Housing Needs Change as People Age: RoCA 2.0

“A unit is a unit is a unit” thinking misses the importance of family-sized homes.

Highlights

When governments set housing targets, those targets are in terms of “units”.

However, housing needs differ based on a person’s age and the size of their family. This distinction is lost, however, in simple unit targets, where a small studio apartment is treated as functionally equivalent to a 3-bedroom family-sized home.

One reason that governments adopt simple unit targets is that methodologies to estimate housing shortages, such as the RoCA Benchmark, make no distinction between unit types.

To fix this problem, we created a RoCA Benchmark 2.0, which differentiates between ground-oriented housing and apartments and between ownership and rentals.

Using this new methodology, we show that as of Census 2021, Ontario had substantial shortages of rental apartments, ground-oriented ownership housing, and, surprisingly, condo apartments.

These housing needs, however, will change as Ontario’s population ages.

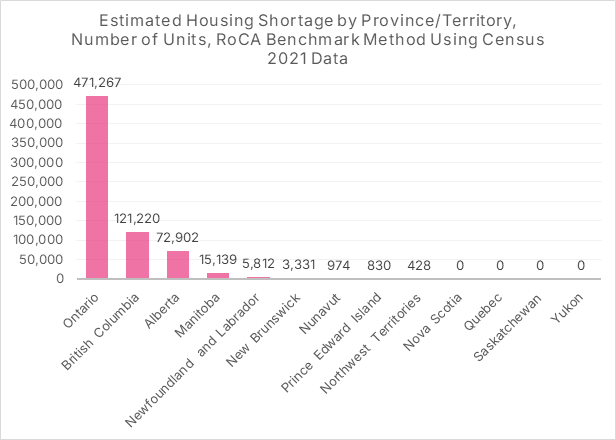

In past CHMP pieces, we have posted the following chart showing the extent of housing shortages in each province as of Census 2021. The calculation, which utilizes the RoCA Benchmark, finds that, as of May 2021, Canada had a housing shortage of 690,000 units, with 470,000 of those occurring in Ontario.

Figure 1. Canadian Housing Shortages by Province as of 2021

The RoCA Benchmark, while a powerful tool, suffers from the limitation that it treats all homes as identical. To review, the RoCA Benchmark estimates how many homes a place should have using the following parameters:

Figure 2. RoCA Benchmark v1.0 Parameters

A shortage is defined as the number of homes a place should have minus the number of homes it actually has. But that treats all homes as functionally identical. But we know that a small studio condo cannot house as many people as a 4-bedroom family-size home. Furthermore, we also know that people’s housing needs change as they get older.

In short, we need to move away from the “a unit is a unit is a unit” thinking.

Fortunately, the “a unit is a unit is a unit” limitation of the RoCA Benchmark is a fixable problem. We can create a more granular RoCA 2.0.

Creating a RoCA Benchmark 2.0

The existing RoCA Benchmark is used for two related purposes:

Estimating housing shortages at the end of each Census period by converting Census population data into RoCA Benchmark Households and comparing that to Census dwelling counts.

Estimating the change in housing shortages between Census periods by converting Statistics Canada population growth data into RoCA Benchmark Household Growths and comparing that to CMHC data on housing starts or housing completions.1

Our goal is to create a more granular RoCA Benchmark that breaks housing down into types. But to do so, we must stay within the constraints of Census, Statistics Canada, and CMHC data.

Also, in an ideal world, our revised RoCA Benchmark would differentiate homes by the number of bedrooms for the simple reason that a 3- or 4-bedroom dwelling can house more people than a small apartment. Unfortunately, this is not an option as CMHC housing starts and completions data are not broken down by bedroom. This gap creates a limitation.

The CMHC starts data, however, does break housing types down into four-types: Single-detached, semi-detached, row (townhouses), and apartments. They define each as follows:

A “single-detached” dwelling is a building containing only one dwelling unit, which is completely separated on all sides from any other dwelling or structure.

