The City of Ottawa Needs More Family-Friendly Housing. Instead They're Contemplating Downzoning.

Two-storey maximums in urban areas and three in the suburbs is nonsensical.

Highlights

Annual housing starts in the City of Ottawa are less than half of the provincial target.

Over the last decade, the City has experienced substantial and increased outmigration of young families to surrounding communities due to the housing shortage.

The City has been rewriting its zoning bylaw, which is a prime opportunity to make the substantive changes needed to facilitate the building of more housing suitable for families with children, reverse the outmigration, and help hit the provincial target.

The proposed bylaw does contain a number of positive reforms around parking minimums and streamlining zoning.

The best places to allow more family-friendly density should be in neighbourhoods close to transit and other amenities.

Instead, the City is doing the opposite, limiting building height to two storeys in N1 and N2 urban neighbourhoods, while imposing a higher, three-storey limit in those neighbourhoods in the suburbs outside of the greenbelt.

Ottawa’s failure to enhance density in existing urban neighbourhoods is a case study in the power of local opposition and the Impossible Trinity of Housing.

Ottawa’s rezoning falls short

The City of Ottawa’s proposed new zoning bylaw has a pretty absurd feature—in single-family areas in urban areas close to transit, where increased density would make the most sense, the proposed bylaw imposes a two-storey height limit on buildings. But way out past the green belt, where transit is limited, the height limit is three storeys. This is not an accident; it is a feature of the Impossible Trinity of Housing.

