Built to Fail: Ontario’s New Housing Methodology Is a Blueprint for Shortages

How vague rules, bad math, and misplaced incentives could lock Ontario’s housing crisis in place for decades

Highights

The Government of Ontario is making a number of changes to municipal planning, including requiring that municipalities incorporate the Ontario Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) population projections in planning.

The province has asked for feedback on its reforms. While MMI strongly supports the requirement to use the MoF population projections, the current reforms are lacking and suffer from seven issues.

The proposed methodology perpetuates housing shortages rather than addressing them

Municipalities are given so much leeway to make adjustments that the requirements are merely suggestions

Allowing larger communities to alter their forecasted housing need in subjective and unpredictable ways makes it impossible for smaller communities to plan

Allowing municipalities to reduce housing needs forecasts due to “infrastructure availability and capacity” creates perverse incentives

Population projections should incorporate how land shortages will impact migration patterns

Population projections would be strengthened through increased transparency and sensitivity analysis

Municipalities need more structure when determining the types of homes needed, particularly when it comes to generational turnover

We recommend that the province, rather than individual municipalities, generate and assign total housing needs estimates as a minimum standard.

Our seven thoughts

The Government of Ontario is “seeking feedback on proposed guidance to assist planning authorities with identifying population and employment forecasts and assessing land needs requirements to better plan their communities.” The Missing Middle Initiative took the opportunity to submit comments to the province, which are shown below. The TL;DR version is that MMI recognizes the need for reform, but the current changes do not go nearly far enough, and will cause the province to continue to suffer from chronic housing shortages for years to come.

Re: ERO 025-0844 Proposed Updates to the Projection Methodology Guideline to support the implementation of the Provincial Planning Statement, 2024

The Missing Middle Initiative is grateful for the opportunity to provide this feedback submission. While MMI has supported and continues to support requiring municipalities to use population projections generated from the Ministry of Finance in their planning, the proposed reforms are highly flawed and would lead to a continuation, if not an acceleration, of the housing crisis if implemented as-is.

Here are the seven significant issues we have identified with the proposed reforms, along with proposed corrective measures.

1. The proposed methodology perpetuates housing shortages rather than addressing them

Imagine you have a community with a large, growing, and chronic housing shortage. These shortages would lead to high home prices and rents, significant outmigration to other communities, all of which would be reflected in the data. We would also expect to see:

A higher proportion of adults living in their parents’ homes.

Housing overcrowding, where individuals live with multiple roommates in cramped conditions.

Elevated rates of homelessness.

These phenomena would appear in the data in multiple ways, most notably in atypically low household formation rates relative to communities where there are smaller or no housing shortages. This insight is the backbone of the RoCA Benchmark Model, where deviations in household formation and age-specific headship rates can be used to estimate housing surpluses and shortages.

The province of Ontario is advocating that municipalities adopt a different approach, taking their current local household formation rates as a constant when estimating how many homes are needed to keep this rate stable in the future. In other words, under the methodology, the goal of a community should not be to address the housing crisis, but to ensure that the housing crisis stays at current levels, neither getting better nor worse.

Or, to put it more bluntly: The province’s method inadvertently tells places with high homelessness that they should assume this is an inherent quality of the community that cannot be addressed, and that they should plan to continue being a high-homelessness-rate community in the future.

It is also clear that the province recognizes the absurdity of such an approach, as on page 18 of the update document, they suggest that municipalities “should consider suppressed household formation” in their estimates, which, if done correctly, would address the absurdity of planning to lock housing shortages in amber. But the lack of requirement to incorporate this factor makes “should consider” a synonym for “can safely ignore”, and the province has provided only vague guidance (on Page 20) to municipalities on how they would even incorporate it, if they had a desire to do so.

Instead of using pre-existing local age-adjusted headship formation rates as a starting point, the province should assign target rates to each community (such as those found in the RoCA Benchmark 3.0 Model), which would cause municipalities with large, pre-existing housing shortages to increase their ambition in their planning.