A “semi-detached” dwelling is one of two dwellings located side-by-side in a building, adjoining no other structure and separated by a common or party wall extending from ground to roof.

A “row” dwelling is a ground-oriented dwelling attached to two or more similar units so that the resulting row structure contains three or more units.

An “apartment and other” dwelling includes all dwellings other than those described above, including structures commonly referred to as duplexes, triplexes, double duplexes and row duplexes.

Note here that the CMHC’s definition of “apartment” covers a lot of housing types that laypeople may not think of as apartments, such as a stacked triplex.

Although CMHC housing starts data does not provide bedroom breakdowns, Census data does. A Census 2021 housing data table shows that there are substantial differences in the average number of bedrooms each of these housing types has. In particular, the first three categories have a much higher proportion of 3-bedroom units suitable for families with children.

Figure 3. Number of Homes by Type and Number of Bedrooms, Canada, Census 2021

The differences between ground-oriented housing and apartments become much clearer when we aggregate the data into two categories: one containing single-detached, semi-detached, and row/townhouse units and a second “apartment+” category containing everything else.

Figure 4. Number of Homes by Category and Number of Bedrooms, Canada, Census 2021

Our RoCA 2.0 Benchmark will differentiate between these two categories of housing as a means of moving away from “a unit is a unit is a unit” thinking. Because these two categories have much different proportions of family-sized units, it is an indirect way of incorporating the number of bedrooms into RoCA. We would have preferred to incorporate the number of bedrooms directly, but that is an impossibility until the CMHC starts collecting that data. We hope they do so; when they do, we will create a RoCA 3.0.

The CMHC does, however, break their housing starts and completions data down into “intended market,” though frustratingly, like housing completions, they don’t collect this data for parts of rural Canada, making it impossible to get province-wide or country-wide counts. In the parts of the country they do collect data for, in 2024 there were 95,852 rental units started, 65,013 condo units, 67,101 freehold ownership units, and five co-op units.2

Given the Missing Middle’s goal of ensuring “access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options,” there will be occasions where estimating housing shortages in the rental market separately from the ownership market (and vice-versa). As such, we will incorporate this distinction into RoCA Benchmark 2.0, dividing between rental and ownership (which includes both condo and non-condo ownership units).

The revised RoCA Benchmark 2.0 parameters

Given the Missing Middle’s goal of ensuring “access to both market-rate rental and market-rate ownership housing options,” there will be occasions where estimating housing shortages in the rental market separately from the ownership market (and vice-versa). As such, we will incorporate this distinction into RoCA Benchmark 2.0.

The original RoCA Benchmark parameters were estimated by calculating age-adjusted headship (head-of-household) rates from Census 2016, with the year 2016 chosen as the baseline as it was before Canada’s housing crisis became acute across Canada. The estimates excluded British Columbia and Ontario (the two provinces that had obvious housing shortages even in 2016) to estimate the “Rest of Canada Average” (RoCA).

Using Census 2016 data table 98-400-X2016226, we can estimate revised RoCA parameters, which break units down into categories (ground-oriented and apartments+) and ownership vs. rental.