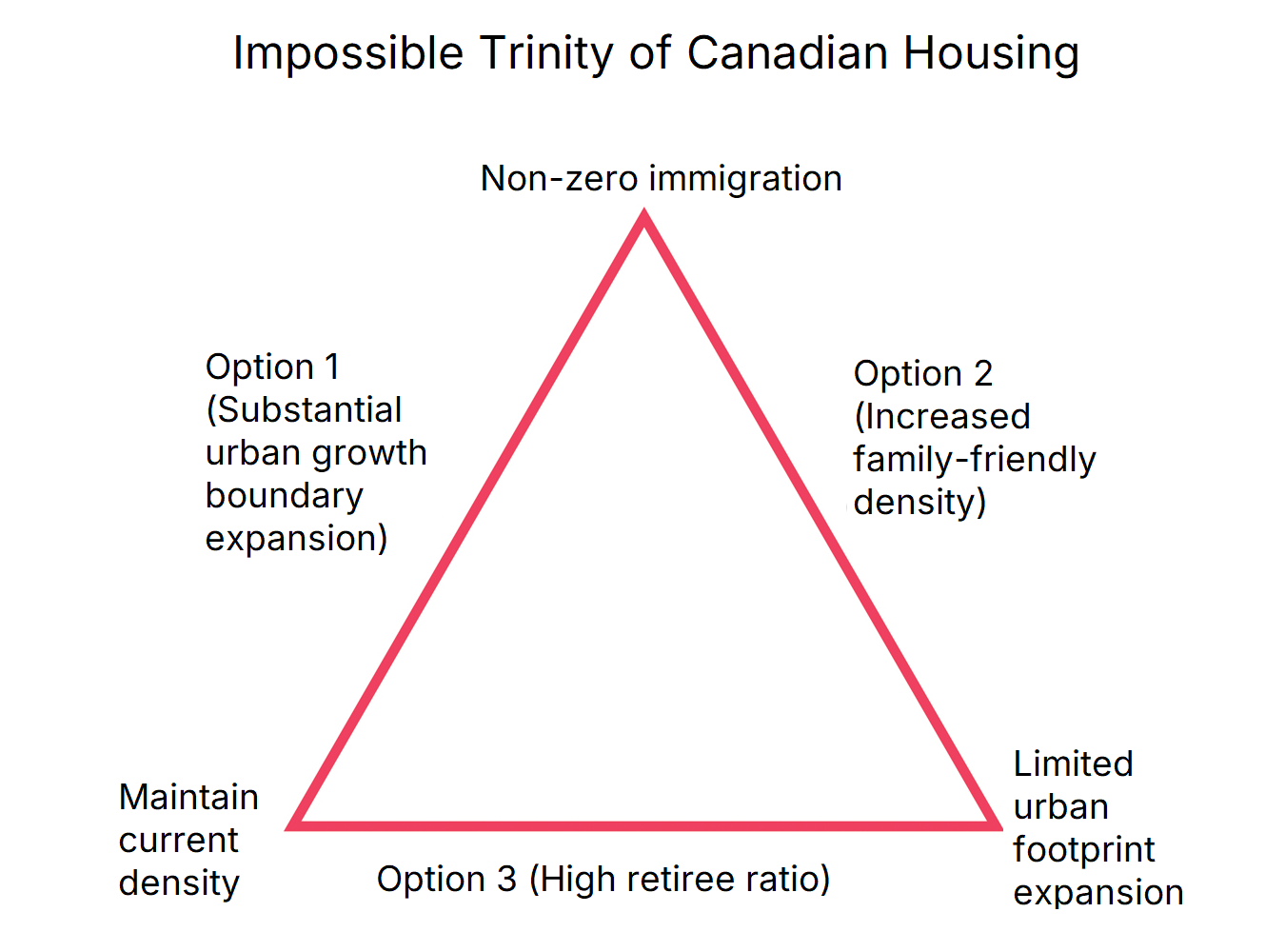

The Impossible Trinity of Housing states that there are three pathways to address a shortage of family-sized housing: Allow building outward through extending urban growth boundaries, legalize gentle density through changes to zoning policies, building codes and development charges, or cut population growth rates by reducing immigration rates or non-permanent resident programs. It also states that while achieving housing affordability through a triple combination of robust immigration, tight urban growth boundaries, and family-friendly densification is possible, it requires a level of discipline typically not seen across any order of government in Canada.

What makes the Trinity particularly challenging is that no one government controls all of the policy levers. Municipal governments, like the City of Ottawa, have no control over immigration or population growth policies, but can control urban growth expansion and density, subject to the limits placed on them through provincial legislation and any incentive agreements they have with the federal or provincial government.

Over the last two decades in Ontario, municipalities have largely engaged in a “triple strategy combination” by engaging in both limited (but non-zero) urban footprint expansion and limited (but non-zero) family-friendly densification legalization, while the federal government engaged in pro-population growth policies. However, the densification and urban footprint expansions were not large enough to meet the needs created by a growing population.

Many municipalities have understood the challenges created by population growth and have made good faith efforts to alter densification and urban footprint policies to meet the needs of a growing number of families. However, they have been unable to overcome local opposition and make their reforms meet the magnitude of need. This local opposition leads to watered-down reforms that appear like progress but ensure very little actually changes.

Ottawa provides the latest case study in this challenge, where the City of Ottawa’s proposed zoning bylaw places the largest restrictions on densification on neighbourhoods near transit. This includes two-storey height limits in some of the most desirable urban neighbourhoods in the city, while suburban neighbourhoods have a minimum of three storeys as of right across the board.

In short, the more urban the location of a single-family neighbourhood, the less the City of Ottawa’s proposed zoning by-law will let you build there. This will ensure that family-friendly three-bedroom homes remain unattainable to middle-class families in the City of Ottawa.

To understand how Ottawa’s new rezoning works, you need to know a little bit about the City.

Ottawa’s homebuilding is lagging behind

Due to the Mike Harris-era amalgamation, the City of Ottawa has an absolutely massive geographic footprint. Much of this land has not been made available for housing development. As with most Ontario cities, Ottawa has an urban growth boundary that limits the city’s urban expansion, and like most Ontario cities, expansions to this urban growth boundary have been highly contentious.

