From Boom to Bust in Population Growth

What it means for housing affordability

Highlights

Over the past two decades, Ontario and British Columbia have experienced significant deterioration in middle-class housing affordability for several reasons, the primary being a combination of housing shortages and the global secular decline in real interest rates, which acted as an accelerant.

The supply-demand imbalance at the heart of the shortage was the result of governments enacting slow-growth housing policies alongside fast-growth population growth policies.

In 2024, the federal government enacted sweeping reforms to lower population growth, and now British Columbia and Ontario, along with almost all of the rest of Canada, are experiencing nearly no net population growth.

Not surprisingly, rents are falling in both provinces.

Alberta is the outlier, which is experiencing lower rents and robust population growth. This population growth, however, is being matched with substantial growth in the housing stock.

The experience in British Columbia, Ontario, and Alberta shows that both supply and demand matter when it comes to housing affordability.

Putting the pedal to the metal, then slamming the brakes

Ontario and British Columbia are experiencing record-low levels of population growth, and this is having a substantial impact on the housing market.

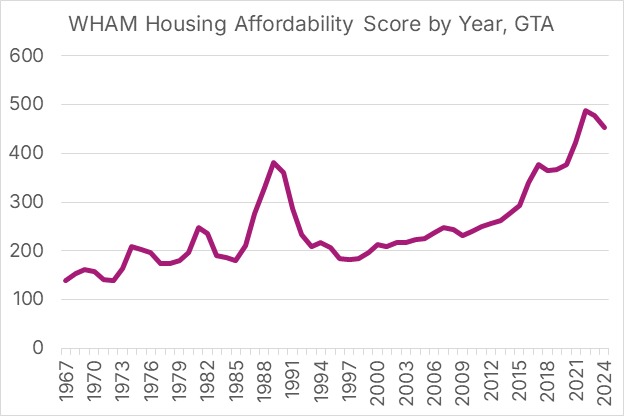

Middle-class housing affordability, particularly in Southern Ontario and Lower Mainland British Columbia, has deteriorated over much of this century, with big spikes in unaffordability in 2016 and 2021, as outlined in the piece Southern Ontario’s Home Affordability Crisis Remains at Near-Record Levels.

Figure 1. GTA - WHAM Total housing affordability score for the GTA since 1967. Higher = Less Affordable

Source: Southern Ontario’s Home Affordability Crisis Remains at Near-Record Levels

There is no single cause of the middle-class housing crisis, but the primary cause is the disconnect between housing policies and population growth policies, which has led to a supply-demand imbalance and a housing shortage. This shortage is compounded by the global secular decline in real interest rates, which acted as an accelerant.

On the supply side, governments increasingly made it more challenging and expensive to build, through a combination of increasingly strict but well-intentioned land use policies (urban growth boundaries, greenbelts), tight zoning rules, lengthy and cumbersome approvals processes, development charges increasing 17% a year during a period of 2% inflation, and an alphabet soup of other rapidly rising housing construction taxes have slowed construction and also caused “housing shrinkflation”, as the majority of new homes have fewer than three bedrooms.

Then there is population growth on the demand side. A combination of increasing immigration targets, the international student boom, and loosening rules on temporary foreign workers led to population growth rates in Ontario and British Columbia more than doubling in 2016, compared to the levels experienced in the previous few years. They would stay at that elevated level until the beginning of the pandemic, drop temporarily, then absolutely explode in 2021-23, due to further increases in immigration targets, and an extreme loosening of temporary foreign worker and international student rules.

The combination of slow-growth housing policies and fast-growth population growth policies inevitably caused too many people chasing too few (and too small) homes, and low real interest rates allowed buyers to place larger bids on increasingly scarce homes, and we were left with markets where the middle-class was entirely priced out.

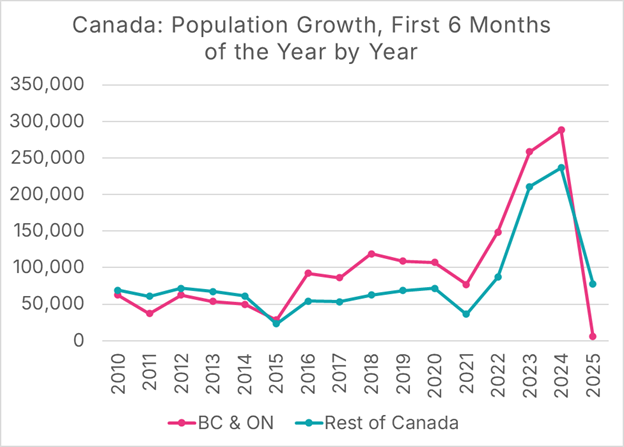

That appears to be changing. Statistics Canada recently released population estimates for the second quarter of 2025. They show that, combined, Ontario and British Columbia experienced almost no net population growth in the first half of 2025.

Figure 2: Population Growth, First 6 Months of the Year, by Year, Canada

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Canada’s Population Estimates. Chart Source: MMI

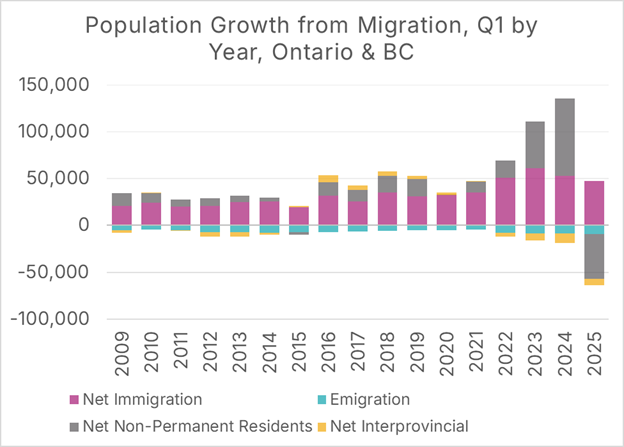

This drop was not accidental. In 2024, the federal government lowered immigration targets and released a plan to decrease the number of non-permanent residents living in Canada from three million to two million. Their plan appears to be working. Ontario and British Columbia went from having large net inflows of non-permanent residents to large net outflows. The two provinces have also experienced small decreases in permanent residency immigration, along with small increases in emigration and the number of persons moving to other provinces.

Figure 3: Population Growth from Migration, Q1 by Year, Ontario and British Columbia

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Canada’s Population Estimates. Chart Source: MMI

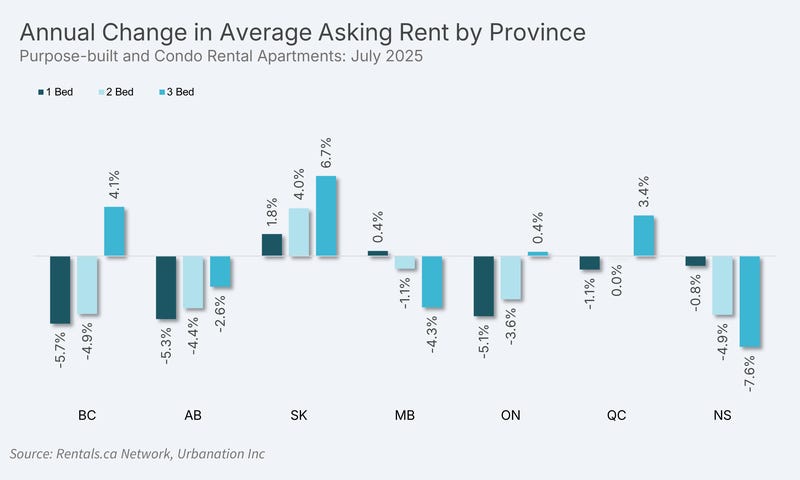

All else being equal, substantially lower population growth should lead to a slowing of rent growth, or even declining rents. Theory and practice align in this case, as rents have substantially fallen in both British Columbia and Ontario, for one- and two-bedroom apartments.

Figure 4: Annual Change in Average Asking Rent by Province, July 2025

Chart Source: Rentals.ca

Alberta and Nova Scotia have experienced the largest rental rate declines, so we would expect that these provinces would also be experiencing large drops in population growth. While that theory holds for Nova Scotia, Alberta is still experiencing rapid population growth. In fact, it is the only province in Canada that is experiencing any significant growth in 2025.

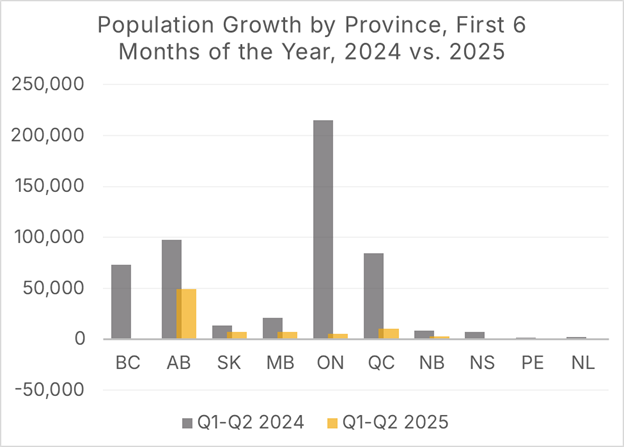

Figure 5: Population Growth by Province, Number of Persons, First 6 Months of the Year, 2024 vs. 2025

Data Source: Statistics Canada, Canada’s Population Estimates. Chart Source: MMI

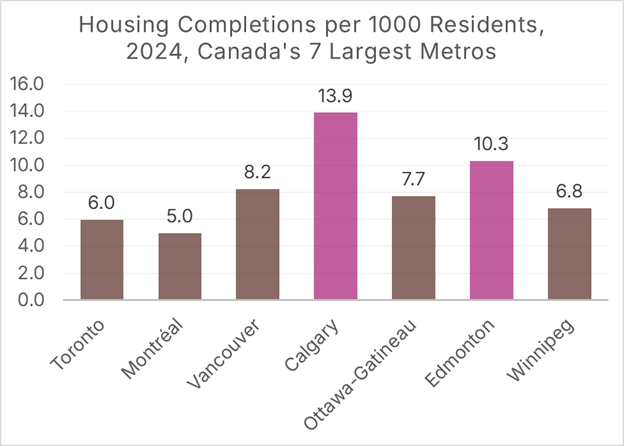

However, our claim is not that population growth, by itself, causes a lack of affordability. Rather, it is the disconnect between population growth and housing growth. While Alberta continues to experience high population growth, cities in the province are also growing their housing stock at a much faster rate than the rest of the country.

Figure 6: Housing Completions per 1000 Residents, 2024, Canada’s 7 Largest Metros

Data Sources: CMHC Housing Market Information Portal, Statistics Canada, Canada’s Population Estimates. Chart Source: MMI.

Both supply and demand matter. As long as our population growth policies and our housing policies (along with our education, health care, infrastructure, etc. policies) are aligned, Canada can handle growth. However, Ontario and British Columbia illustrate what happens when governments attempt to combine slow-growth housing policies with a fast-growth population ideology.