Ten Thoughts on the Liberal Housing Plan

Some things you may have missed

At the Missing Middle, we have received many questions about the new federal Liberal housing plan, particularly from those of you who noticed that some of the planks are recommendations we1 made in the National Housing Accord, Blueprint for More and Better Housing, and the Housing Canada Plan. We hadn’t planned on writing about their (or any other party’s) housing offerings, but the sheer volume of questions makes it worthwhile.

Our goal with this post is not to grade the Liberal housing plan in absolute terms or relative to the plans put forward by other parties. Rather, we’ll give our thoughts on some of the pieces and provide additional context.

This post is an experiment for us. The structure is inspired by NHL commentator Elliotte Friedman’s wonderful 32 Thoughts series. If you enjoy this format, please like this post and subscribe (if you haven’t already). It will encourage us to do more.

Let the experiment begin!

1. The Liberal housing plan extends beyond creating a public builder

There are over a dozen commitments in the Liberal housing plan, which can be broken down into a few categories:

Creation of a new crown corporation called Build Canada Homes (BCH)

Innovation policy to help increase productivity and lower costs in the homebuilding sector.

Tax reforms and a cut to development charges to lower costs and attract investment into homebuilding.

Regulatory reforms

The Liberals clearly want the Build Canada Homes promise to receive the most attention, as it is listed first and in the most detail. It seems to have worked; the bulk of the media attention on the plan has centred around that promise. However, we believe that the tax reform pieces, rather than Build Canada Homes, will have the largest impact on homebuilding.

2. Reintroducing MURB would transform Canadian homebuilding

Halfway down page two on a two-page plan is a promise to reintroduce a tax incentive to facilitate the construction of more rental apartments. The promise:

We will reintroduce a tax incentive which, when originally introduced in the 1970s, spurred tens of thousands of rental housing across the country. Known as the Multiple Unit Rental Building (MURB) cost allowance, this policy helped produce nearly 200,000 units in seven years (1974-81).

A number of groups have been calling for this, and it was recommendation 7b in the Housing Canada Plan.

A MURB program allows individual investors in rental apartments constructed after a certain date to deduct expenses related to that building from their personal taxes. Most notably, it allows investors to flow-through depreciation onto their personal income taxes. This provision is particularly attractive in the current tax environment, as the Liberal government increased depreciation rates on rental apartments from 4% to 10% as part of Budget 2024. That move was designed to encourage investment in apartment construction and was a key recommendation of both the National Housing Accord and Blueprint for More and Better Housing. The synergistic effect of MURB, a 10% depreciation rate, and 2023’s elimination of GST/HST on purpose-built rental construction on creating a favourable tax environment for apartment construction cannot be overstated.

The re-introduction of MURB will not only accelerate the construction of apartment buildings, particularly smaller ones, but it will also shift the investment decisions of smaller-scale real estate investors. Over the past couple of decades, if a mom-and-pop investor wanted to get into rental housing, they would often buy a condo (either pre-construction or existing) and rent it out. Others, noticing the international student boom, would buy up single-family homes that were either proximate to campus or along a bus route and rent them out to students. This has caused families to have to compete with investors for housing. But with MURB, there are significant tax advantages to building, rather than buying, which will shift investment decisions.

MMI has differed from progressive Canadian orthodoxy on the policy solutions to the “investors vs. families” question, where the progressive orthodox position has been a ban on investor purchases of homes. Our position has been that families getting outbid by investors is absolutely a problem worthy of public policy attention, but it is also a natural market reaction to government policies that brought millions of additional renters into Canada via increased immigration targets and skyrocketing growth in the number of non-permanent residents. Any well-meaning attempts to block that market reaction, to tip the scales towards buyers and away from renters, would put already marginalized renters in an even more precarious position. Workable solutions to “investors vs. families” look to root causes of the conversion of ownership housing into rental stock, not simply outcomes, and should involve some combination of immigration reform and policies to accelerate rental construction.

Reintroducing MURB would be a highly beneficial reform which would shift investor activity away from purchasing existing family homes and towards constructing new rental housing. That is not to suggest there won’t be negative unintended consequences; we are likely to see investors buy up smaller homes in lower-income neighbourhoods, knock them down, and put up apartments, which risks displacing existing residents. Displacement will need to be closely monitored, and additional policies may need to be enacted to protect those residents.