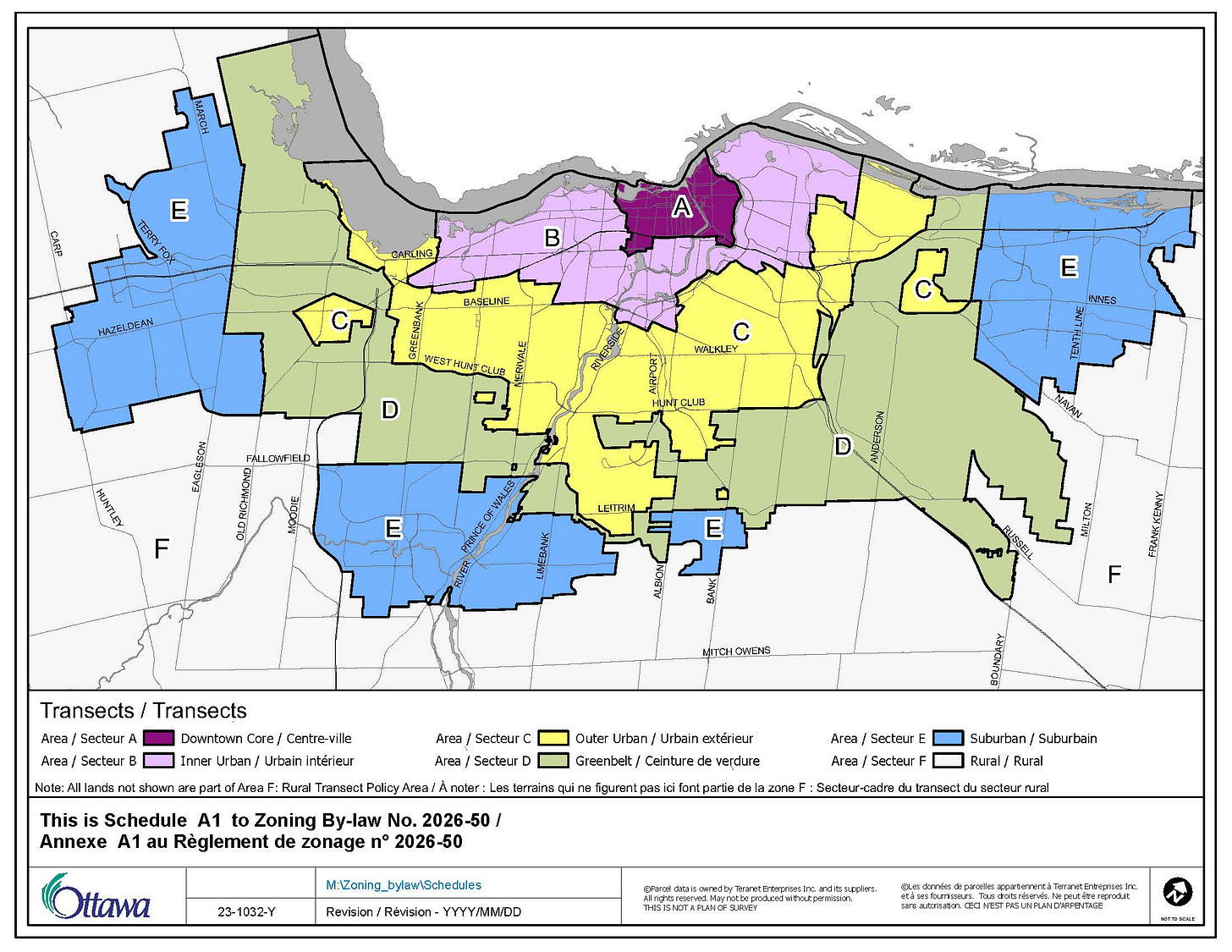

Unlike most Ontario cities, however, the City of Ottawa has a greenbelt running through it, shown on Figure 1 in green as Area D. This greenbelt divides the urban parts of the city (A, B, C) and the suburban parts (E).

Figure 1: Transects Map of the City of Ottawa

Source: New Zoning By-Law.

Also, unlike much of the rest of Ontario, Ottawa’s policy and economic conditions have allowed for the construction of some family-sized three-bedroom homes. Between 2016 and 2021, the number of owner-occupied three-bedroom homes rose by 3,140 in the City, about 7.5% of Ontario’s total increase, and the number of renter-occupied three-bedroom homes also rose by 5,205. Ottawa’s performance during this period greatly exceeded most other cities in Ontario, many of which saw the number of three-bedroom homes fall during this period, including in most of the GTA, Waterloo Region, Niagara Region, Middlesex (London), and Essex (Windsor).

However, that level of homebuilding still was not enough, given Ontario’s rapid population growth. Despite these additional three-bedroom homes, the City of Ottawa has experienced significant outmigration of young families to smaller neighbouring communities. This is in part due to the housing policy environment, which makes it challenging to build family-sized homes in the required quantity. These include (but are not limited to) zoning, high and rising development charges, and a broken urban growth boundary process.

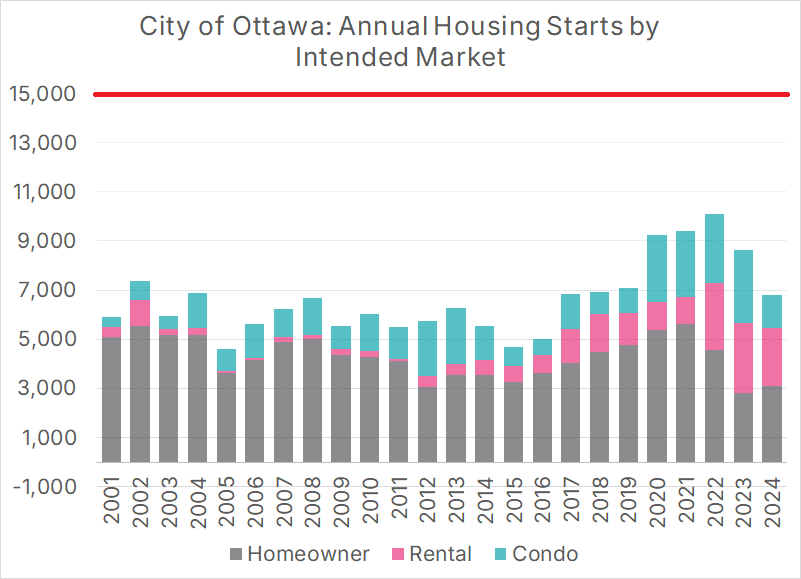

Regional population growth has outpaced homebuilding, so Ottawa’s home prices, while significantly lower than in many other parts of the province, remain at crisis levels. To address these housing shortages, the provincial government gave the City of Ottawa a housing start target of 151,000 units over a decade, or 15,100 a year. The City is nowhere near achieving this target, even for a single year. While the pace of homebuilding grew substantially after 2016, rising to just over 10,000 housing starts in 2022, it has since fallen dramatically, to 6,800 units in 2024, less than half the provincial target.

Figure 2: Annual Housing Starts by Intended Market, City of Ottawa

Data Source: CMHC Housing Market Information Portal.

The City needs to use every tool possible to meet the provincial target, and they have the perfect opportunity to use one of their biggest ones.

The City’s new draft zoning bylaw is a missed opportunity

Earlier this year, the City released the second draft of their proposed new Zoning By-law. There is much to like in the document, including four units as-of-right on every lot, and the elimination of parking minimums, a key recommendation of the Blueprint for More and Better Housing. To be clear, these provisions allow for builders to include parking or have fewer than four units on a lot if they wish, but ultimately, those decisions are left to the builder, rather than to the government. These moves have generated some controversy, including with municipal councillors.

