempt to achieve all three objectives will inevitably fail. It will create interest-rate arbitrage opportunities that will be exploited, ultimately causing the system to collapse. Attempts to simultaneously achieve all three have caused multiple financial crises, including the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The lesson of the impossible trinity is that countries can, at best, choose any combination of two objectives, foregoing the third. But there is no single “right” two to pick; the choice of objectives will entirely depend on a country’s preferences and economic context.

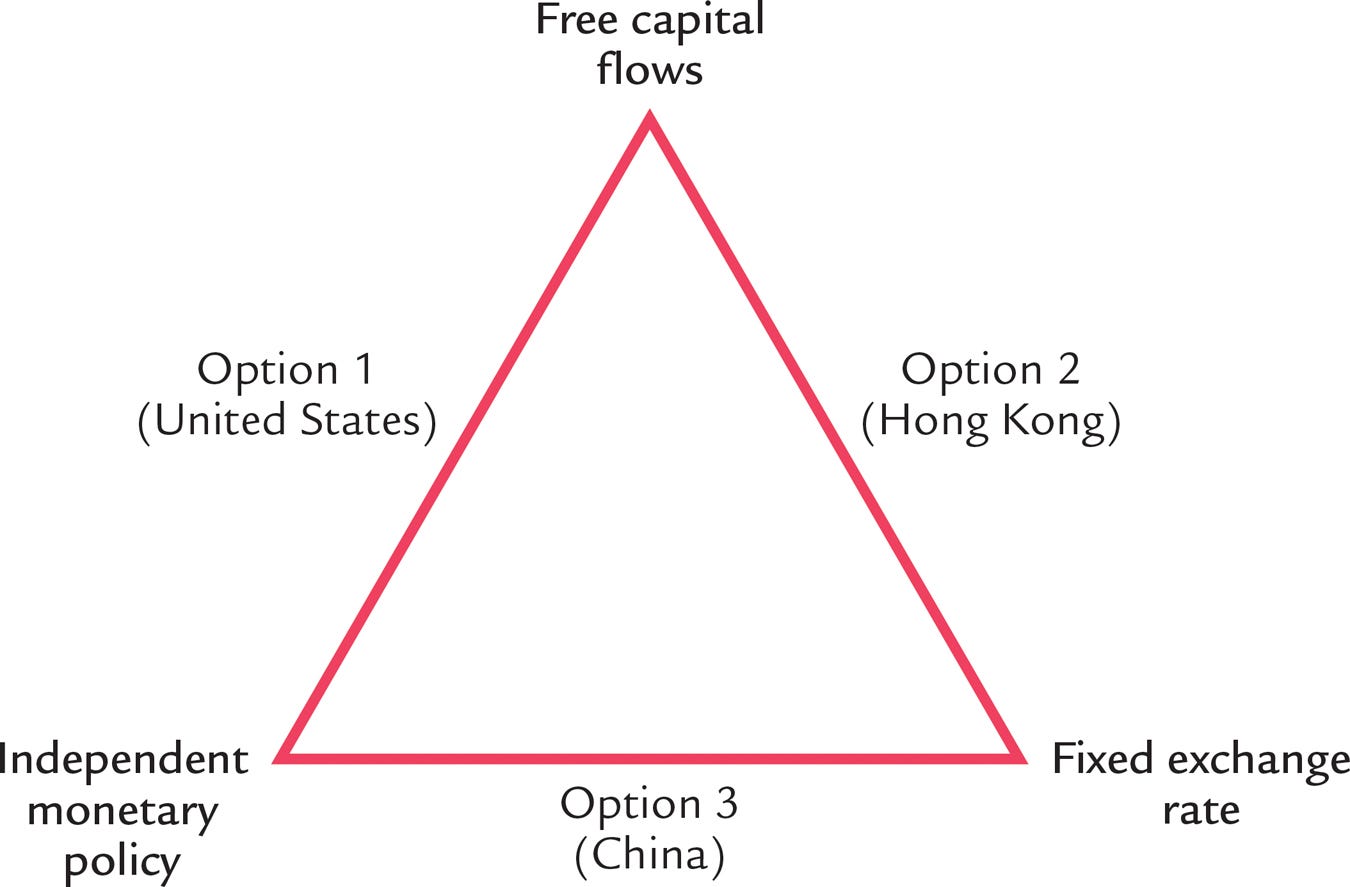

Greg Mankiw’s textbook, Principles of Economics, illustrates this with the following diagram:

