You Can’t Fix Zoning If You Can’t Measure It

What Municipalities Should Be Judged on for Housing

Highlights

Alex Beheshti is leaving MMI, but not without first finishing what he started. He’s got a few things left to say before he departs.

Municipalities are judged on the wrong housing metric. Housing starts and completions reflect decisions made by many actors, not just cities, which makes them a poor basis for municipal accountability.

Zoning determines whether housing can be built at all. A single zoning rule can stop an otherwise viable project, regardless of demand, financing, or labour conditions.

Zoning cannot be measured rule-by-rule, but its effects can. The combined impact of zoning rules is captured by development envelopes, which show what is legal to build on a parcel as-of-right.

Development envelopes are the most direct housing metric municipalities control. They tie accountability to zoning decisions themselves, rather than downstream construction outcomes that cities can deflect responsibility for.

Other planning metrics come after development envelopes. Timelines and rejection rates only matter once zoning allows projects to proceed without discretionary approval.

Development envelopes are absent from accountability debates because they are hard to measure at scale. Zoning bylaws are fragmented, inaccessible, and often not readable by computer software, preventing consistent evaluation across municipalities.

Without measurement, zoning remains invisible and unaccountable. When land-use rules are hard to see or understand, legally permitted housing does not get proposed, and municipalities avoid scrutiny for decisions that block homes.

Before What Comes Next

Earlier this year, I wrote Canada’s Housing Crisis Needs a Map to make the case for a National Zoning Atlas. Neither Mike nor I expected it to gain much traction given how esoteric the concept was, but the piece struck a chord with many MMI readers.

In that article, I suggested that the Atlas could enable more advanced land-use planning analysis and, in turn, better policymaking. It has many potential applications, but one could help the federal government most in solving the housing crisis.

To show how the Atlas enables that analysis, I needed to lay some groundwork first. Unfortunately, before I could accomplish that, I accepted a more senior role with another organization that I’ll be taking up at the start of the new year.

While the decision to leave MMI was difficult, Mike has been generous in supporting the publication of the remaining pieces that build towards the revelation of that solution. That begins with discussing why municipalities are judged on the wrong metric.

We Judge Municipalities the Wrong Way

For municipalities to be correctly judged on housing, the metric used must pass a basic test: Does it reflect the decisions cities themselves make? Housing construction statistics, such as starts and completions, fail this test because, as outcomes, they reflect choices made not only by municipalities but also by other actors involved in building homes.

Municipalities should be primarily judged on zoning, because it determines whether otherwise viable housing can be built in the first place. A development project can have all the financing in the world, but a conflict with a single zoning rule is enough to stop it dead in its tracks.

But zoning itself cannot be measured directly. It’s a planning framework composed of many separate rules that operate together as a system.

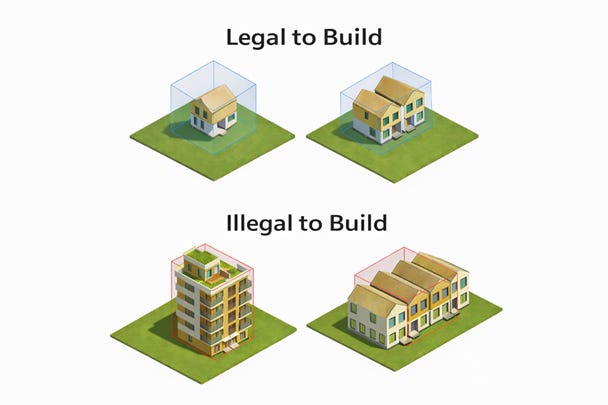

What can be measured is the combined effect of those rules, which is captured by development envelopes. Think of this as an invisible box sitting atop every parcel of land that reflects what zoning makes legal or illegal to build.

The size and shape of that box are determined by how all the rules interact together, including height limits, setbacks, density caps, lot coverage, and other restrictions found in each zoning bylaw’s land-use codes (e.g., R1, R2, R3, etc.). If a proposed housing structure fits within that envelope, it can be built as-of-right. If it exceeds the envelope, it becomes illegal and requires an expensive and uncertain rezoning process.

Figure 1: Example of Zoning Development Envelopes and Compliance

Development envelopes matter as a metric because they tie accountability to the part of housing outcomes that municipalities directly control, something housing starts and completions can never do. Without a metric tied to zoning decisions themselves, accountability collapses into debates that municipalities can always credibly deflect.

Why Development Envelopes Come First

Municipalities regularly make many other land-use planning decisions that influence housing starts and completions. This includes how they set up their rezoning process, as reflected in the length of approvals and the frequency of denials.