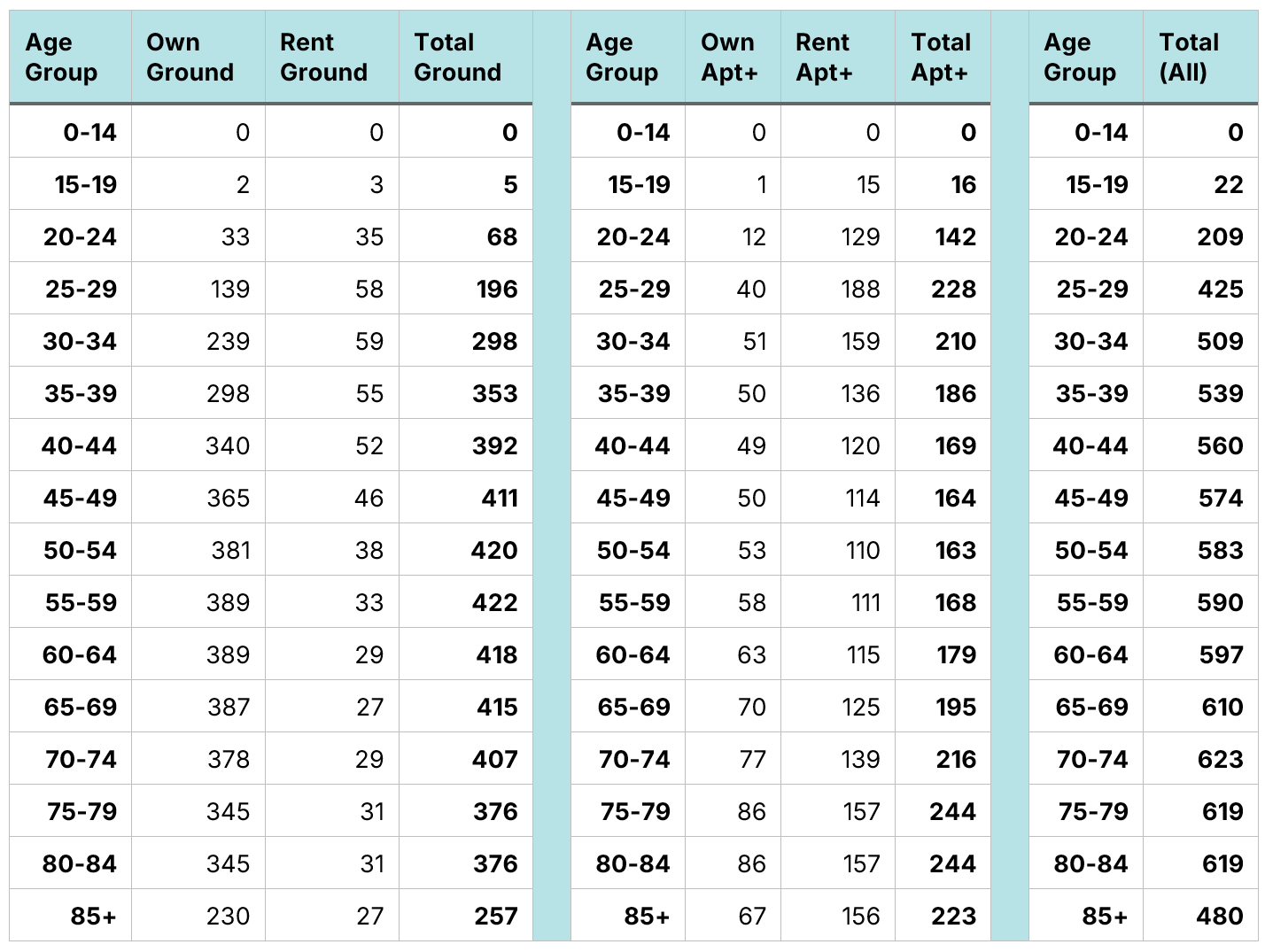

Figure 5. RoCA Benchmark 2.0 Parameters

One positive unintended consequence of using that Census 2016 data table is that it breaks headship rates into 5-year age categories for persons under age 75. The previous RoCA Benchmark utilized 10-year age categories, so that this revision will allow for additional precision. This improvement is particularly important, as the housing needs for 15–19-year-olds (who largely live with a parent) are very different than those of 20–24-year-olds, and the previous RoCA Benchmark lumped them into a single category.

Housing needs evolve as people age

Graphing out the RoCA Benchmark 2.0 parameters provides a dramatic illustration of how housing needs evolve as a person ages.

Figure 6. RoCA Benchmark 2.0 Parameters by Age

Younger adults are far more likely to rent, which includes both apartments and ground-oriented housing. Ground-oriented housing is a particularly common option for students and new graduates; think of all the single-detached homes that are used as student rentals in most University and College towns in Canada.

