The Housing Trilemma: Why You Can't Afford a Home

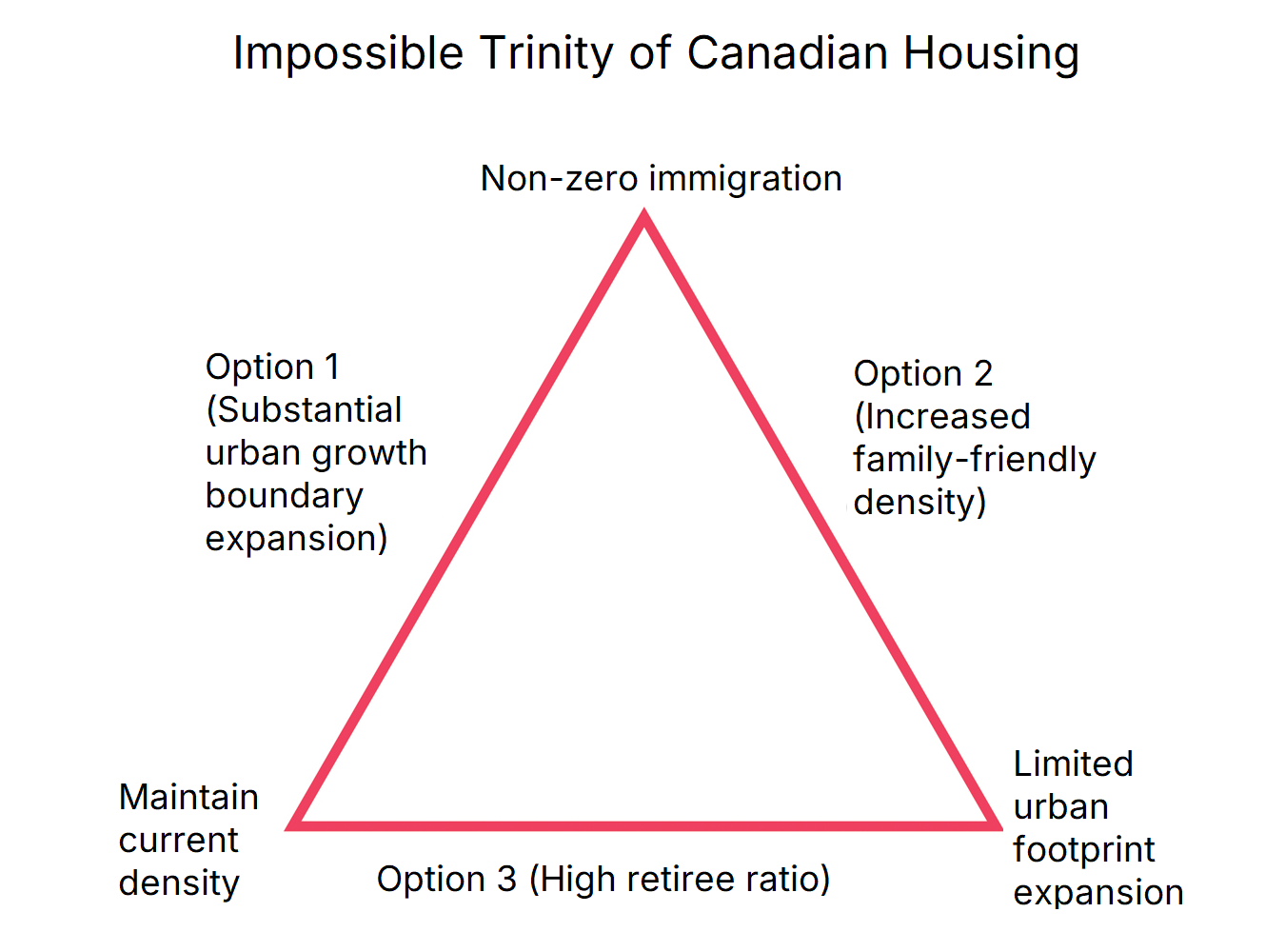

You have to choose two: Robust immigration, protecting the character of existing neighbourhoods, preventing the outward expansion of our cities.

In this episode of The Missing Middle podcast, hosts Sabrina Maddeaux and Mike Moffatt discuss the impossible trinity that broke Canadian housing.

They explore the implications of stagnant neighbourhoods, population growth, and government policies that hinder housing affordability. The conversation delves into the complexities of urban planning, the impact of NIMBYism, and the need for realistic solutions to address the housing crisis.

If you enjoy the show and want to support our work, please subscribe to our YouTube channel. The pod is also available on various audio-only platforms, including:

Below is an AI-generated transcript of the Missing Middle podcast, which has been lightly edited.