MURB will lead to the construction of more purpose-built rentals by diverting capital from acquiring existing buildings to constructing new ones. That is a good thing. We are cautiously optimistic that we are starting to see Canadian progressivism that aims to build rather than ban.

3. 500,000 homes a year is too many

The promise:

The Liberal housing plan will double Canada’s current rate of residential construction over the next decade to reach 500,000 homes per year…

This has been interpreted in some circles to mean that the Liberals are proposing that their new public builder would build 250,000 homes per year. Instead, what they are suggesting is that their combined existing and proposed reforms will cause total homebuilding to grow from 250,000 to half a million units a year.

Simply put, Canada will not reach 500,000 homes per year with these reforms. There are too many unaddressed barriers and bottlenecks preventing that. However, we would also argue that such a target is undesirable. We estimate that over the next six years, we need around 330,000 homes per year to keep up with population growth and address the current shortage. Building 500,000 a year at current population growth levels is simply unsustainable and would create a boom-bust cycle for homebuilding.

To be clear, we don’t think there is a meaningful risk that this plan, if implemented, would cause an oversupply of housing. Rather, the 500,000 home target will not, and should not, be achieved.

4. A public builder is a blast from the past

The promise:

A Mark Carney-led Liberal government will create a new entity called “Build Canada Homes” (BCH), which will get the federal government back in the business of building homes. BCH will have three key functions: building affordable housing at scale (including on public land), catalyzing a new housing industry, and providing financing to affordable homebuilders.

Like the MURB program, this is a blast from the past. The federal Liberals are proposing a new crown agency that will carry out many of the same functions that the CMHC did in the 1940s and 1950s, when there were massive post-war housing shortages.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the federal government facilitated the development of large numbers of strawberry box homes based on a catalogue of pre-approved designs. The federal government has already committed to reintroducing the catalogue (recommendation 7b of the National Housing Accord), so creating the BCH is the logical next step.

However, a BCH should not try to develop2 the same types of homes it did in the 1940s and 1950s. The conditions that were in place then, most notably large parcels of inexpensive land in Southern Ontario, are not in place now. Instead, the focus should be on missing middle type housing, such as fourplexes and small apartments. This will prove challenging, as these homes take longer to build than single-detached units, municipal permitting problems are lengthy and unwieldy, and the Building Code makes the housing typologies “ill-fitting” for many families. These are all the reasons why the private sector is hesitant to build these homes. Unless governments deal with those issues, BCH is going to run into the same roadblocks as the private sector when it comes to missing middle housing and achieve similar outcomes.

Finally, we have heard concerns from the development community that CMHC’s multi-unit mortgage loan insurance program (MLI Select) and the Apartment Construction Loan Program (ACLP) would be moved out of the CMHC and to this new agency, causing substantial delays. I believe such a move would be a mistake, and I hope the federal government does not attempt such a move.

Edited to add: After this piece was published, we heard from a contact in the Liberal war room who texted us the following: “CMHC will absolutely retain MLI Select and ACLP.”

5. Limiting the GST rebate to first-time homebuyers is a missed opportunity

The promise:

These measures will build on the elimination of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) for first-time homebuyers on homes at or under $1 million. This tax cut will save Canadians up to $50,000.

Mike has written a couple of pieces on the GST new housing rebate for The Hub: one in early October 2024 promoting the idea and a second in late October 2024 giving a mostly positive analysis of the Conservative GST plan on housing.

Because the GST only applies to new housing, it acts as a development tax (or, if you prefer, a development charge), increasing the cost of homebuilding and causing fewer homes to be built. While both the Liberal and Conservative moves are being framed as reducing the price of homes by 5%, the supply-side effects are vitally important.

The Liberals have limited their plan to first-time homebuyers. In our view, this is a mistake. The goal should be to increase the supply of housing, and such a restriction limits the effectiveness of the program. For example, the existence of the GST on housing discourages seniors from downsizing from their larger suburban homes to smaller, newly constructed senior-friendly housing. By eliminating the GST on housing, we can get more of these senior-friendly homes built and free up larger suburban homes for the next generation of families.

The Conservative plan does not suffer from this flaw; however, it is financed by eliminating beneficial (if flawed) programs like the Housing Accelerator Fund.

6. The Liberal plan leans heavily on innovation policy

The promise:

BCH will also catalyze the housing industry and create higher-paying jobs by providing $25 billion in debt financing and $1 billion in equity financing to innovative Canadian prefabricated home builders. Prefabricated and modular housing can reduce construction times by up to 50 per cent, costs by up to 20 per cent, and emissions by up to 22 per cent compared to traditional construction methods.

The Liberal housing platform heavily emphasizes Innovation and adopts many of the philosophies of RealInnovator’s 2024 Innovation Agenda for Canadian Real Estate3. The Liberal promise adopts elements of the Blueprint for More and Better Housing’s recommendations VII.1 on innovation funding and VII.2 on low-cost, low-carbon technologies.

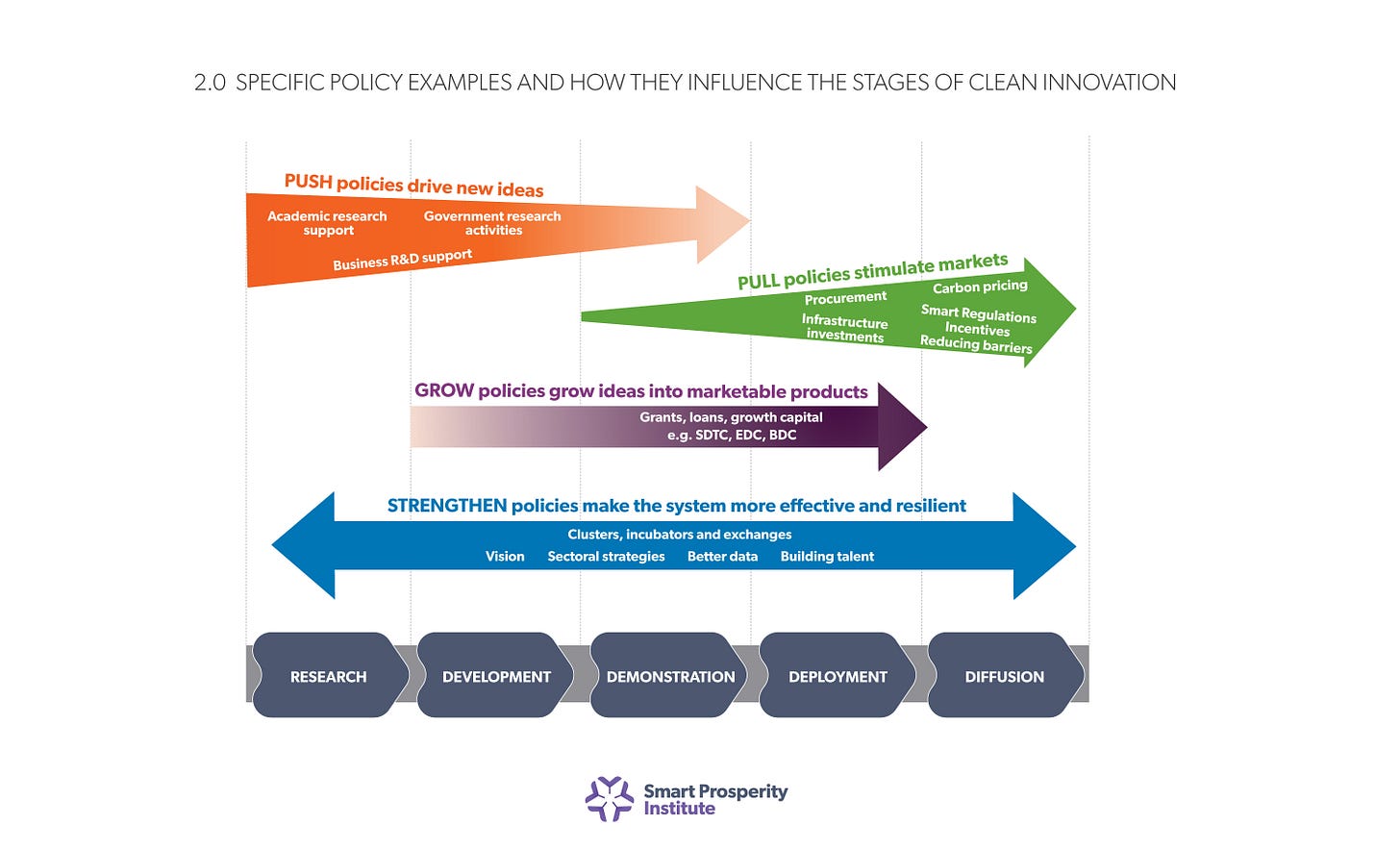

The policy tools needed to stimulate innovation in new housing technologies are not fundamentally different than those needed in clean energy or electric vehicle manufacturing. The Smart Prosperity Institute has written extensively about innovation policy tools; I highly recommend their How Clean Innovation Happens primer. When it comes to housing innovation, the federal Liberal plan incorporates GROW policies (growth capital) and PULL policies (procurement).

Innovation is challenging, so we should not expect this program to yield immediate benefits, but it has the potential for substantial long-run benefits.

We were particularly pleased to see this promise in the Liberal plan:

BCH will issue bulk orders of units from manufacturers to create sustained demand. Financing will leverage Canadian technologies and resources like mass timber and softwood lumber.

As it is very similar to recommendation VII.4 in the Blueprint:

Develop a procurement strategy for the innovative homes in the CMHC pre-approved catalogue, including guaranteed minimum orders. A countercyclical commitment to increase orders during downtimes in the wider market is needed for innovative companies to survive recessions and achieve scale.

Finally, we highly recommend About Here’s new video on the challenges and opportunities in factory-built approaches to homebuilding. It is a fantastic primer on the subject.

7. Lowering development charges is a worthwhile goal, but the Liberals need to go back to the drawing board

The promise:

We will cut municipal development charges in half for multi-unit residential housing and work with provinces and territories to make up the lost revenue for municipalities for a period of five years. For a two-bedroom apartment in Toronto, the cost savings from this measure would be approximately $40,000.

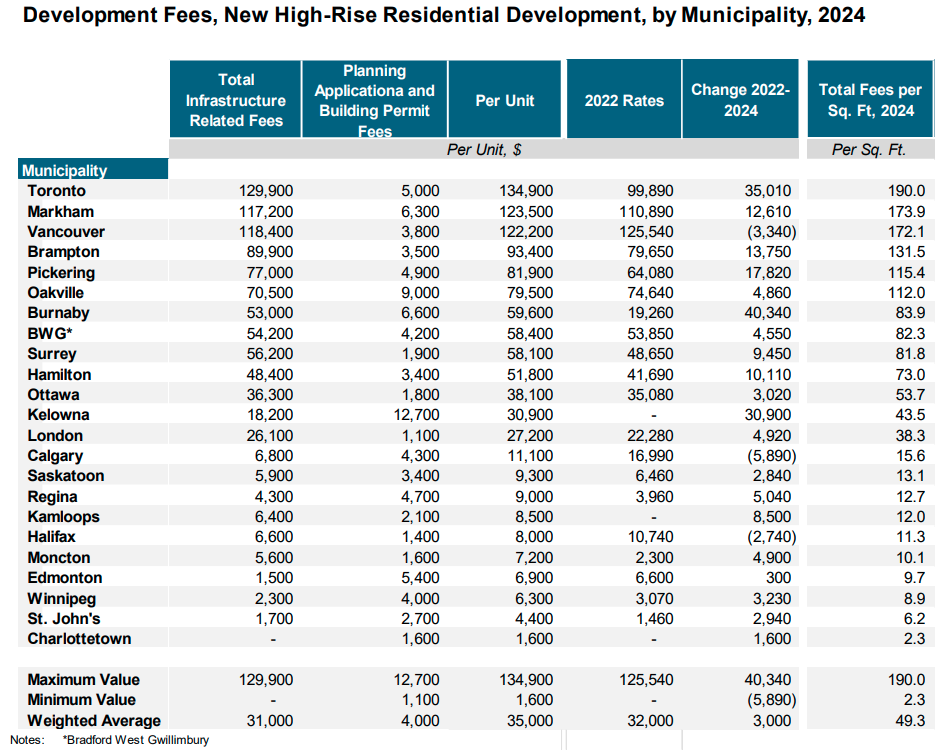

We have an entire series on the problems with high development charges, so you may be surprised to learn that we’re not fans of this promise to cut development charges, at least as it is presently constructed. First, the federal government lacks the institutional knowledge on the rates and types of charges assessed at the municipal level across the country. Secondly, as shown by a recent CHBA study prepared by Altus Group, development fees for multi-unit residential vary widely across the country.

A federal government commitment to finance the half-cut would provide substantial funding to Toronto, Markham, and Vancouver and almost nothing to Edmonton, Winnipeg, and St. John’s. This would be deeply unfair, as it penalizes cities for keeping charges at a reasonable level, and frankly, would not be great for national unity.

There are potential corrective fixes to this problem. The federal government could instead require municipalities to freeze these fees and offer flat-sum development charge rebates of, say, $10,000 a unit. If municipal fees do not exceed these fees, the municipality would be able to keep the remainder. So, in Toronto, the city would have to extend the full rebate to the developer, but in Moncton, $5,600 would go to the developer, and the city would be allowed to retain the remaining $4,400.

That said, we believe the more direct route is for the government to cut the development charge that is fully under its control (the GST) rather than devising complex mechanisms to cut the development charges of other orders of government.

What is ultimately needed isn’t simply for development charges to go down, but rather wholesale reform to find fairer and less expensive ways to fund infrastructure. Provinces will need to take the lead on this, but the federal government can play an important but secondary role.

8. Tracking municipal progress is long overdue

The promise:

We will publicly report on municipalities’ progress to speed up permitting and approval timelines and implement other commitments under the Housing Accelerator Fund;

All we can say is: ABOUT TIME. We have been highly critical of the lack of accountability in the HAF program. Mike has a short LinkedIn post describing the issue. We are glad to see the Liberals are committing to fixing it.

9. Can anyone tell us what the Liberals are proposing with the Building Code?

The promise:

We will accelerate reform and simplify the Building Code to speed up approvals and streamline regulations.

Sounds great, but we have no idea what this means in practice. What are the Liberals proposing here? Legalizing small, single-egress apartments? Something else? Without more details, this is a meaningless promise. However, this isn’t to suggest reforms aren’t badly needed. This footnote in a Possible Somewhere post is a good place to start:

To summarize this laundry list at a very high level- single stair fire code, an elevator code harmonized with europe’s, zoning that allows small apartments on residential streets, condo and tarion laws that support condominimizing, more liberal height limits, repeal of setbacks that make terrible windows and an inability to add a courtyard, parkland dedications, excessive electrical capacity minimums and regressive develompent charges for starters!

10. Tweaking the tax code can help accelerate new construction

The promise:

We will facilitate the conversion of existing structures into affordable housing units by reducing the tax liability for private owners of multi-purpose rental when they sell their building to a non-profit operator, land trust, or non-profit acquisition fund - so long as the proceeds are reinvested in building new purpose-built rental housing.

This proposal is strongly aligned with recommendations we have made in a number of pieces, including Recommendation VI.3.iv of the Blueprint for More and Better Housing:

VI.3.iv: Providing a capital gains tax break to private owners of multi-purpose rental when they sell their building to a non-profit operator, land trust, or non-profit acquisition fund, so long as they reinvest the proceeds in building new purpose-built rental housing.

Recommendations 3b, 3e, and 8 in the National Housing Accord:

3b: Defer capital gains tax and recaptured depreciation due upon the sale of an existing purpose-built rental housing project, providing that the proceeds are reinvested in the development of new purpose-built rental housing.

3e: When selling to a non-profit operator, land trust, or non-profit acquisition fund, provide a capital gains tax break to private owners of multi-purpose rental. This initiative would incentivize selling to non-profits and protect affordable purpose-built rental housing.

8: Create property acquisition programs for non-profit housing providers to help purchase existing rental housing projects and hotels and facilitate office-to-residential conversions.

We particularly like this idea, as it accomplishes two things at once. First, it helps keep existing housing units affordable, and second, it encourages the construction of new purpose-built rental apartments. Add this into the mix with MURB, along with previous changes to eliminate GST on purpose-built rental construction and increases in the capital cost allowance depreciation rate, and you have a federal tax system that is highly supportive of building new rental housing.

Final thoughts

This post only scratched the surface; there is much more we could talk about. If you enjoyed this piece, please give the piece a like and subscribe if you haven’t already. This would encourage us to write up a follow-up piece or do a similar analysis of the housing promises of the other parties.

All three of these documents are the result of a coalition of actors in the housing space coming together and crafting a set of solutions to the housing crisis. MMI’s Founding Director, Mike Moffatt, held the pen on all three documents, but they were very much a group effort. And, with any group project, members did not necessarily agree with every single component or recommendation (including Mike), but were comfortable enough with the package as a whole to sign off.

Although the Liberals are branding this as “building” homes, more accurately, this program would be “developing” homes, as the federal government would almost certainly be contracting construction out to private homebuilders.

The Innovation Agenda was ghost-written by MMI’s Founding Director, Mike Moffatt.