The Development Charge Doom Loop

Thanks to a methodological bug, today's development charge hikes cause future development charge hikes

Highlights

In theory, a provision is supposed to ensure that development charges in Ontario do not grow out of control.

In practice, that provision contains a ‘doom loop’, where increases in development charges increase the cap on development charges, which renders that provision ineffective.

Municipalities can eliminate this doom loop by valuing their assets in development charge studies the same way they do in other reports.

Ontario’s Development Charges Act doom loop

At the Missing Middle Initiative, we’re commonly asked, “How are municipalities allowed to set such high development charges?” The Development Charges Act has a provision, 5(1)4 of the Act, that is supposed to ensure DCs do not get out of control. Unfortunately, that provision contains a doom loop: high housing taxes cause the value of existing buildings to rise, and those higher-priced buildings allow municipalities to increase development charges further.

The mechanism of this feedback loop is complicated, but it relates to how land value assumptions are incorporated into the calculation of development charges (DCs) through a mechanism called the level of service (LOS).

The level of service requirement is supposed to act as a cap on DCs

The level of service, or LOS, is a requirement under the Development Charges Act that creates an upper limit on development charges and is calculated in a municipality’s development charge background study. It’s designed to ensure that new residents' contributions to a municipality don’t exceed those of existing residents.

As our Development Charge primer showed, there’s no single development charge. Each service (e.g., transit, water, etc.) has a separate charge, with the money collected going into a separate reserve fund to be used for that service. For each of these services, a municipality calculates a level of service by calculating the per capita assets of each service.

For example, suppose all the fire assets, such as fire stations, in a municipality are estimated to be worth $10,000,000, and there are 2,000 existing residents. In that case, the level of service is $5,0001 per person.

This $5,000 creates an upper bound on the “fire services” portion of development charges, on a per new resident basis. Translated into a charge by unit, if a new apartment is estimated to hold two people, then the municipality can set a fire services development charge for an apartment unit of up to $10,0002. They can charge a lower amount, if they wish, but they cannot exceed this amount.

But what are fire assets worth anyway?

The level of service formula is a function of the size of the population and the value of assets in a particular category. Getting an accurate estimate for a municipality’s population is easy; obtaining one for the value of, say, fire assets is less so.

To calculate the value of the assets, you average the replacement value of all the assets in a service category, like fire services, over 15 years preceding a development charge background study. In our fire service examples, assets include things like vehicles (e.g., fire trucks), equipment (e.g., fire hoses), and most importantly, buildings (e.g., fire stations).

Buildings typically make up the largest asset value item for most service categories. A building’s value is composed of two parts, the structure value and the land value the structure sits on top of. For an asset like a fire station, which is very rarely bought and sold, determining the value of both the structure and the land can be quite challenging.

One asset, two values

Determining the replacement value of an asset, like buildings, can be quite complicated, as it depends on various accounting assumptions, which can lead to absurd situations where a municipality will give two different valuations for the same basket of assets in different financial documents.

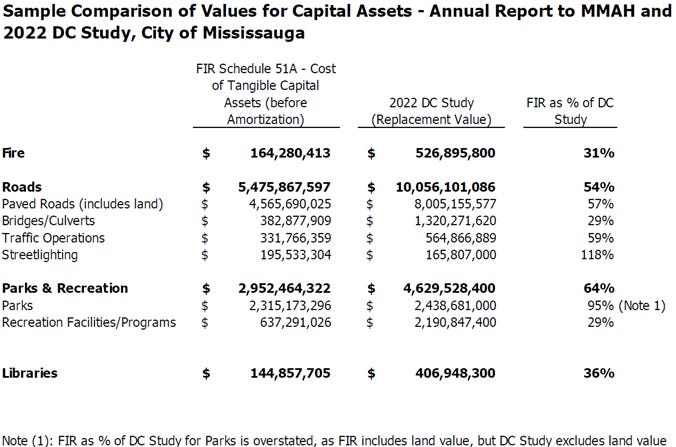

An example of this is how Mississauga values several service categories of assets in their financial information return3 (FIR) compared to the values that appear in their development charge background study. There are substantial differences for all sorts of services, including for fire, where Mississauga claims in their FIR has a total asset value of $164 million, but in their DC background study has a total value of $527 million, as shown by Figure 1.

Figure 1: Asset values for the City of Mississauga

Source: KPEC Consulting

Land value assumptions drive the difference

The difference between the two documents is in how land values are calculated.

In the FIR, the value of land is based on the expense incurred, that is, what the municipality actually paid for the land.

In the development charge background study, the land values are based on estimated market values, that is, what the municipality estimates it could sell the land for now.

As land prices typically appreciate over time, the estimated market value of a piece of land tends to greatly exceed the cost of that land when the municipality acquired it. In particular, because municipal services are often located close to residential areas to serve nearby residents (e.g. libraries, fire halls, recreation centres, etc.), they tend to be on some of the highest value pieces of land in a city.

The estimated market value doom loop

By using estimated market values in development charges, a doom loop is created, which works as follows:

The value of municipal buildings (structures plus land) rises, allowing cities to charge higher development charges.

Those higher development charges raise the price of new homes, slowing their construction and raising the value of existing homes, in the same way that high prices and low availability of new cars raised the price of used cars during the pandemic. The market value of homes, which is a bundle of both the structure and the underlying land, rises.

Municipal buildings, such as fire stations, also rise in value, as the rising market value of other buildings determines their market value.

The value of municipal buildings (structures plus land) rises, allowing cities to charge higher development charges, etc.

The very mechanism that is supposed to prevent development charges from getting too high allows development charges to increase in response to a development charge increase.

There is a solution to the doom loop

To fix this, municipalities could use the same accounting rules in development charge studies as they do in their financial information returns. In that case, the doom loop would disappear, as increases in development charges would not lead to increases in the book value of their assets. This would be a straightforward way to ensure that development charges do not grow to a point where the middle class is priced out of housing.

Download a PDF version of this article below:

10,000,000 / 2,000 = 5,000

2*5,000 = 10,000

The financial information return (FIR) is a report that Ontario municipalities are required to submit annually to the province.