Mike Moffatt: So Sabrina, we had a pretty interesting week last week as a reporter asked newly minted Housing Minister Gregor Robertson if he felt that housing prices need to go down, to which the new minister responded, “No, I think that we need to deliver more supply, make sure the market is stable. It's a huge part of our economy.” That generated quite a stir on social media. There are a lot of pile-ons, myself included. But the minister did not back down. He clarified, “that the question I answered was about reducing the price of a family's current home, which for most Canadians, is their most valuable asset.” So, since you're our resident Millennial and our resident future first-time homebuyer, I need to know, what was your reaction to the Housing Minister's suggestion that home prices don't need to fall?

Sabrina Maddeaux: Well, judging by his comments, I might never be a homebuyer because that's essentially what he's telling the young people of Canada.

I mean, in short, he's wrong. He's just so wrong. Prices do need to fall. Like it's common sense, that's the math. If housing is ever going to become affordable.

Mike, you actually did the work on this a while back, breaking down the math. And you found that if home prices in Canada remain the same, and we solely rely on the plan of incomes catching up to restore housing affordability, it could take 20 to 40 years in high-cost regions like southern Ontario, and lower mainland British Columbia for anything resembling affordability to come back.

Now, you keep in mind that millennials are already the older ones in their early 40s, and Gen Z is in their 20s. I mean, you're talking about shutting entire generations of Canadians out of homeownership - affordable homeownership at that point - which should be an absolutely non-starter idea.

Continuing what he said, young people also don't want to just live in government-funded social housing. Young professionals and middle-class workers with jobs who work hard, want the dream and opportunity of homeownership. They want choice. So if he's truly saying the plan is to make younger generations permanent forever-renters, there seems to be no further thought about the financial and social implications of that.

How do we have the same economic opportunities as Baby Boomers had? How do we save for retirement? How do we actually grow families? Not to mention the disenfranchisement that comes with not being able to buy into an economic system. So that's a dangerous idea, really.

But even if, for a second, we say that young people did want to live in mass-produced-government-affordable housing, even if - and I don't believe the government has the capacity to do this. But if it were built at the scale it would need to be to provide widespread affordability, market values would still be impacted. You can't just build all these rentals that would be affordable for Millennials to live in and then not have it impact the private rental market or housing values in general. Like, you can't have it both ways. The math doesn't math.

So overall, his comments were massively discouraging. And it really felt like we were back to a few years ago in the early Trudeau years of not saying the words “housing crisis” and certainly not acknowledging that prices, yes, do need to come down. And we're just in a world of denial and magic math.

So, I know a lot of younger Canadians, in fact, anyone who cares about housing, was really discouraged to see those comments. And let's hope they were just a rocky start in a media flood. Because if that's the actual policy and plan the new Carney government is planning to move forward with, there's not going to be much hope for affordability in this country anytime soon.

But this also raises the obvious question of how did prices get so out of control in the first place? We've had a number of pieces here at the Missing Middle that dive into this question, including when you wrote The Impossible Trinity that Broke Canadian Housing, and we'll link to that in the show notes. Mike, what exactly is the “Impossible Trinity”?

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, so it's one of the things that has broken the housing market. And, to your point, it is broken. When I hear the Housing Minister say that: we're going to keep prices flat, and eventually, things will become affordable again. Well, that means that my daughter, in grade eight, we'll have to wait till she's 50 to buy a home, which is completely ridiculous.

So to this question of how did the prices get out of control? There's a number of factors. We can look at a variety of things like interest rates and the money supply, all kinds of things. So this isn't meant to be a theory of everything. The impossible Trinity, for instance, doesn't really explain the US subprime home crisis and that kind of thing. But, I think it explains a lot of what's happening in Canada and has happened in Canada over the last 20 years. So it's not a theory of everything. But it's a theory of a lot of things.

And here's what it is: that governments across Canada are really trying to simultaneously accomplish three things that are fundamentally incompatible. The first is that they're trying to stop cities from growing out. They're trying to stop sprawl, they want to stop cities from growing bigger and bigger and bigger.

The second thing that they want to do is keep existing neighbourhoods from changing too much. You talk to any municipal politician, look at any municipal official plan, they talk over and over about the character of the neighbourhood. ‘We can't change the character of the neighbourhood, we have to kind of keep things essentially frozen in amber.’

And the third thing is we want population growth through immigration, and also international students and that kind of thing.

This is challenging for governments, in part because no government owns all three of these pieces. So, for municipal governments, and a little bit for provinces, they really can only control the last two pieces of the trilemma. The ‘keeping neighbourhoods from changing too much’ and ‘stop cities from growing out’, because they basically have to treat population growth as something outside of their control.

So cities have a choice to make. I mean, they can either allow cities to grow out, or they can allow cities to grow up in a kind of gentle density kind of way. But they're really choosing to do neither. And the country as a whole really has to choose to do two of these three things. They can't do all three.

Sabrina Maddeaux: So are there any places that are doing two of those three things right now?

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, I think there are. So there are places that aren't overly concerned about places growing out. So, Saskatchewan, for instance, Regina, Saskatoon, they don't spend a lot of time being overly concerned about the city growing out. I mean, there are concerns, but it's not something they’re hyperventilating about.

Cities in Texas have grown out, but they are increasing density as well. There are some good measures there. But historically, a lot of these cities in the US south really haven't worried that much about cities growing out.

They say, okay, people need homes, and this is the way to do it.

And even if we look in Ontario, I would say before 2004, we didn't really worry that much about cities growing out. But then 2004, 2005, we had the growth plan, we had the Greenbelt - the province really started to worry about these things. And that worked a little bit in some areas where populations didn't grow all that much, because that's the other third part of the triangle. If your population is not growing that much, then you don't really have to worry about out versus up.

So think [about] Atlantic Canada. Before COVID, they didn't really have to think about this up versus out thing very much because they weren't growing all that much.

I often hear that housing has been in crisis since 1980, or whatever. But if you look at southwestern Ontario, housing affordability didn't change much at all between 2004 and 2014. Homes were affordable in 2004, they were affordable in 2014. And in fact, parts of southwestern Ontario actually got more affordable. Think of Chatham-Kent and Windsor, mostly because of the decline of manufacturing and so on.

So we've seen places do two of three, right? We've seen places that either didn't grow their population or allowed the city to grow out. Allowing the city to grow up is less popular in North America, but we have a lot of places in Europe and Asia, we can point to. And that's the other thing, you have a lot of cities, particularly in Europe, that are still relatively affordable because they've been allowed to densify.

And I think this gets us to the issue in southern Ontario in particular, when the province enacted the growth plan 20 years ago, they didn't allow the cities to densify, right? So we couldn't grow up, we couldn't grow out. And then once our population really started growing across the province in 2015, the triangle hit, and we got prices that are completely out of control.

Now, I think they would dispute that. [Cities and provinces] would say, ‘No, of course, we're allowing cities to densify.’ They might agree with the logic of the triangle, but they say, ‘you're being a little unkind, we are trying to get density. It's unfair to say that we're keeping these neighbourhoods frozen in amber.’

I would tend to disagree. I would tend to say that municipalities and provinces have this nasty habit of enacting what I call Potemkin reforms…like they look good on paper, they look like they're doing something, but they don't actually accomplish anything substantive.

And there's a really good example in your neck of the woods of the GTA, around fourplexes in Etobicoke. So, can you walk us through what's happening there? Because I think it's a really good example of cities claiming to legalize density, but not actually legalizing density.

Sabrina Maddeaux: It's a really good example of all levels of government saying they want to solve housing affordability, but then not really dealing with the realities of solving housing affordability. And this example in Etobicoke is perfect, because it represents how hard it is to actually build more housing, even when the rules imply it's allowed.

So what happened in Etobicoke is that a developer wants to replace one single-family home on Kipling Avenue with two fourplexes, eight family-sized units over 1000 square feet each, near transit. No parking to keep costs down, [and] these units could have sold for 700,000 to $800,000, which is way less than the typical $2.5 million for a new, single-family home in that area.

So this sounds like the ideal missing middle housing we've been talking about, and that politicians say they want, right? But not so fast, because the local committee and appeal body said “no” to this development. And this is after the new Toronto bylaws came in in spring of 2023, which was intended to make multiplexes, like fourplexes, easier to build across the city, including in suburban areas.

So why did this happen? It's a story as old as time these days. The neighbours freaked out, the development was too tall, too big, no parking, too much traffic, will ruin your neighbourhood’s character - 14 objection letters piled in with some calling it “a monstrosity”. And the city's process, unfortunately, let these complaints win, because the project needed minor tweaks or variances, which then allowed NIMBYs to challenge it, and the committee to ultimately veto it.

So this is the problem: Toronto's new rules say they want fourplexes to solve the housing crisis, but when push comes to shove, local resistance and red tape stop them cold. And this isn't a one-time story either. Other recent multiplex proposals in Etobicoke have also faced rejection, despite again, the city's goal of encouraging this missing middle housing type.

We actually talked about this recently on the podcast with More Neighbours Toronto founder Eric Lombardi, about how the community consultation process is so broken, it's not democratic. It just incentivizes NIMBYs and people who oppose housing, and have a lot of time on their hands, to make these objections and to stop these projects from being built.

So that's the entire problem. In the headlines, on paper, it sounds like we're making progress when it comes to building supply, but on the ground, nothing is being built and certainly not the type of housing that we actually need. Because the reality is still at odds with the stated goals.