There is no disputing that timelines and rejection rates are critical metrics for keeping municipalities accountable. However, in a hierarchy of municipal metrics, they and all others like them come after development envelopes for a simple reason.

The fastest planning approval is the one you never have to apply for. Only when existing development envelopes fail to provide sufficient space for a proposed housing project to fit as-of-right do metrics like timelines and rejection rates matter.

We need zoning to be flexible enough to respond to both housing needs and the range of economic conditions that can arise at any time, if we are going to consistently build enough homes. However, planning administration can never keep up with this if it relies on rigid rules that keep development envelopes small and inflexible, because ad hoc decision-making does not move at the speed of markets but rather at the speed of bureaucracy.

Even the best-run bureaucracies struggle to keep pace with market conditions. With hundreds of municipalities across Canada, a housing planning system that relies primarily on discretionary approvals by individuals in planning departments and city councils cannot respond quickly enough to rapidly changing economic conditions. When judging municipal performance on housing, development envelope zoning matters more than any other metric.

Why We Don’t Currently Use Development Envelopes to Judge Cities

Housing starts and completions are used to assess municipal performance on housing for a practical reason: they’re readily available. By contrast, metrics based on development envelopes do not exist at scale because the information required to measure them isn’t consistently accessible across municipalities. That is the gap a National Zoning Atlas was meant to close.

If the texts and maps in a zoning bylaw can be reviewed, an experienced urban planner can, with some work, sketch out the development envelope for a site. The same task can also be done computationally, and software companies already offer commercial products that can generate development envelopes at scale and speed.

However, both planners and software providers are geographically constrained in where they can operate because complete sets of local zoning bylaws are often inaccessible. In Ontario, this problem is particularly acute. For example, in Toronto, pre-amalgamation zoning bylaws still apply to some properties, yet these are not available online in a format that a computer can read.

Accessing these bylaws is technically possible, but only through slow, fragmented methods. It can require physically visiting a municipal office, submitting a request, and waiting several business days for staff to retrieve parcel-specific information. Cities also frequently provide zoning data only on an individual-parcel basis, often as paper copies or static PDF files that, while digital, are not in a format a computer program can use.

When zoning is difficult to access or analyze, municipalities cannot be evaluated on the decisions they make or held accountable for them. That is why development envelopes, despite being the right municipal metric for housing, remain largely absent from discussions about accountability.

When the Rules Are Hard to See, Bad Outcomes Follow

Ignorance of the law is not an excuse, but governments cannot be ignorant of how they provide access to laws, as municipalities are with zoning data. Land-use rules shape not just housing but also other economic outcomes by defining the boundaries within which municipalities, builders, lenders, and buyers make decisions.

When those rules are opaque and difficult to access, people are forced to act with incomplete information, while municipalities retain discretion to interpret and enforce them without clear culpability. In that environment, bad decisions become more common, not because people are acting irrationally, but because they cannot clearly see what is allowed.

This matters for zoning because visibility shapes outcomes, but not just through accountability. Even if development envelopes are improved, those improvements would have little impact if the people affected by them cannot easily see what is permitted.

People can easily connect with the impact of housing stats and completions because they are so highly visible. Anyone can access this information from the comfort of their own home, which is why experts, news outlets, and social media so frequently cite it. But the issue with visibility and zoning isn’t about tweeting a chart about it. It’s more dire than that.

A property owner who does not know they can legally build a laneway suite or a multiplex is unlikely to do so, even when the zoning allows it. When zoning is hard to access or understand, legally permitted housing doesn’t get proposed, and reforms fail quietly without producing more homes. While transparency in zoning is essential for municipal accountability, its visibility is also critical to improving housing outcomes by creating awareness.

Why Accountability Starts with Measurement

Municipalities are judged on housing using construction statistics because those numbers are readily available. Zoning decisions are not.

When homes do not get built, cities can easily deflect blame to interest rates, buyers, or homebuilders. Those factors matter because they help explain why housing starts and completions are not entirely within municipal control.

But that list of causes conveniently leaves out the decisions cities make that also shape housing outcomes. Zoning determines what kind of housing can legally be built on a site before any other actor steps onto the stage.

Development envelopes make those choices visible. They show, in concrete, easy-to-understand terms, what a municipality allows to be built and what it blocks.

We are in a housing crisis. We cannot afford zoning rules that quietly block viable homes without being seen. Without measurement, zoning stays invisible, and accountability never attaches to municipalities because nothing forces those decisions into the open for public scrutiny. As the maxim says, you cannot fix what you cannot measure.

A PDF of this article is available below