The United States has chosen free capital flows and an independent monetary policy; however, it must forgo a fixed exchange rate, which subjects the country to exchange rate fluctuations. China and Hong Kong each chose a different pairing. From 1962 to 1970, Canada had a fixed exchanged rate with the United States, effectively outsourcing large parts of their monetary policy to the U.S. Federal Reserve. Since then, we have enjoyed monetary policy independence and free capital flows, but have been subject to significant fluctuations in our exchange rates relative to the U.S. dollar.

In short, achieving two objectives is achievable, but three is not, and there is no single “right” pair of objectives for every country in every circumstance at every point in time.

The Impossible Trinity of Housing

There is a similar trilemma when it comes to housing. Policymakers across three orders of government, particularly in Ontario, have been trying to achieve three objectives simultaneously.

Immigration. Specifically, immigration rates at, or above, 1% of the existing population, along with rising numbers of non-permanent residents, including international students and temporary foreign workers.

Protect the character (and density levels) of existing neighbourhoods. For example, the City of Ottawa’s 2021 Official Plan references the “character” of existing places 36 different times, and under their proposed re-zoning, they defended a decision to keep 2-storey height limits in many neighbourhoods, by stating that “[t]he emphasis on two-storey developments largely stems from the expectation that new buildings respect neighbourhood character and context.” None of this is unique to Ottawa, as communities across the country are uncomfortable with the idea that existing neighbourhoods may add a noticeable amount of density.

Limited urban footprint expansions to avoid sprawl. Over the last two or three decades, many parts of Canada became understandably concerned about the environmental and economic costs of expanding too far outward. In an effort to prevent that from happening, a series of measures were put in place, including the creation of Greenbelts and tight urban growth boundaries.

Parts of Canada, particularly in southern Ontario, attempted to achieve all three objectives simultaneously, and the system failed. The Ontario housing version of the Asian Financial Crisis led to skyrocketing prices and rents, a substantial increase in homelessness and foodbank use, a growing proportion of adults in their 20s and 30s living with their parents, 20 or more students living in a single home, and Ontarians moving in record numbers to regions with lower housing costs, such as Alberta and Atlantic Canada.

Ironically, Ontario’s impossible trinity of housing lead to increased, rather than reduced, sprawl as “economically induced emigration” occurred, as families were priced out of their communities, moved to a lower-priced community, then commuted back for work and school. We have examined this phenomenon in reports such as The Growth of London Outside of London, and YouTuber Paige Saunders examined the phenomenon in the video Hard Green Belts Have Failed.

Policymakers were not unaware of the tradeoffs here, or the tensions that would arise from simultaneously attempting to achieve all three housing objectives, though municipal governments were often in denial about how quickly Canada’s population was growing, and often failed to incorporate increased immigration targets into their planning.

In many cases, the solutions that governments landed on were measures to facilitate the construction of more high-rise apartments, including both purpose-built rentals and condominiums. Given the underbuilding of apartments, particularly in the 1990s, these units were badly needed, and in many parts of the country, a sufficient supply is still lacking. But given the inherent challenges in building three-bedroom (or larger) units in a high-rise, it caused a massive shortage of family-sized homes. High-rise apartments, by themselves, are not a solution to the impossible trinity of housing.

Policy tradeoffs with Housing’s Impossible Trinity

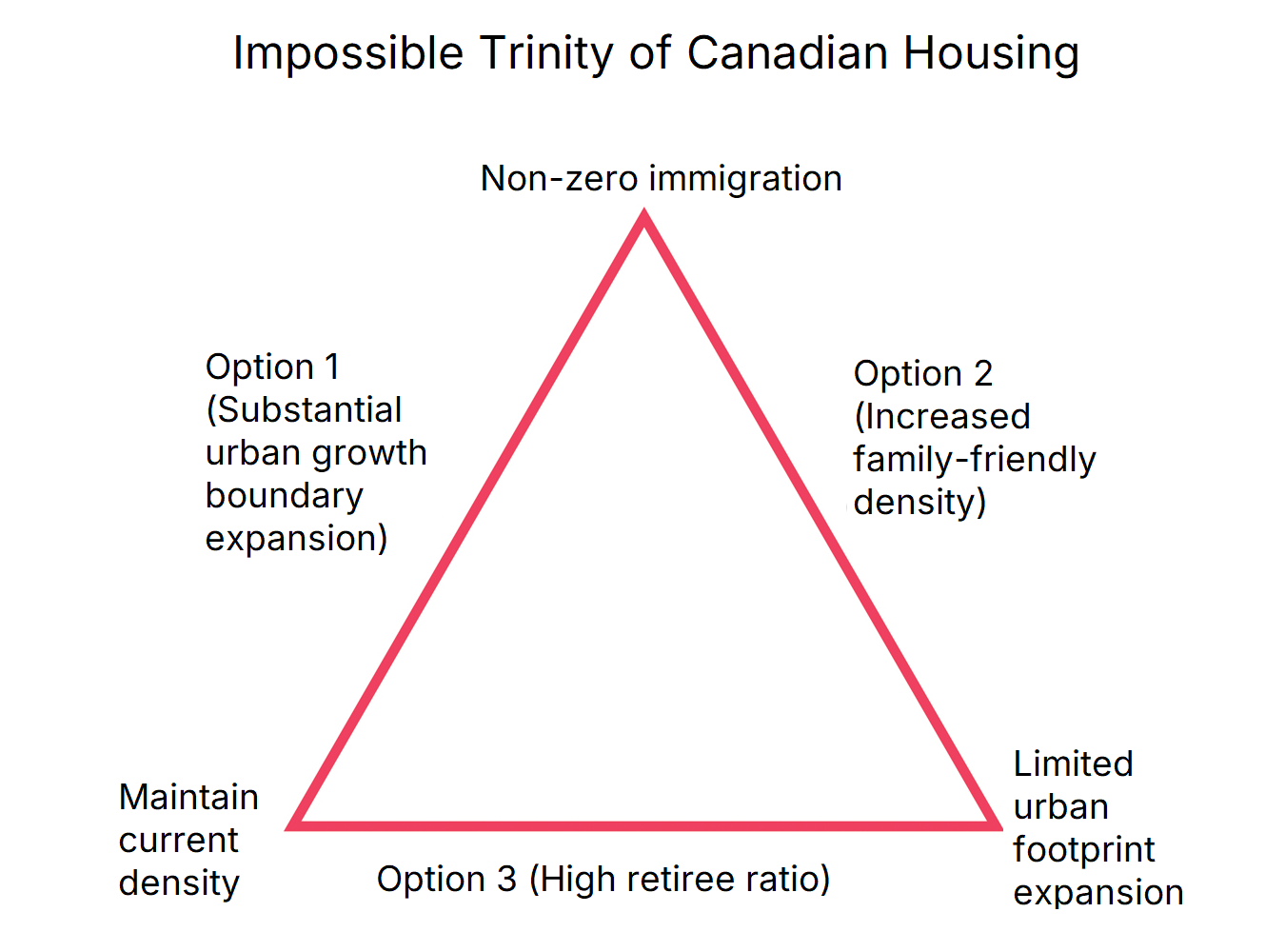

We can adapt Mankiw’s diagram of the monetary policy trinity to one about the housing/immigration nexus:

This trinity model provides us with three options, all with substantial drawbacks.

Option 1: Yes to immigration and yes to maintaining current density. This will require allowing our cities to grow outward, and the greater the rate of immigration, the more cities will need to expand geographically. In Ontario, this would look be a return to pre-Greenbelt, pre-tight urban growth boundaries planning of the late 20th century. Not coincidentally, the late 20th century was also a period when family-sized homes were still affordable in the province. However, this model of growth has both significant environmental and economic costs, as outlined in the SPI report, The Cost of Sprawl. But it is an option.

Option 2: Yes to immigration and yes to limits on outward growth. This will require substantially increasing family-friendly density in existing neighbourhoods. We will need to allow investors to buy up existing homes, tear them down, and replace them with fourplexes, small and mid-rise apartments, and other forms of missing middle housing. This will require substantial changes to building codes and municipal zoning, and substantially lowering development charges and other municipal housing construction taxes on these kinds of units. Environmental Defence’s Mid-Rise Manual gives an outline of the reforms needed, and the Blueprint for More and Better Housing provides dozens of policy reforms to advance this.

