Development Charges: 10 Things You Need to Know About Housing Taxes in Ontario

Demystifying a complex contributor to the housing crisis

Development charges and other municipal housing taxes in Ontario are complex, so they are easy to disregard. In this installment of Development Charge Deep Dive Day, we provide ten reasons why we should care about them and why deep reforms are needed. And if you prefer your articles in PDF form, click on the download link on the bottom of the page.

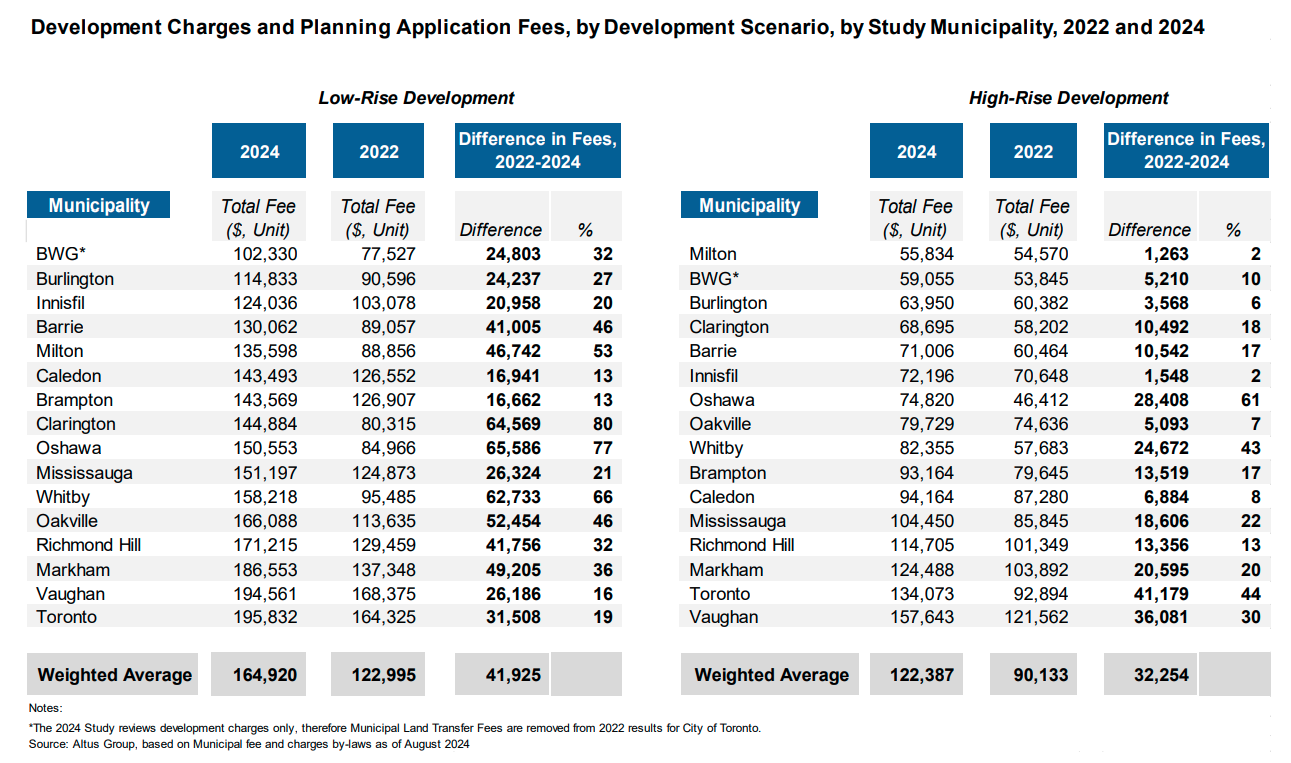

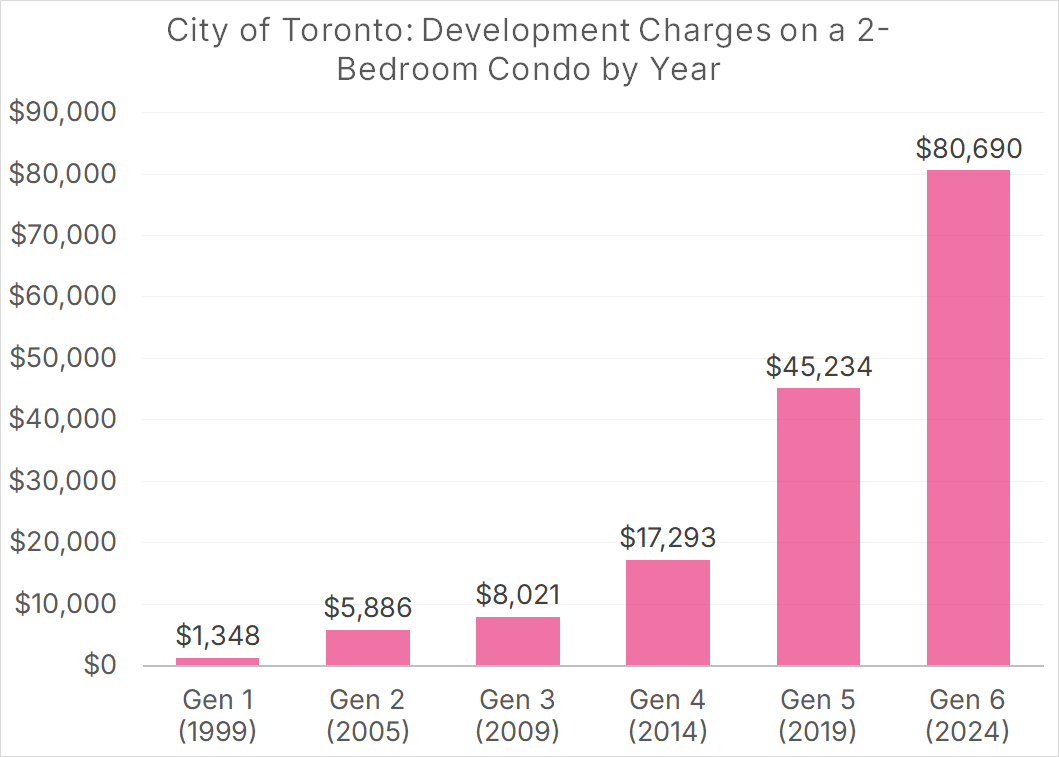

The alphabet soup of housing taxes that Ontario municipalities impose on housing, from development charges (DCs) to community benefits charges (CBCs) to parkland dedication fees, raise the price of even a modest home by over $100,000, pricing out the middle class. This is a relatively new phenomenon; today, development charges alone on a two-bedroom apartment in the City of Toronto are over $80,000 a unit, whereas 25 years ago, they were less than $2,000. There is no world in which 4000% increases are sustainable or justifiable.

Add on top of that provincial and federal taxes on new housing, like the PST and GST, and it becomes clear how housing became unattainable for middle-class families in much of Ontario.

Development charges and other municipal housing taxes are complex. Over the coming months, we will publish a series of pieces that will demystify them and provide additional detail on the following ten things that Ontarians should understand about housing taxes.

Ten Things Ontarians Need to Know About Housing Taxes

High housing taxes are a leading contributor to the housing affordability crisis.

High housing taxes are growing at an unsustainable rate.

High housing taxes are substantially greater in Ontario than in the rest of Canada.

High housing taxes reduce the supply of housing.

High housing taxes create a tax-on-tax for homebuyers.

High housing taxes are inflated because of phantom projects and other dubious assumptions.

High housing taxes have left billions of unspent dollars.

High housing taxes can be lowered.

High housing taxes are not inevitable because there are fairer and less expensive ways to pay for infrastructure.

High housing taxes pay for more than growth.

Some details about each of the ten points:

High housing taxes are a leading contributor to the housing affordability crisis. A middle-class family with a child needs, at a minimum, a 2-bedroom home. That family may be only able to afford rents that are under $1,800 a month or a condo that is under $250,000. When housing construction taxes are over $100,000 a home, it is simply not possible to provide this family with housing they can afford. To be clear, this is not the only cause of the middle-class affordability crisis, as other factors have caused home prices to become disconnected from wages. But there is simply no pathway to middle-class housing affordability without lowering housing taxes.

