Legislation, Loans, and Lock-Ins: The Mechanics of Direct-to-Buyer DCs

Turning a wonky idea into a cost-saving reality

Highlights

Instituting a direct-to-buyer development charge system can save homebuyers tens of thousands of dollars in reduced tax-on-tax, interest charges, and junk fees.

The idea of implementing a system has begun to gain momentum, and the federal government can play a leading role.

Although the system itself is not particularly complicated, implementation will require all three orders of government to work together.

Several steps need to be taken to implement the system, including ensuring that DCs are rolled into mortgages (and not paid at closing costs), that DCs are exempt from HST and land transfer taxes, and creating instream protection to ensure that homebuyers are fully insulated from development charge increases during construction.

Development charges must be treated similarly to HST and rolled into a mortgage, rather than being paid at closing, as is the case with land transfer taxes in Ontario.

A wonky way to say homebuyers a lot of money

Despite (or perhaps because of) the piece's incredibly wonky nature, "How a Direct-to-Buyer Development Charge System Can Save Homebuyers $68,000," the piece was one of MMI’s most-read pieces, and the idea of a DC direct-to-buyer system is beginning to gain momentum. The Large Urban Centre Alliance of 13 Canadian homebuilders included the adoption of a Direct-to-Buyer development charge system as their second of ten recommendations to the federal government:

Substantially lower the price of new homes by removing tens of thousands of dollars of interest costs, junk fees, and tax-on-tax from the cost of new homes by implementing a transparent direct-to-buyer development charge (DC) billing model that exempts DCs from HST and land/property transfer taxes and provides in-stream homebuyer protection from DC increases.

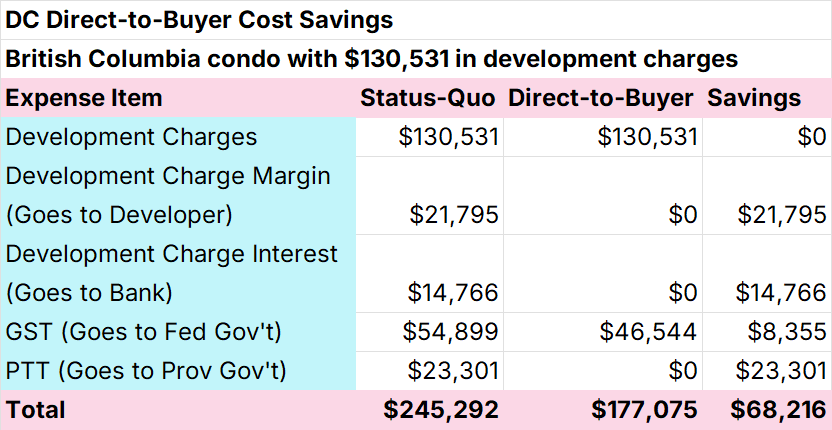

The idea is particularly attractive, as in our British Columbia example, it lowers the total cost to homebuyers by over $68,000, without any reduction in development charge rates; in fact, municipal development charge revenue increases in this model due to accelerated homebuilding. The magnitude of the savings is highly dependent on the type and price of the home, as well as where it is built.

Figure 1: Cost savings from a DC Direct-to-Buyer model, British Columbia example

Source: MMI

The novelty of the idea has naturally led to several questions about how the system works and what governments would need to do to implement it. While the system itself is relatively straightforward, the implementation does require some coordination between all three orders of government.

How homebuyers pay for development charges under the current system

Buying a home can be confusing due to the variety of taxes, fees, and charges, as well as the inconsistent use of the terms “price” and “cost”, which sometimes are used as synonyms, but other times differ substantially.

For example, the CMHC’s Homebuyers Checklist distinguishes between the purchase price of a newly constructed home, which is the price before GST/HST is applied, and the total cost of the home, which includes both the purchase price and the GST/HST.

Figure 2: Purchase price of a home vs. the total cost of the home

Source: Homebuyers Checklist

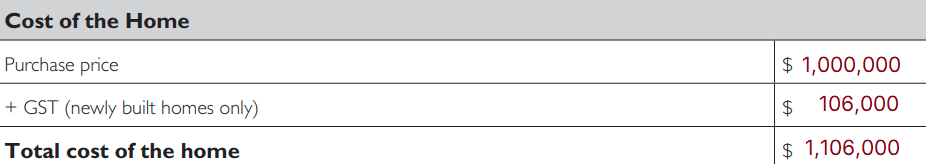

The GST/HST is calculated on the purchase price and is typically net of any rebates. Take the example of a newly constructed home in Ontario with a purchase price of $1,000,000. They would pay 5% in the federal portion of the HST, or $50,000, and not qualify for a rebate (with the exception of first-time homebuyers, who would qualify for the FTHB GST Rebate when it goes into effect). They would pay an additional 8% in the provincial portion of the HST, or $80,000, but qualify for a $24,000 rebate. After rebates, the total HST is $106,000. While the purchase price of the home is $1,000,000, the total cost is $1,106,000.

Figure 3: Purchase price of a home vs. the total cost of the home, example

Source: Homebuyers Checklist

This $1,106,000 represents the cost of the home, excluding any closing costs. The homebuyer will obtain a mortgage for this amount, less the size of their down payment.

The price vs. cost discussion gets confusing in Ontario because this $1,106,000 cost is typically presented to the buyer as the full price, which includes HST:

Newly constructed or substantially renovated homes in Ontario are subject to HST. If you're purchasing a new build, the price will generally include HST. However, it's essential to confirm this with the builder or your realtor to avoid any surprises.

Then, at (or just before) closing day, when the buyer takes legal posession of the home, there are closing costs, which are paid outside of the mortgage. In Ontario, these can be 3-4% of the house purchase cost, including substantial provincial and City of Toronto land transfer taxes, which are based on the purchase price of the home.

But where are the development charges under the current system?

The buyer never sees them, because they’re paid by the developer, who incorporates them into the purchase price. But they are real, and they are there. We outlined how these development charges cascade through prices in the piece How a Direct-to-Buyer Development Charge System Can Save Homebuyers $68,000:

In most development charge systems (sometimes referred to as “development cost charges”; we will use the acronym DCs), the developer pays for DCs and related fees when obtaining the building permit, typically using a construction loan that accrues interest as the home is being constructed. They then apply a markup (to meet the minimum profitability requirements of obtaining financing) to those DCs and the accrued interest, and embed those costs into the final price of the home. The buyer pays for the home upon legal possession, which, in the case of a condo, can be several years after the developer obtains the building permit. Because the DCs (plus interest and mark-up) are embedded in the final price, they are subject to GST, PST, and land transfer taxes (also known as property transfer taxes), creating a tax-on-tax situation. These cascading costs add tens of thousands of dollars in additional expense to the cost of a home.

In a purely legal sense, under the current system, the developer pays development charges that do not include GST, PST, and land transfer taxes.

However, in a practical or economic sense, the developer incorporates the development charges (along with the interest and margin requirements from DCs) into the purchase price. The purchase price, which includes embedded development charges, DC interest, and DC margin requirements, is subject to GST, PST, and land transfer taxes.

How would development charges work in a direct-to-buyer system?

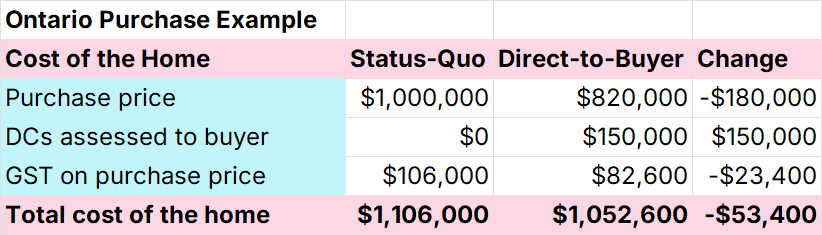

Instead of being embedded in the purchase price, they would be listed separately in the home's cost. The GST would still apply to the purchase price, but it would be lower now, as it would no longer incorporate development charges, DC interest, and DC margin requirements. For this example, the development charges are $150,000, with an additional $30,000 in associated interest/margin requirements.

Figure 4: Purchase price of a home vs. the total cost of the home, under status-quo and direct-to-buyer model

Source: MMI

Note that the total cost of the home to the buyer has decreased by more than $53,000, despite no change in the size of development charges.

Under the direct-to-buyer model, the development charges are treated like GST and are included in the mortgage (net of the down payment). They are not treated as a closing cost, unlike land transfer taxes in Ontario. In fact, closing costs are reduced in the DC direct-to-buyer model, as DCs would be made exempt from land transfer taxes.

The need for in-stream homebuyer protection from DC increases in a direct-to-buyer model

There are several challenges to adopting a DC direct-to-buyer model, with the most significant one being the ever-increasing nature of development charges. Consider the following scenario: At the time of signing the purchase and sale agreement, the development charges for the unit were $150,000. However, at closing, when development charges are remitted to the municipality, they have risen to $190,000, resulting in a $40,000 shortfall. There are three ways this could be handled, the first two of which create high levels of risk and discomfort:

The homebuyer is responsible for the additional $40,000 and must pay it at closing.

The developer is responsible for the additional $40,000.

The $150,000 amount is “locked in” when the purchase and sale agreement is signed, so neither party has to worry about future increases in development charges.

The value of the “in-stream protection” provided by option three cannot be overstated. The development charge rates that buyers pay must be based on the rate schedule that was in place at the time of the purchase and sale agreement, not at the time of closing.

What must governments do to implement a direct-to-buyer DC system?

Although a DC direct-to-buyer system is not particularly complex (and, in some ways, less complicated than the current system), it does require some coordination between all three levels of government, something that Canada is not particularly adept at. Here is what each order of government must do:

Federal government

Develop an agreement with provinces that the federal government will eliminate the HST on development charges in exchange for the province adopting a direct-to-buyer development charge system.

Exempt (not zero rate) development charges from HST.

Potentially provide compensation in the form of funding or loans to municipalities and provinces. While development charges themselves are not reduced in a direct-to-buyer model, the municipality receives their money at closing, rather than when issuing a building permit. This results in a slight reduction in interest revenue for the municipality and, in theory, could lead to cash flow issues when financing infrastructure. The federal government is well-positioned to assist municipalities and provinces with any transition costs.

Provincial governments

Amend their Development Charges Act (or equivalent) to adopt a direct-to-buyer model for development charges and any development-charge-like fee placed on ownership housing.

Amend their Development Charges Act (or equivalent) to create an “in-stream protection” clause to ensure that development charge rates paid are based on when the homebuyer signed the purchase and sale agreement, not based on the rates at closing.

Amend homebuyers' and consumer protection regulations to require homebuyers to be provided with accurate and detailed information on the development charges applicable to their new home, enabling them to make an informed purchase decision.

Exempt DCs from land transfer taxes, provincial sales taxes, and any other taxes placed on new housing.

Potentially provide compensation or adjustment support to municipalities.

Municipal governments

Ensure that homebuyers have full information about the development charges that they will be assessed.

Adjust infrastructure plans, if necessary, to account for development charges being paid at closing, rather than at the time of issuing a building permit.

This system is the beginning of a series of efficiency reforms, not the end

A DC direct-to-buyer system should be seen as the first in a series of efficiency-based reforms, particularly as it does not address purpose-built rentals. One of the real merits of the system is that it illustrates that reforms, including development-charge reforms, need not be zero-sum in nature. There is often a belief when discussing development charge reforms that anything that saves the homebuyer a dollar is one fewer dollar for governments. Nothing can be further from the truth. Through smart reforms, we can reduce waste in the system, particularly the billions in unnecessary interest costs that stem from an inefficient allocation of capital. Reforms should not be viewed as fewer dollars for government, more for the private sector (or vice-versa), but rather in creating more streamlined and efficient systems, where the private sector gains by being able to build more, governments get more tax revenue from increased building and economic activities, and more families get homes they can afford.