At the Missing Middle Initiative, this is our favourite of the three options, but we also recognize it is the option that the general public loves in theory but hates in practice. It requires municipal governments to make changes that are unpopular with the types of people most likely to vote in municipal elections.

Option 3: Yes, to maintaining current density and yes, to limits on outward growth. This option requires further deep cuts to immigration targets, and there is no way around it. It is also quite costly, as it would see Canada’s working-age population shrink while the number of retirees grows. Healthcare and pension expenditures would rise, and the number of taxpayers would fall, forcing increasing tax rates on remaining workers. It would also impact Canada’s social and cultural fabric in a multitude of ways. This is not our preferred option at MMI, but we recognize that it is popular with many, and advocates of this position acknowledge the underlying immigration-housing tradeoffs that many policymakers and the public do not.

What about the balanced approach?

The obvious objection to the impossible trinity formulation of the problem is that the three objectives of housing are less binary than the three objectives of monetary policy. Immigration targets are not binary, and housing needs are different if our population grows by 250,000 persons a year or 1 million a year. Urban growth expansion is not binary; urban footprints could grow at varying rates. Maintaining current density is not binary; there is a difference between a three-storey and a four-storey height limit in existing neighbourhoods.

In short, can’t we do a bit of everything, thus avoiding the trilemma?

The short answer is yes, though it would require substantial changes to our planning. Ontario has been taking the “balanced approach” for the past two decades, and it’s been an unmitigated disaster.

The challenge with adopting a balanced approach mindset is that, without strict discipline, it devolves into policymakers simply refusing to acknowledge trade-offs or make tough choices.

Appealing to a balanced approach also leads to substantial finger-pointing due to responsibilities being split across governments. The impossible trinity of housing is far more challenging than the impossible trinity of monetary policy, which leaves all of the responsibility with the federal government and its central bank. For housing and immigration policy, the responsibilities are split across three orders of government, with no one government controlling all the policy levers.

The existing conception of the balanced approach is a nightmare for small and mid-sized communities in Southern Ontario. They have no control over the policy levers that determine how fast Canada and Ontario’s population grows. They can increase density, which angers their existing voters, or they can grow outward, which can put strain on their finances. And choosing to “grow up” or “grow out” doesn’t solve their local housing crisis anyway; it just leads to more families moving in from larger cities that refuse to make tough decisions. It is a no-win situation.

In short, a balanced approach requires far more coordination across governments and far more discipline than governments have been willing to show.

What would a coordinated, disciplined, balanced approach look like?

In short, a balanced approach requires far more coordination across governments and far more discipline than governments have been willing to show. We would need to coordinate all three goals:

Immigration. Targets for immigration and non-permanent residency would need to be aligned with our capacity to build homes. Both the federal Liberals and Conservatives have acknowledged this, but neither has yet developed a workable way to do this. In particular, these targets should be set over a five—or ten-year time horizon to give other orders of government, along with the development community, time to plan accordingly.

Density. Building code changes are needed, and some zoning responsibilities need to be uploaded to the provincial government because of the inherent externalities involved when some cities allow increased density but neighbouring cities do not. Japanese-style zoning, where cities can choose from a small menu of options rather than have hundreds (or thousands) of arbitrary zones, is needed. In a Canadian conception, provinces would be the ones setting the standards, though the federal government could influence this with programs such as the Housing Accelerator Fund.

Urban footprint expansion is a tougher nut to crack since it involves not just expanding urban growth boundaries but also building the supporting infrastructure to allow for more housing. The current process of deciding how and where to expand is highly subjective, which creates a highly problematic political dynamic. Perhaps a model where an expansion process is triggered whenever home prices reach a certain threshold? This one warrants further thought and study.

Ignoring tradeoffs does not make them go away

Refusal to acknowledge the tradeoffs in monetary policy was a prime contributor to the Asian Financial Crisis, and the refusal to acknowledge tradeoffs in housing policy was a prime contributor to Ontario’s housing crisis. Once we solve this housing crisis, and we believe we eventually will, hopefully, we will develop the foresight not to repeat our mistakes.