So in our group chat, you've talked about similar issues in Ottawa, where The City is instituting gentle density reforms that sound great, but also might not accomplish much. So, can you break down what's happening there?

Mike Moffatt: Yeah, absolutely. And I don't want to be overly harsh on the City of Ottawa because they are doing some good things.

Right now, the City is updating its zoning bylaw. In part, what it's trying to do is simplify. Go from having hundreds and hundreds of different zones to a more streamlined approach. And there are some beneficial things in there. They're changing parking minimums, they're allowing a little bit more density on major arterials. I think that's good. [It’s] probably not going to help families all that much, or at least families with kids all that much. They're not the most family-friendly locations. But it's something.

But interestingly, one of the things that they're doing is, they have different zones, and they're allowing fourplexes by right, sixplexes by right, and so on. But in the urban and suburban areas close to downtown, they are retaining a two-story height limit. And along with some of the other rules around setbacks and things like that, they're kind of saying ‘that on the one hand you can build a sixplex or whatever, but on the other hand, you really can't because of all these land limitations.’ Again, you can't really build out enough, you can't really build up enough, because they're putting this two-story limit on.

Now, interestingly, once you get way out of the developed area of the city, the area outside of Ottawa's greenbelt, they are allowing three stories everywhere.

So it's this weird thing, where the places that you would actually want to build fourplexes, they're keeping it two stories. At the places that probably wouldn't build any density in the first place, they're saying, ‘okay, you can have three stories.’ So it's a big thing where The City is kind of saying, ‘Yeah, we're legalizing fourplexes, we're legalizing sixplexes, we're going to get all of this density,’ but they've put so many restrictions on it. And in particular, if you look at the zoning map, where the most restrictions are is in the richest neighbourhoods, right? So they're also kind of exempting well-off homeowners from having to deal with densification, right? They're trying to keep these neighbourhoods frozen in amber. And I live in one.

I live in the Glebe, which is one of those neighbourhoods that the city is saying, ‘We're not going to make that many changes. We're not really going to densify it.’ Even though it's a prime area that’s walking distance to Parliament Hill because it's basically a bunch of people who look like me and have my kind of homeowner wealth and income, they would revolt if the city tried, so they're backing off on it.

So it really kind of shows a trilemma, where jurisdictions can claim they want to do all three things. But at the end of the day, they're really not willing to institute the level of densification necessary to make sure that home prices can become affordable and stay affordable.

Sabrina Maddeaux: Yeah, you see the same thing in Toronto. The wealthiest areas that have seen the least development and are still largely just large, detached homes are the ones where we should be seeing more of that missing middle housing. Because they are walkable neighbourhoods, they're close to transit. But it doesn't look like we're going to get much more of that anytime soon, unless we fix the process.

And I really think there's an argument to be made to take some of these consultations and these abilities to appeal out of the local level, because local committees and councillors are always going to be incentivized to listen to their angriest existing residents. And then that comes at the expense of younger new residents who will never get to move in or have a home of their own in those neighbourhoods.

So, Mike, if the trilemma is breaking housing in much of Canada, how do we actually fix this?

Mike Moffatt: Well, I think there are a couple of things.

So I think we need particularly higher orders of government, the province and the federal government, to be realistic about how much densification is actually going to happen. We keep overestimating it, in part, because we're not addressing all of these other structural barriers.

So I think they need to have realistic estimates of densification, and then go, okay, if we're only going to get this much densification, either we need to let cities build out more, or we need to tamp down on population growth, right? But you can't have it all ways.

I think the second thing that we need to do, particularly at the provincial level, though the federal government can do this [too], is to set minimum standards for cities. I think some of these decisions have to be taken out of the hands of municipalities, and set minimum standards where the province says, ‘No, you can't have a two-story height limit, that is unreasonable. We're going to make it a three-story minimum across the province.’ That doesn't mean that every house is going to be three stories, certainly not. Just saying that you could build that if you want to.

I think at the local level, it just gives too much control to the voices that veto, where if it's done at a higher order of government, and the rules are set equitably across the province, then I think that's a bit easier to do.

I'm not optimistic that our provincial government will do this. Maybe the federal government could require it as part of a revised housing accelerator. But I think that's it. I think it's getting some real reforms to densification, but also some realism about how much densification we're actually going to get, and then adjusting our other policies accordingly.

Sabrina Maddeaux: Absolutely. Well, thank you, everyone, for watching and for listening and to our fantastic producer, Meredith Martin.

Mike Moffatt: And if you have any thoughts or questions about trilemmas or triangles, please send us an email to the [email protected]

Sabrina Maddeaux: We'll see you next time.

Additional Reading that Helped Inform the Episode:

How Community Consultation is Ruining Democracy

This podcast is funded by the Neptis Foundation

Brought to you by the Missing Middle Initiative https://www.missingmiddleinitiative.ca/