Ownership of a ground-oriented home is, by far, the most common housing type for persons over the age of 30, as apartment rentals experience a dramatic drop from age group 25-29 to 30-34, and ownership of ground-oriented housing experiences an equally dramatic rise.

These trends change as an individual hits age 65, as both apartment rentals and apartment ownership rise, with ownership of ground-oriented housing experiencing a steady decline after age 64. The decline in ground-oriented housing ownership accelerates quickly as a person enters their mid-80s.

What does this mean for Ontario’s housing shortage?

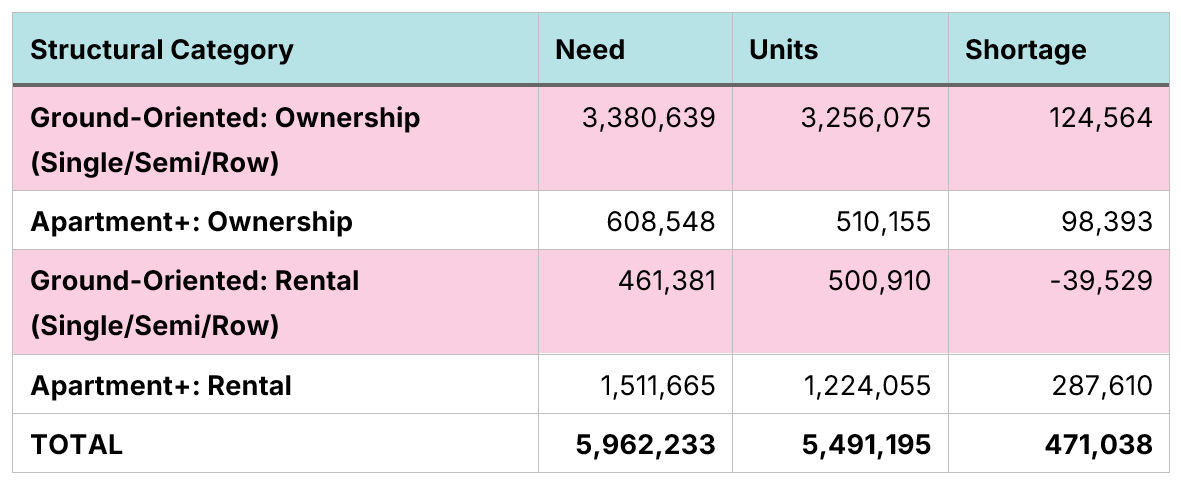

Using RoCA Benchmark 1.0, we estimated that, as of Census 2021, Ontario had a shortage of 471,267 units. Under RoCA 2.0, this estimate is now 471,038 units, with the small change coming from having more granular age categories.

As of Census 2021, RoCA 2.0 indicates that Ontario had large shortages of both rental apartments and ground-oriented ownership housing. Surprisingly, the benchmark also indicates that there were fewer apartment condos in Ontario than expected, given Ontario’s population size and age distribution. Conversely, in 2021, Ontario had more ground-oriented rental housing than the benchmark would predict. That is almost certainly due to Ontario having a much higher proportion of college and university students in 2021 than the average non-Ontario, non-British Columbia province had in 2016. It will be interesting to see how this figure changes in Census 2026, as a reduction in the number of international students may cause these homes to return to the ownership market.

Figure 7. Ontario’s Housing Shortage by Unit Category, as of Census 2021

We will be adopting this revised RoCA Benchmark to see how housing shortages have evolved, as well as show how the aging of Canada’s population will change the country’s housing needs over the next few decades. We hope other analysts will adopt this revised tool to move policymaking away from “a unit is a unit is a unit” thinking.

Download a PDF version of this article below:

In an ideal world, we would use housing completions rather than housing starts. Unfortunately, this is not possible at a province-wide level as the CMHC stopped collecting province-wide completions data in 2023. So, for most applications we use starts, rather than completions.

Yes, 5. Not a typo.