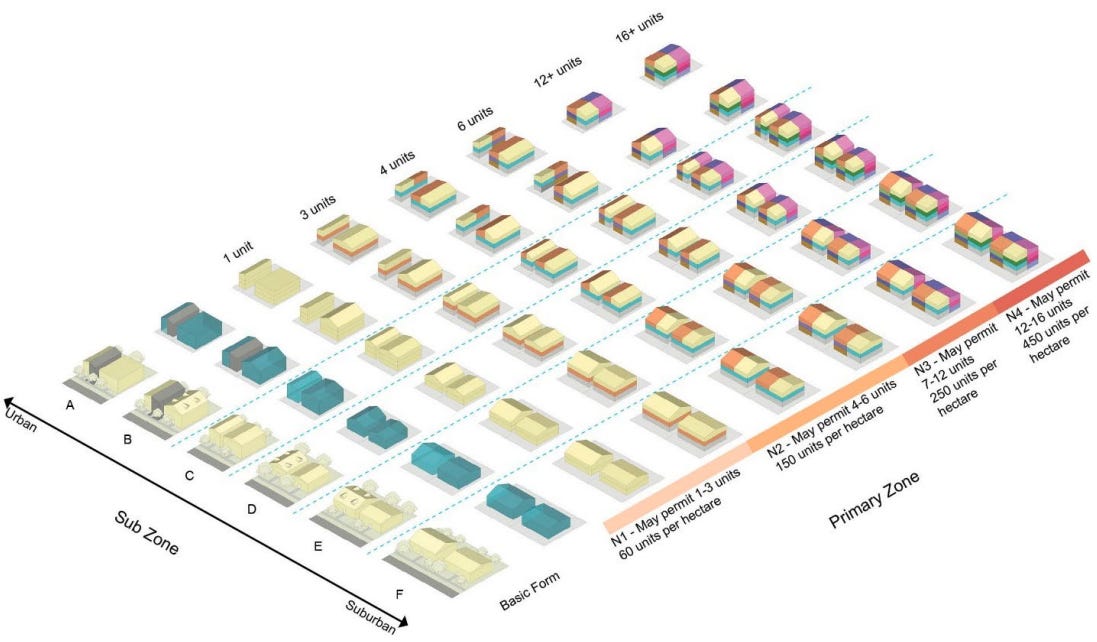

The proposed bylaw would also streamline the number of residential zones and subcategories from 140 variations and 600 subvariations to 36 neighbourhood combinations. There are six primary zones, which dictate building heights and maximum number of units per lot, and six subzones, which dictate features such as minimum lot widths. In theory, any combination of zone and subzone is possible; in practice, some combinations are unlikely to be used. As well, for any particular set of lots, there can be particular exceptions, such as height maximums that are higher or lower than what the zone would normally allow.

Figure 3: Primary Zones and Subzones, Proposed City of Ottawa Zoning By-Law

Source: New Zoning By-Law.

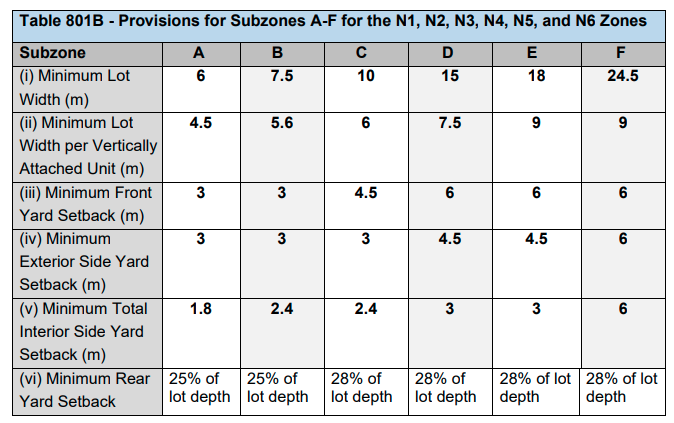

Starting with the subzones, we see that substantial variations exist between the six subzones, as the minimum lot width is over four times larger in subzone F relative to subzone A.

Figure 4: Primary Subzones A-F, Proposed City of Ottawa Zoning By-Law

Source: New Zoning By-Law.

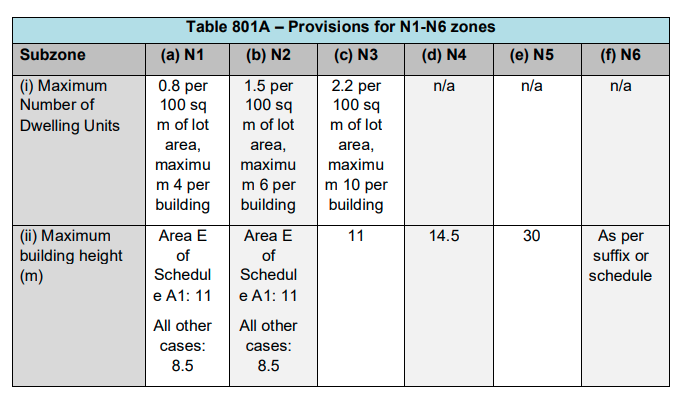

However, the real differences are in the zones themselves. The six zones differ by height limits, the maximum number of units per lot, and the maximum density of units. While the higher density N3 through N6 zones are consistent across the city (though individual units of lots may contain exceptions), the rules governing N1 and N2 differ by region.

In area E, the suburban area outside of the greenbelt, the maximum building height for N1 and N2 neighbourhoods is 11 meters, which corresponds to three storeys. But in the urban areas, which are closer to amenities and have more transit options, these neighbourhoods are limited to 8.5 meters, or only two storeys.

Figure 5: Provisions for N1-N6 Zones, Proposed City of Ottawa Zoning By-Law

Source: New Zoning By-Law.

Imposing a two-storey height limit on N1 and N2 makes it exceptionally difficult to build family-friendly density, such as tall-and-skinny duplexes, noting that many parts of urban and suburban Ottawa are zoned N3 or higher, where 11m (or more) is as-of-right across the city. For some properties with N1 or N2 zoning, the first draft of the proposed bylaws is more restrictive than the status quo, particularly in urban areas near transit—the exact places we should be trying to encourage gentle density.

During a housing and climate crisis, Ottawa’s proposed new zoning by-law actually downzones some urban areas. Why?

The City’s draft consultation is particularly revealing

Fortunately, the City of Ottawa has gone a long way to answer such questions.

The City deserves full grades for its transparency and outreach to the public. Substantial consultations have been held, and the City released a 336-page document summarizing those consultations and providing answers to residents. Not surprisingly, substantial opposition was expressed to many of the reforms that would allow for increased density.

This opposition, however, was not universal. A handful of residents were wondering why the City was not going further, including one resident who wondered why height limits were being kept so low:

A lot of the residential areas in the ward are zoned N1 or N2 where building height is capped at 8.5 metres which is about two storeys. This seems fairly low, especially if the intent is to have infill and building greater densities in residential areas. What's the logic behind locking the vast majority of the zoning in the residential areas to having a high restriction of two storeys (or 8.5 metres)? Is there a specific reason for that?

The City’s reasons were very clear: to protect the character of existing neighbourhoods and not to upset existing residents.

While the Official Plan allows up to 4 storeys citywide, the current approach to zoning and height assignment varies. One philosophy behind the eight-and-a-half-metre height limit is to reflect existing neighbourhood conditions, promoting context sensitivity in new developments. The proposed changes to neighbourhood zoning are more focused on reducing friction and eliminating the hidden complexities in the Zoning By-law, rather than universally expanding building envelopes. That’s not to say a more aggressive policy approach couldn’t pursue the full four storeys allowed by the Official Plan, but there are differing opinions on this. The emphasis on two-storey developments largely stems from the expectation that new buildings respect neighbourhood character and context.

This is not a one-off statement, as the consultation document references “character” 44 times. In many cases in the consultation document, when a resident asks a question about why the by-law is not more ambitious in allowing for densification, they are met with a response like this one on Page 290:

The limitations on multiuse properties in lower-density areas are primarily due to zoning rules that aim to preserve the character and scale of these neighborhoods. These rules often restrict the types of commercial and high density residential uses that can be introduced, to maintain a balance between development and the existing community fabric.

Wanting to “respect neighbourhood character and context” is one corner of the Impossible Trinity of Housing. The combination of robust population growth through immigration, maintaining neighbourhood character, and tight urban growth boundaries will lead to a failure of the housing system. Since the City has no control over immigration policy, it either needs to allow building out, or allow building up in a family-friendly way. By choosing to do neither at scale, it ensures the City’s shortage of family-friendly housing will persist.

Figure 6: Impossible Trinity of Canadian Housing

Source: The Impossible Trinity that Broke Canadian Housing.

The height limit issue has an obvious policy solution, but the underlying causes are more challenging

The obvious solution to the height issue is to increase the height limit to 11 meters in N1 and N2 zones across the City. Not surprisingly, this is the preferred solution of homebuilders. While that would be the right move (at a minimum), it does not address the policy pressures that led to the City placing such a restrictive minimum in the first place. Nor does it address the many other ways the proposed bylaw restricts family-friendly density, which we will cover in future pieces.

Download a PDF version of this article below: