British Columbia Can Substantially Lower Housing Costs with One Simple Trick

Charging DCCs as a separate tax can reduce "junk fees" by tens of thousands of dollars

Highlights

Previously, we showed that development cost charges (DCCs) and similar charges (community amenities charges), the GST and property transfer taxes (PTT) add over $250,000 to the price of a Vancouver condo.

Nearly $12,000 of the $250,000 from tax-on-tax, GST and PTT charged on development charges.

Over $36,000 of the $250,000 comes from the equivalent of “junk fees” - interest costs and margin requirements on developers stemming from how DCCs are structured and timed; essentially pure waste.

Governments have several options to reduce housing taxes, including enhanced GST and PTT rebates, as well as discounts on development charges.

Governments could also defer DCC payment to the end of a project, which would help reduce junk fees through reduced interest costs.

The biggest cost reductions would result from a regulatory change that treats development charges as a separate tax item, rather than incorporating them into housing costs. In our example, it would provide a savings of $68,216, which includes an elimination of junk fees ($36,560) and the elimination of the development charge tax-on-tax ($11,696).

We have developed a free-to-use British Columbia Housing Construction Tax Calculator to allow others to design their own tax reforms and scenario analyses, including development charge reforms and enhanced GST and PTT rebates.

A how-to guide on addressing the cost-of-delivery crisis

In How Taxes, and Taxes-on-Taxes Add Over $250K to a Vancouver Condo, we saw how a series of municipal development cost charges (DCCs) and community amenity contributions increase the minimum price for a sample new condo from just under $1.1 million to over $1.35 million.

Figure 1: Price components of a sample newly constructed Vancouver condo unit

Source: How Taxes, and Taxes-on-Taxes Add Over $250K to a Vancouver Condo

There are three important things to note about these numbers:

The $250,000 in extra costs do not include all taxes and fees; for example, permitting fees and the property taxes paid prior to completion are not listed, so the full tax and fee burden is even higher.

Not all of the $250,000 in extra costs goes to governments. Over $36,000 of these costs is attributed to interest expenses on those development charges, as well as the fact that DCCs are included in cost calculations, which impact the minimum profitability requirements placed on developers to obtain financing (listed as “margin requirements”). These are the housing cost equivalents of “junk fees”, which result from the timing and structure of municipal fees, and should be considered a form of waste.

The total cost to buyers of $1.35M should be considered a price floor. It is true that in a hot real estate market, a developer may receive a higher price than this (and therefore a higher profit margin). However, this is as low as the price can go; any lower and the developer will be unable to access financing from a lender. Which means that if there are not enough buyers at this price point, the building will not be constructed. If we want prices to decrease while continuing to build homes, we need to lower this price floor, which can only be achieved by reducing costs, including taxes.

Governments are increasingly recognizing that taxes and fees on new housing construction are too high, and groups like ours have suggested several reforms. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to know how these reforms will impact the price of a home or compare one potential reform to another.

Let’s fix that.

Our brand-new British Columbia Housing Construction Tax Calculator enables users to input details about a project and design particular tax and regulatory changes, including development cost charge reductions and enhanced GST and PTT rebates, to see how they impact the final price of a project.

For our Vancouver condo example, the best bang-for-the-buck reform, by far, is to treat development costs and related charges like the GST and PST; that is, assessing them to buyers at the end of a project, and not subjecting them to other taxes. It provides a savings of $68,216, which includes an elimination of junk fees ($36,560) and the elimination of the development charge tax-on-tax ($11,696).

Let’s walk through the math and examine a series of options.

Option 1: Enhanced GST rebate (Savings: $29,721)

The simplest and fastest way the federal government could reduce the cost of housing is by enhancing the pre-existing GST/HST New Housing Rebate. The federal government is proposing to raise the lower threshold from $350,000 to $1,000,000, increase the upper threshold from $450,000 to $1,500,000, and raise the maximum rebate from 36% to 100%, but only for first-time homebuyers. MMI is one of many groups that believe that the first-time homebuyer restriction on this proposal should be removed.

