The Next Housing Minister Must Restore the Dream of Homeownership

Young Canadians have given up hope

Highlights

Given how home prices have become disconnected from incomes, many Millennials and Gen Z report that homeownership has become “unattainable,” with many having given up on ever owning a home.

Supply plays a large role. Last year, in Canada, there were 67,000 freehold (non-condo) ownership housing starts; 20 years ago, there were over 124,000.

Condo starts, which had been strong, are starting to evaporate due to the worst pre-construction sales market in Canada's largest cities in the last 30 years.

This understates the lack of supply growth in ownership housing, as many existing homes have shifted from ownership to the rental market to house record numbers of newcomers from abroad.

The next Housing Minister will face the colossal challenge of restoring the dream of homeownership through increasing freehold ownership starts, resurrecting the condo market, and building on the substantial growth in rental starts that has occurred over the last decade.

Leading a wartime-like effort

Expectations were set stratospherically high when the press release containing the Liberal housing plan was titled “Mark Carney’s Liberals unveil Canada’s most ambitious housing plan since the Second World War.” Tomorrow, the government will name its new Housing Minister, who will need to achieve results that meet the ambition of that title. No pressure.

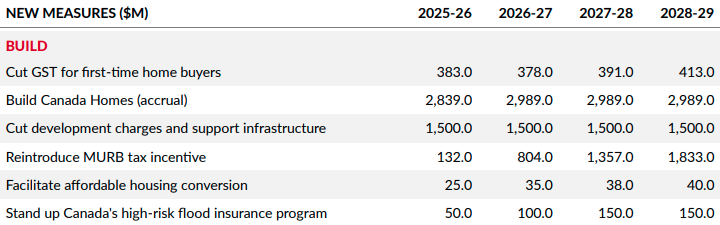

The Housing Minister will have to implement the Liberals' housing campaign promises, as shown in Figure 1. These promises include boosting the supply of social housing and implementing a suite of measures, including better data, lower taxes, and faster approvals, that benefit the entire housing spectrum.

Figure 1: Liberal housing campaign promises and costing

Source: Liberal Party platform.

These measures alone do not constitute a wartime-like effort, and they will not be enough. The federal government must also ensure that all parts of the housing market operate as effectively and efficiently as possible, which will require additional targeted policies. While the Liberals are putting real dollars behind rental-focused policies (MURB, Build Canada Homes), their only ownership-focused program, a GST cut, is relatively modest.

Housing policy has an important role to help those most in need, but it should not ignore the needs of the middle class. At the Missing Middle Initiative, we have set the following North Star, which we believe should guide policies aimed at middle-class prosperity:

Missing Middle Initiative’s North Star: A Canada where every middle-class individual or family, in every city, has a high-quality of life and access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options that are affordable, adequate, suitable, resilient, and climate-friendly.

As the North Star makes clear, individuals and families have different needs and should have the choice to buy or rent. This is not about the government favouring buying over renting (or vice versa); it is about governments ensuring both remain options while recognizing that the policy instruments required to address issues in the rental market may be different than those required to address issues in the ownership market.

Both the ownership and rental markets face challenges. Poll after poll shows the fragility of the homeownership dream for young Canadians. Even relatively optimistic ones, like this late-October 2024 poll from Scotiabank, show that Millennials and Gen Z have not completely given up hope; they do believe that homes are currently “unattainable” for them. Given the disconnect between prices and incomes, particularly in markets like Southern Ontario, young adults are being generous when they describe housing as merely “unattainable.”

Federal reforms must boost the supply of both rental and ownership housing to restore affordability in each market, while recognizing that ownership housing is, in reality, two markets in one: the condo market and freehold (non-condo) owner-occupied homes.

Yes to reform, no to bailouts

The next Housing Minister must clearly define what they are trying to accomplish and distinguish between metrics and goals. Rightly or wrongly, the federal government has set a housing start target for 500,000 units a year. However, the goal should not be to build 500,000 homes for the sake of 500,000 homes.

We would suggest that the ultimate goal for middle-class housing should be as follows:

The housing goal of the federal government is to create well-functioning ownership and rental housing systems and markets, that can respond as quickly as possible to changes in demand, to ensure the government’s commitment to housing as a human right for all is realized. For the middle-class, that vision requires every individual or family, in every city, has a high-quality of life and access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options that are affordable, adequate, suitable, resilient, and climate-friendly.

The focus on well-functioning markets is crucial. The objective should not be to bail out underperforming companies in the housing space or to subsidize the middle class; those subsidies are best targeted at those most in need. Rather, it is to fix broken or out-of-date regulatory systems and taxes and address market failures that prevent the construction of an adequate supply of housing.

Figure 2: The proper objectives of federal middle-class housing policies

Of course, the dividing line between a subsidy and a market-correcting measure is often fuzzy, but the focus should be on creating sustainable, well-functioning markets, not artificially boosting supply or demand (or both). This brings us to our first market: freehold ownership housing.

Non-condo ownership housing construction is at its lowest levels in decades. Where’s the plan to address this?

The CMHC’s Housing Market Information Portal shows that in each of 2023 and 2024, housing starts for non-condo ownership housing were under 70,000 units per year. The only other time since 1990 that starts fell that low was in 1995. In other words, the last two years were among the three worst years for non-condo ownership housing starts in the last 35 years.

Figure 3: Non-condo ownership housing starts, number of units, by year, in Canada

Data Source: Housing Market Information Portal

The number of housing starts does not capture the supply-demand imbalances created in the non-condo ownership market. Comparing population growth makes it crystal clear why non-ownership condo housing is all but unattainable to the middle class in much of Canada.

Figure 4: Non-condo ownership housing starts, number of units, and population growth, number of persons, by year, in Canada

Data Source: Housing Market Information Portal, Quarterly Demographic Estimates.

Even this comparison does not fully capture the challenges for the middle-class in obtaining a non-condo-ownership home, as it does not include the loss of ownership inventory due to previously owner-occupied homes being converted into rental housing to accommodate growing numbers of international students and other disproportionately renter groups.

The situation does not appear much more promising when we add condos to the mix. Last year, 132,000 ownership homes, both condos and non-condos, were started in Canada. This was the second-lowest year since 2001 and was nowhere near enough to keep up with population growth.

Figure 5: Ownership housing starts, both condos and non-condos, number of units, and population growth, number of persons, by year, in Canada

Data Sources: Housing Market Information Portal, Quarterly Demographic Estimates.

Despite rapid population growth and some of the lowest non-condo ownership housing starts in recent memory, restoring the dream of ownership does not appear as a priority on the Liberal platform. While there are measures to help the housing system across the board, even their plan to reduce development charges is aimed at purpose-built rentals and condos rather than freehold ownership housing.

The only piece that speaks to restoring the dream of homeownership is their planned GST rebate to first-time homebuyers, which is so watered down that it will not incentivize the construction of very many new homes. The Liberals have estimated the rebate will cost roughly $400 million per year. Divided over 132,000 ownership homes (both condos and non-condos), this lowers the average after-tax cost of an ownership home by $3,000. That’s not nothing, but also not enough to facilitate the kind of increase in housing starts compatible with a wartime-like effort.

The federal government must do more to fix a broken housing ownership market. The obvious first step is to reduce the restrictions on their GST rebate, in order to reduce one of the largest taxes on ownership housing construction. That will not be enough, by itself, but it is a start. Further policy reforms will be needed to reform regulatory barriers and fix market failures, but none of that will happen until the federal government acknowledges the challenges in the ownership market.

Which brings us to the condo market.

Governments need to ask, “Where should pre-construction condo funding come from?”

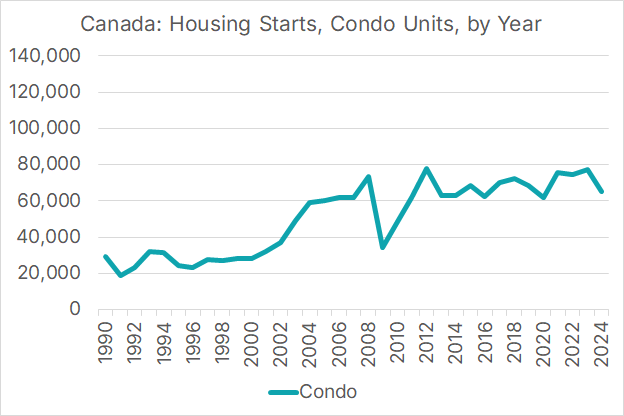

Since the end of the financial crisis, condo starts have consistently been between 60,000 and 80,000 units per year. This is almost certainly coming to an end in 2025, as starts fell substantially last year and look to continue on their downward trend.

Figure 6: Condo ownership housing starts, number of units, by year, in Canada

Data Source: Housing Market Information Portal

Starts are down 43% in the first quarter of 2025 relative to Q1 2024. Pre-construction condo sales have all but evaporated in the Greater Vancouver Area. In the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, they are down 80% from their 10-year average and at their lowest levels since the mid-1990s. This year’s pre-construction sale is next year’s start, so the starts data for 2026 and 2027 should look particularly ugly. The federal government is going to have a tough time doubling housing starts with a condo market in free-fall.

It is unclear if the federal government is aware of this problem; the word “condo” appears nowhere in its platform. If they are aware of it, their temptation will be to design policies which are temporary bail-outs, an understandable reaction when companies like Rennie are laying off employees.

Instead, the next Housing Minister should ask themselves two questions:

QUESTION 1: How should the construction of condos be financed?

Condos are traditionally financed through pre-construction sales, where the buyer makes a down payment on the unit. Because owner-occupants typically aren’t in a position to make a down payment and then wait years before they get their new home, in many markets, investors make up the majority of pre-construction sales, many of whom will sell that unit upon completion. The Liberal government has never been particularly comfortable with the role of investors in the housing market, and the whole model of investors financing condos through pre-construction sales only works if condos are appreciating much faster than the rate of inflation, which runs counter to affordability.

In short, if the federal government wants the condo market to continue to exist and if it wants to lessen the role of speculative investors in housing, it must create alternative mechanisms to fund condo construction.

QUESTION 2: How can governments address the condo cost-of-delivery crisis?

Condos will only be built if their construction cost is at least 12-15 percent lower than the market price. If the federal government wants market prices to fall (or at least not rise), then it needs to find ways to lower costs. Brad Jones, of Wesgroup, illustrated the costs to build a $1.5 million condo in Vancouver:

$294,000 (20 per cent) is for land acquisition

$490,000 (32 per cent) is for hard costs (i.e. labour, building materials)

$102,000 (7 per cent) is for soft costs (i.e. architectural designs, legal fees)

$92,000 (6 per cent) is for marketing and realtor commissions

$77,000 (5 per cent) is for finance charges and loan interest

$267,000 (18 per cent) is for government taxes and fees

$178,000 (12 per cent) is the gross profit margin required by banks to provide financing

Governments must find ways to reform regulations and taxes and address market failures that keep these costs higher than they otherwise would be to address what Jones calls the cost-of-delivery crisis.

While the condo market is cause for extreme pessimism, rental construction illustrates the power of well-designed policies.

Finally, governments must keep up the good work when it comes to rental construction

While the condo market is cause for extreme pessimism, rental construction illustrates the power of well-designed policies. Canada went several decades without building much rental housing. But thanks to a suite of policies from CMHC financing programs to removing the GST on purpose-built rental construction to the introduction of accelerated-capital cost provisions, annual purpose-built rental starts are five times higher today than they were 15 years ago.

Figure 7: Rental ownership housing starts, number of units, by year, in Canada

Data Source: Housing Market Information Portal

However, the remarkable success of these programs largely goes unnoticed, as a massive increase in the number of renters has caused the demand for rental housing to exceed the growth in supply. Over the last decade, the number of non-permanent residents living in Canada has grown by 2.2 million, as compared to 360,000 the decade before.

Figure 8: Increase in the number of non-permanent residents by decade, Canada

Data Source: Quarterly Demographic Estimates.

As an aside, it is truly remarkable the lengths some analysts will go to to give non-population growth explanations for why investors were buying up single-family homes and renting them out. Canada is a country that went decades without building much rental housing, then, unannounced, brought in over 2 million renters through a series of non-permanent resident programs. How could that not create incentives to convert ownership housing to rental housing?

Unlike the two ownership markets, the role of the next Housing Minister will be to keep up the good work. Continue enhancing CMHC financing programs, work with the Finance Minister to implement MURB, and address the cost-of-delivery crisis.

We’re wishing you the best of luck (you’re going to need it)

Implementing the “most ambitious housing plan since the Second World War” is not going to be an easy task, particularly when that plan contains a number of holes, including policies to address the ownership market. If there is any good news, it’s that at current immigration levels, the announced 500,000 homes per year target is overkill; the crisis can be solved at production levels close to 350,000. The bad news is that annual housing starts have never been above 300,000, and just keeping starts at current levels will be a massive challenge given the evaporation of the condo market. But you have a unique position to make a real difference to the future of the country. We’re wishing you the best of luck.