Source: BILD.

High housing taxes are growing at an unsustainable rate. In many Ontario municipalities, development charges and other housing taxes have grown by over 10% a year for the last 25 years. In the City of Toronto, they have risen by an average of 16.7% a year for the last decade. This unsustainable growth path will lead to the charges on a 2-bedroom apartment being $4.4 million by 2051, Toronto’s current planning horizon. That is simply unsustainable, as wages are not growing at similar rates.

High housing taxes are substantially higher in Ontario than in the rest of Canada. A study by the Canadian Homebuilders’ Association found that, in 2022, housing construction taxes varied substantially across the country. In their low-rise scenario, Toronto, Markham, Brampton, and Oakville had taxes over $100,000, while Burnaby, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Halifax, St. John’s, Moncton, and Charlottetown each had rates under $30,000.

High taxes reduce the supply of housing. Some housing projects will always be at the edge of viability. Any large increase in costs, from construction costs to interest charges to taxes, will render them unviable, and they will not be built. In the same way that high congestion charges reduce traffic and high cigarette taxes discourage smoking, high housing construction taxes reduce housing construction.

High housing taxes create a tax-on-tax for homebuyers. Development charges are paid for by the developer, typically when the builder obtains a building permit. In some cases, payment may be required even earlier than that, such as in the Halton Region. The developer must then finance those charges between when they pay them and when they receive payment from the buyer, adding interest expenses to the project. Those charges and interests are costs that are incorporated into the final price of the home in the same manner as the cost of a sheet of drywall or an hour of an electrician’s time. The final buyer then pays GST, PST, and land transfer taxes on top of those development charges and interest costs, creating a tax-on-a-tax.

High housing taxes are inflated because of phantom projects and other dubious assumptions. Development charge rates are set by a complex methodology based, in part, on a list of projects that the community plans to undertake. However, often that list contains projects with no reasonable prospect of ever being built, phantom projects the infrastructure equivalent of vaporware. Some municipalities have acknowledged this, with Burlington being able to reduce housing taxes by removing phantom projects from their development charge calculation. A number of other assumptions, such as future population growth and the accounting treatment of land under municipal assets, can also lead to inflated development charges, a phenomenon highlighted in the report The State of Development Charges in Ontario.

High housing taxes have left billions of unspent dollars. As of December 31, 2022 (the most recent date for which data is available), Ontario municipalities collectively had $10.7 billion in unspent development charge revenue, an increase of $3.5 billion in just two years. The combination of high rates and phantom projects has created a pool of unspent capital.

High housing taxes can be lowered. In 2024, both Vaughan and Burlington lowered development charges. Mississauga (as of January 28, 2025) is considering a series of reforms, including cutting development charges by 50% and eliminating them entirely for 3-bedroom apartments. Cities can lower these taxes if they have enough political will, though they will need to prepare for criticism from Mayors and councillors in other cities.

High housing taxes are not inevitable because there are fairer and less expensive ways to pay for infrastructure. Our province and our communities need massive investments in infrastructure, but there are better, less expensive ways to pay for them. Municipal service corporations for water and wastewater, for example, can save hundreds of millions of dollars a year in financing costs alone while still ensuring that “growth pays for growth” through hook-up fees. Keleher Planning & Economic Consulting estimates this could save homebuyers $150 a month by lowering the interest costs related to infrastructure.

High housing taxes pay for more than growth. The merits of “growth should pay for growth” are debatable, but we should understand that housing construction taxes pay for more than housing-related infrastructure. The City of Toronto used one form of housing tax, Community Benefit Charges (also known as Section 37 charges), to pay for renaming Yonge-Dundas Square, and development charges have been used to pay for municipal cemeteries. Regardless of the merits of these projects, they are hardly growth-related infrastructure. But even when these dollars are being spent on housing-related infrastructure, they are often used to subsidize existing homeowners due to how municipalities apply the rules to what is and is not a growth-related expense.

Ontario’s high housing taxes have contributed to the middle-class affordability crisis. Fortunately, there are fairer and less expensive ways to pay for infrastructure. We need all levels of government to work together to reform this badly broken system.