2. Municipalities are given so much leeway to make adjustments that the requirements are merely suggestions

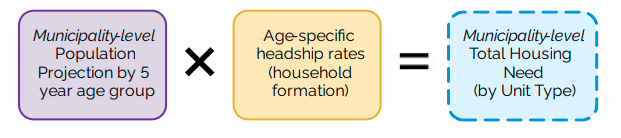

Our high-level summary of the approach in the document is that municipalities should start from the Ministry of Finance’s population projection by age:

Figure 1: Diagram of housing step 1 – calculating housing needs

Source: Province of Ontario

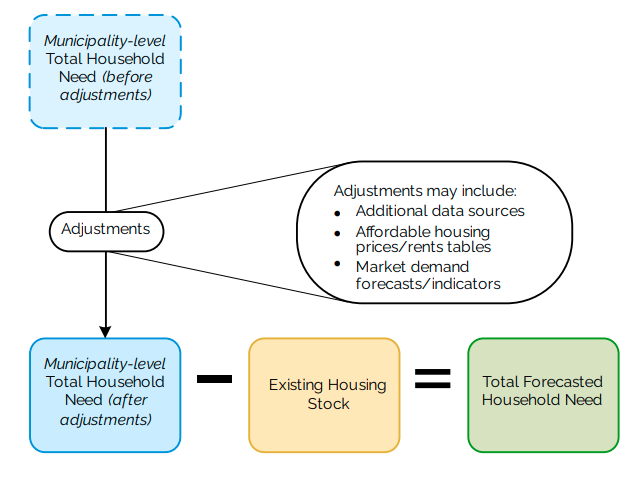

Municipalities then apply various adjustment factors, many of which are completely subjective and chosen by them, which could either decrease or increase their estimate of how many homes the community will need in the future.

Figure 2: Diagram of housing step 2 – developing a housing needs forecast

Source: Province of Ontario

There are no practical limits to the types of adjustments that municipalities can apply during the process, simply that they “should substantiate the adjustment(s) by documenting the evidence and the decision-making process on which they rely”.

In short, municipalities can arrive at any figure they desire for “total forecasted housing need” by taking the results of the (highly flawed) total household need before adjustment calculation and applying a series of subjective adjustments to ratchet up or down to the desired level.

3. Allowing larger communities to alter their forecasted housing need in subjective and unpredictable ways makes it impossible for smaller communities to plan

For many smaller communities across Ontario, over 100% of net housing demand comes from families moving there from other parts of the province. Without such migration, many of those communities would be depopulating due to population aging.

However, if those communities can not predict how much larger, nearby communities will ratchet down, or up, their housing needs forecasts, they will be unable to forecast local demand.

Consider Lanark County in Eastern Ontario, where almost all net demographic-based housing demand stems from either families relocating from the City of Ottawa or from families in other parts of Ontario who could have moved to Ottawa but opt to settle in Lanark instead.

Suppose Lanark cannot rely on the City of Ottawa to plan for the population growth levels forecasted by the Ministry. In that case, it has no means of reasonably estimating future demand.

Of course, Lanark can choose to ignore this factor and plan using population growth estimates generated by the Ministry. However, suppose the City of Ottawa decides to underplan. In that case, the spillover demand will inevitably shift elsewhere, and there is no mechanism in place to require municipalities to adjust their ambitions in proportion when others reduce theirs.

The amount of flexibility that municipalities are given in planning generates high levels of externalities for neighbouring communities, which the proposed plan does not consider.

4. Allowing municipalities to reduce housing needs forecasts due to “infrastructure availability and capacity” creates perverse incentives

One of the adjustment factors listed in the proposed update is “infrastructure availability and capacity,” which suggests that municipalities can reduce their estimated total forecasted housing need based on infrastructure limitations.

On the surface, this appears sensible, but it creates a perverse incentive whereby a municipality that does not want to do its fair share in supporting population growth could underinvest in infrastructure to slow growth, particularly infill development.

5. Population projections should incorporate how land shortages will impact migration patterns

There are some limitations, however, that some municipalities cannot overcome, with the most notable being a lack of land. In the recent MMI report, Families on the Move: 670,000 More Households in Eastern Ontario by 2051, we show that the GTA, particularly the City of Toronto, is unlikely to build enough three-bedroom (and larger) homes to satisfy families with children (and families that would like to have children). As such, outmigration is likely to accelerate, which would cause the GTA to underperform their population projections, and communities in Eastern Ontario to grow faster than the Ministry of Finance projects.

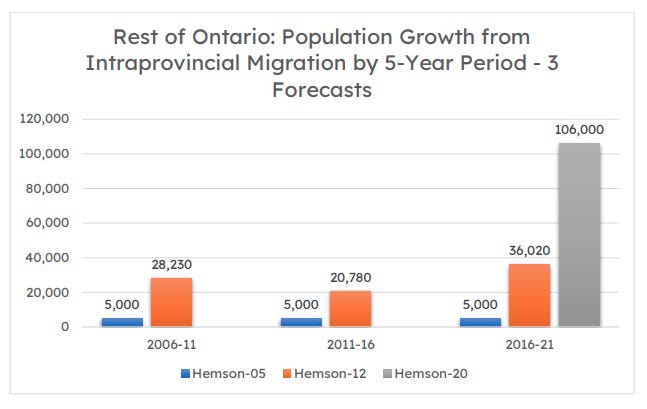

This finding should not come as a surprise, as the January 2022 report Forecast for Failure showed that for the past 20 years, provincial population projections have consistently underforecast the number of families that leave the GTA for other parts of Ontario.

Figure 3: Intraprovincial migration, Ontario, forecast revisions over time

Source: Forecast for Failure

There is a two-sided relationship between population growth and housing growth; the growth of the population helps determine the growth of the housing stock, but the growing of the housing stock also helps determine population growth. As we recommend in “Families on the Move, " the Ministry of Finance’s population projection model should be adjusted to incorporate better “drive until you qualify” migration patterns.

6. Population projections would be strengthened through increased transparency and sensitivity analysis

One challenge that municipalities and analysts have in assessing the quality of the Ministry of Finance’s population projections is that the model is a “black box”; there is no way for outsiders to understand the model or to assess the validity of its assumptions. Furthermore, because the releases from the Ministry fail to include components of population growth data at the census division level, there is no way for outside analysts to assess the quality of intraprovincial migration estimates.

The Ministry of Finance should provide more fulsome data in their releases, including the projected component of population growth, by age, and data for each of Ontario’s 49 census divisions. Ideally, the Ministry should make its model open source, enabling analysts and municipalities to conduct sensitivity tests and scenario analyses. This would allow them to understand the impact of potential future policy changes, such as immigration targets.

7. Municipalities need more structure when determining the types of homes needed, particularly when it comes to generational turnover

Finally, we should recognize that municipalities must not only estimate the number of homes needed but also their type. To do this, they must make a number of assumptions, including (but not limited to) assumptions around “generational turnover”, the rate at which seniors leave their larger three-bedroom homes and move into something smaller, or leave the community entirely.

Municipal governments across Ontario have consistently overestimated the rate of generational turnover and the rate at which seniors will downsize into smaller homes, which causes them to overestimate the number of larger homes that will enter the market and underestimate the number of larger homes that must be built to keep up with population growth and demographic demand.

The province should mandate the use of a set of assumptions for generational turnover, such as those in the RoCA Benchmark 3.0 Model, and regularly audit the results to determine whether they are over- or under-forecasting the rate of generational turnover of larger homes.

Final recommendation

While many of these reforms are moves in the right direction, the amount of leeway that municipalities are given and the failure to ensure that municipalities address pre-existing housing shortages will ensure that Ontario’s housing crisis persists for decades to come.

Instead of allowing municipalities to provide their own total housing needs estimates, these should be generated by the province and assigned to municipalities as a minimum standard. Municipalities that wished to grow further could choose to base their planning on estimates that exceed those provided by the province, but municipalities would not be permitted to adopt lower figures. In this way, the province could ensure that everyone in Ontario has a safe, comfortable, attainable place to call home.

The submitted letter can be downloaded here: