Why is Toronto hoarding infrastructure dollars?

Money sitting in a bank account does not address crumbling infrastructure

Highlights

Municipalities in Ontario collect billions of dollars in development charges but don’t end up spending it.

This lack of spending was not “part of the plan” to allow reserves to build up to pay for larger pieces of infrastructure. On average, for every dollar of forecasted spending on infrastructure, Ontario municipalities have only spent 62 cents.

Toronto, in particular, has been hoarding development charge reserves. Between 2007 and 2023, the amount of unspent infrastructure money in Toronto's development charge reserves grew from $172 million to $3.1 billion, a 1,708% increase.

Toronto’s DC reserve fund exhibits an abnormal lack of outflow of money for infrastructure compared to other municipal peers like Ottawa, Barrie, and Hamilton.

A common response to our concerns that Toronto’s skyrocketing development charges are a leading contributor to the housing affordability crisis is that they are necessary, given the state of Toronto’s infrastructure. We would point out that higher development charge rates do not necessarily lead to more revenue and that cities are using some of that revenue on things other than infrastructure and unrelated to the cost of housing growth. However, we cannot argue about the poor state of Toronto’s infrastructure.

This then raises the obvious question: If Toronto desperately needs development charge revenue to pay for infrastructure, why is it going unspent?

We find ourselves in a paradox: Over a decade ago, Toronto’s infrastructure was being described as a crisis, yet the city seems in no particular hurry to spend the infrastructure dollars it has collected.

Toronto’s growing development charge reserves

Between 2007 and 2023, Toronto’s development charges reserves, money collected for infrastructure to support housing but not spent, increased from $172 million to $3.1 billion, a whopping 1,708% increase over 16 years.

Figure 1: Total Development Charge Reserves by Year – City of Toronto

Source: City of Toronto Annual Development Charge Reserve Fund Statements

Such a rapid increase should raise alarm bells or at least cause us to ask serious questions.

No, slow infrastructure spending and growing reserves are not “all part of the plan”

And, occasionally, someone does ask those questions. A commonly cited explanation for Toronto’s growing development charge reserve fund is that revenues are collected before construction begins, and those reserves are drawn down as construction is completed. This was the explanation that (then) Mayor John Tory gave in 2022 when asked about the city’s ballooning DC reserve fund:

“Yes, the City has development charge reserves and they have a lot of money in them, and that is because we collect the development charge but we’re not necessarily building the sewer pipe or building the road or building the transit project that day… and so it is a legal obligation that we keep that money in a reserve fund, not some kind of bank account that’s like a piggy bank.”

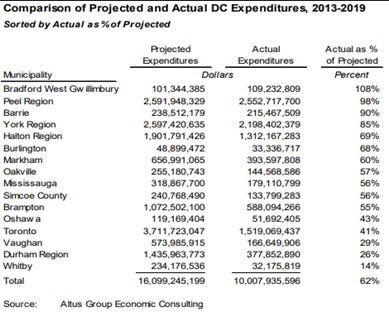

This would suggest that growing reserves were “part of the plan” and that the city had not intended to spend this money yet. We know, however, that this isn’t true. Between 2013 and 2019, the City of Toronto, like many other cities in the Greater Toronto Area, fell short in planned infrastructure spending from DC reserves. While the City of Toronto had planned to spend $3.7 billion on infrastructure from DC reserves, actual expenditures were only $1.5 billion, less than half of what was projected.

Figure 2: Projected vs Actual DC Expenditures, 2013-19

Source: Altus Group

It isn't easy to reconcile these numbers with the idea that ballooning development charge reserves are nothing to be concerned about.

In Toronto, DC reserve funds are rarely drawn down

The logic of DC reserve funds is that a substantial portion of the money needed for large infrastructure projects is collected up front, so revenues exceed expenditures and reserve funds rise. However, once those big projects get underway, expenses are paid against those funds, and the reserve funds are “drawn down” and get smaller. All reserve funds are supposed to net out to $0 over a planning horizon period, which is typically 10 years for most types of infrastructure services (e.g. police, roads, transit, etc.).

In other words, there should be years when the size of reserve funds increases and years when it decreases.

In many municipalities in Ontario, reserve funds are drawn down. But this is very rarely the case for the City of Toronto.

For example, we can compare Toronto to other single-tier municipalities that cover similar service offerings, like Barrie, Ottawa, and Hamilton. In the 14 years where data is available, Barrie had nine out of 14 years where DC reserve funds shrank, Ottawa had five, and Hamilton had three. This is roughly the behaviour you’d expect to see if reserve funds were routinely drawn down.

The City of Toronto, on the other hand, only had one year, 2017, in which reserve funds were smaller at the end of the year than they were at the beginning. This drawdown was relatively small in magnitude relative to the increases in other years.

While Toronto is an outlier in the data, they are not alone.

Growing DC reserve funds is not just a City of Toronto phenomenon

The amount of money sitting in development charge reserves across Ontario’s municipalities grew from $2.6 billion to $10.7 billion between 2010 and 2022.1 This equates to a 316% increase over 13 years, which is incredibly high yet still lower than Toronto’s 891% increase during the same period.

Figure 3: Total Development Charge Reserves – All Ontario Municipalities

Source: Schedule 61 of Ontario’s Municipal Financial Information Return and Annual Development Charge Reserve Fund Statements

Toronto is hardly alone among municipalities that have collected development charges but left them unspent, resulting in ballooning reserves. As Figure 2 shows, very few municipalities in the GTA have been meeting their spending projections.

However, it is disproportionately a City of Toronto phenomenon

Of the $10.7 billion in reserves in the province, $2.7 billion (25.4%) of it belongs to the City of Toronto, the largest share of any municipality in the province. While you’d expect Toronto to have the largest funds in reserves given it is the largest city in the province, this wasn’t always a fact.

Back in 2010, Durham Region, Ottawa, and York Region all had larger development charge reserves than Toronto. Reserves in those cities have also grown, but nowhere near the rate they have in Toronto: 234%, 105%, and 32%, respectively, for the three municipalities between 2010 and 2022.

Toronto’s escalating reserves stand out among Ontario municipalities for reasons policymakers have never adequately explained.

Municipalities would do us all a favour by adopting the best practice of showing their annual reserve plans, which include forecasted DC revenue, expenditures, and reserve size by year. Furthermore, annual reserve statements should include a comparison between forecasted and actual infrastructure spending.

We need better answers

There are many possible explanations for why the City of Toronto and other communities in Ontario are allowing development charge reserves to balloon amid large infrastructure deficits. However, given the poor quality of Ontario municipal data and the background reports necessary to do this work often being removed from municipal websites without a trace, it is simply not feasible to do this work. This is one reason why the Missing Middle Initiative is seeking to create a repository of these documents.

However, even if the data and documents were available, no one is currently regularly reviewing and auditing infrastructure delivery. There has never been a provincial audit of the current development charges system since its inception in 1997, almost thirty years ago. While there was a proposed audit in 2023, the results from this work have not been publicly released.

Thankfully, for the City of Toronto, we may be getting some answers to the question of Toronto’s massive and growing DC reserve fund. The City of Toronto Council passed a motion in early February 2025 asking that:

…the Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer to initiate a comprehensive review of development charges which incorporates the City’s growth-related capital requirements, enhances the flexibility to leverage development charge funding across all eligible capital projects, and considers housing affordability and market trends.

It remains to be seen whether this project will succeed and provide valuable insights, but it is at least a step in the right direction.

Download a PDF of this article here:

2022 being the most recent year for Ontario-wide numbers, a damning indictment about the timeliness of municipal data in Ontario.