If the federal government enacted this reform and made it available to all buyers of primary residences, the savings would be just under $30,000 per unit. The entire savings would come from reduced per-unit revenue flowing to the federal government, noting that they will recoup a portion of the lost revenue through increased building and spin-off economic activity.

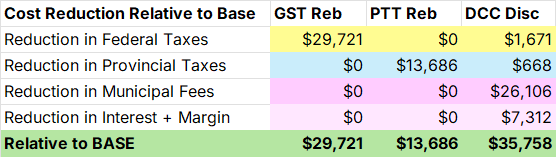

Figure 2: Savings from an enhanced GST rebate

Source: Author’s Calculation

The thresholds for the rebate are somewhat arbitrary, and choosing different thresholds (or rebate rates) will result in varying levels of savings. A full 100% rebate on the entire cost of the home would yield a rebate of $63,253.

We can conduct a similar exercise with the provincial property transfer tax (PTT).

Option 2: Enhanced PTT rebate (Savings: $13,686)

The current provincial PTT rebate for new housing has a 100% rebate rate, a lower threshold of $1,100,000 and an upper threshold of $1,150,000. Let’s raise that upper threshold to $1.5 million, to be aligned with the proposed GST rebate. This would save the buyer $13,686 in provincial tax.

Figure 3: Savings from an enhanced PTT rebate (PTT Reb Scenario)

Source: Author’s Calculation

To aid in comparison, we have left the GST Rebate savings on the chart. This piece will add rebates to the chart one at a time; however, note that they should be considered as separate initiatives, and the savings should not be “added together”, as implementing multiple policy reforms at once can cause interaction effects.

As before, the choice of thresholds is somewhat arbitrary and could be changed. The maximum possible rebate on this unit would see a savings of $23,301 in provincial taxes.

Now that we’ve analyzed a federal and a provincial tax cut, let’s turn our attention to municipalities.

Option 3: 20% Reduction in DCCs and CACs (Savings: $35,758)

Over half of the taxes and fees we identified for our Vancouver condo come directly from municipal development cost charges and related fees, making them an obvious place to look for savings. In Ontario, Mississauga and Vaughan have lowered development charges, and the federal government has proposed a program that would require municipalities to lower development charges on multi-unit residential buildings by 50% in exchange for federal funding.

The savings here can be substantial. Even a 20% reduction in development charges can yield savings of over $35,000, as shown in Figure 4.

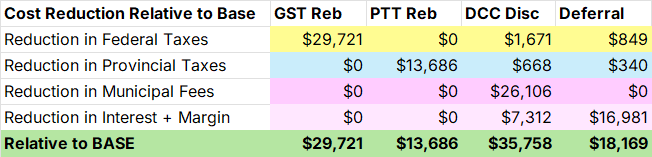

Figure 4: Savings from a 20% reduction in DCCs and CACs. (DCC Disc Scenario)

Source: Author’s Calculation

Although the buyer saves over $35,000, the municipality loses only $26,000 per unit from the change. Because DCCs are embedded into the price of a house, a lower home price means less GST ($1,671) and PST ($668) payable.

There is also a significant cost reduction from waste.

Developers pay development cost charges and other related fees at the beginning of construction. In our example, these fees are just over $130,000 a unit, totalling over $9.6 million on the 74-unit building.

These fees are debt-financed, so the developer must obtain an additional $9.6 million in financing. Assuming the project is financed for 28 months, at a construction loan rate of 4.7%, the developer pays the lender over $1 million in interest to cover these fees.

But that is not the end of the costs. Because the developer must incur an additional $9.6 million in debt, the project must generate higher projected profits, as lenders require a minimum profit margin to be willing to fund the project. This is noted in Figure 4 as “Margin”.

Totalled together, the additional interest expense and margin requirements amount to $36,560 per unit, or $2.7 million for the project. This is pure waste. The developer acts as a flow-through entity, as they ultimately pass these costs along to the end buyer, who is forced to pay these additional junk fees. Not only that, but the homebuyer also has to pay GST and PTT on those junk fees; a tax on junk. That is a significant expense to the buyer, for which they derive zero benefit. There is also little benefit to the government, other than receiving their development charges sooner than they would otherwise. Municipalities can earn some interest on these fees, but the interest rate they receive is far lower than what a lender charges to a developer.

Tying up $9.6 million in working capital is pure waste. But there are ways it can be corrected. Reducing development charges is one way; in our 20% DCC reduction scenario, these junk fees are reduced by $7,312 a unit. Another way is through deferring development cost charges.

Option 4: DCCs deferred to occupancy permit (Savings: $16,981)

If governments defer development charges to occupancy, it reduces interest expenses by $16,981, a massive reduction in junk fees. Because those fees are passed along to the homebuyer, there are also small reductions in GST ($849) and PTT ($340), resulting in a total savings of $18,169.

Figure 5: Savings from a zero-interest deferral of DCCs and CACs to closing. (Deferral Scenario)

Source: Author’s Calculation

Unfortunately, because the DCCs show up on the developer’s balance sheet as a cost, they do impact the minimum level of return the project needs to obtain funding, as the developer is still acting as a flow-through entity. So, junk fees have not been fully eliminated.

However, there is a simple solution to this problem: have development cost charges bypass the developer entirely by having them appear as a separate line item on the price of the home, paid for by the buyer.

Option 5: DCCs charged to buyer, rather than developer, but DCCs still included in GST and PTT calculations (Savings: $39,120)

By bypassing the developer entirely and having the homebuyer pay for DCCs at closing, we can eliminate the interest and margin junk fees. In this example, the buyer must still pay GST and PST on DCCs, but there is a small reduction in GST ($1,828) and PST ($731) payable due to the elimination of junk fees. The total savings are just over $39,000.

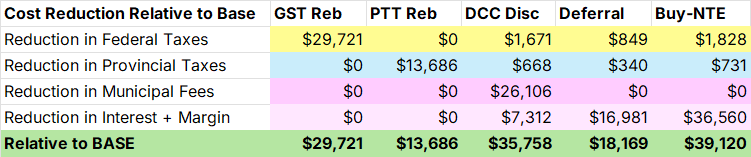

Figure 6: Savings from DCCs charged to the buyer, rather than the developer, but DCCs are still included in GST and PTT calculations (Buy-NTE Scenario)

Source: Author’s Calculation

Finally, we can take this one step further. We can have the buyer pay DCCs at closing and exempt those DCCs from GST and PTT.

Option 6: DCCs charged to buyer, rather than developer, and exempted from GST and PTT (Savings: $68,216)

In this scenario, the savings increase dramatically, as excluding DCCs from GST and PTT calculations increases the savings from $39,120 to a whopping $68,216!

Figure 7: Savings from DCCs charged to the buyer, rather than the developer; DCCs are exempt in GST and PTT calculations (Buy-TE Scenario)

Source: Author’s Calculation

Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed the massive savings in this scenario from provincial PTTs, with the reduction in provincial taxes rising from $731 to $23,301 by simply exempting DCCs from the tax calculation. In fact, in this scenario, the buyer pays no net PTT whatsoever!

The massive drop in PTT is due to the fact that by exempting DCCs from the tax calculation, we have dropped the sticker price of the home to just under $1.1 million, which then makes it eligible for a full PTT rebate, which has a $1.1 million threshold. This is a prime example of how different parts of the housing tax system interact with one another.

As with the previous example, there is also a reduction of $36,560 in interest and margin expenses; thus, this is not just a tax reduction, but also a reduction in junk fees through more efficient design.

Governments have lots of different options to lower taxes on homes

Homebuilding has a cost-of-delivery crisis, and governments must find innovative ways to reduce these costs if they are to tackle the housing crisis effectively. Tax reform is a prime way to reduce costs, although there are numerous ways to achieve this. We have presented six options, but many more are possible. When the government is considering lowering housing construction taxes, it should not treat the exercise as a zero-sum game (that is, one fewer dollar for the government and one more dollar for the home buyer). The zero-sum mindset overlooks the fact that lowering costs can lead to increased homebuilding. But, as importantly, tax reform can also make the system more efficient by reducing “junk fees” that are of no value to either the buyer or the government.

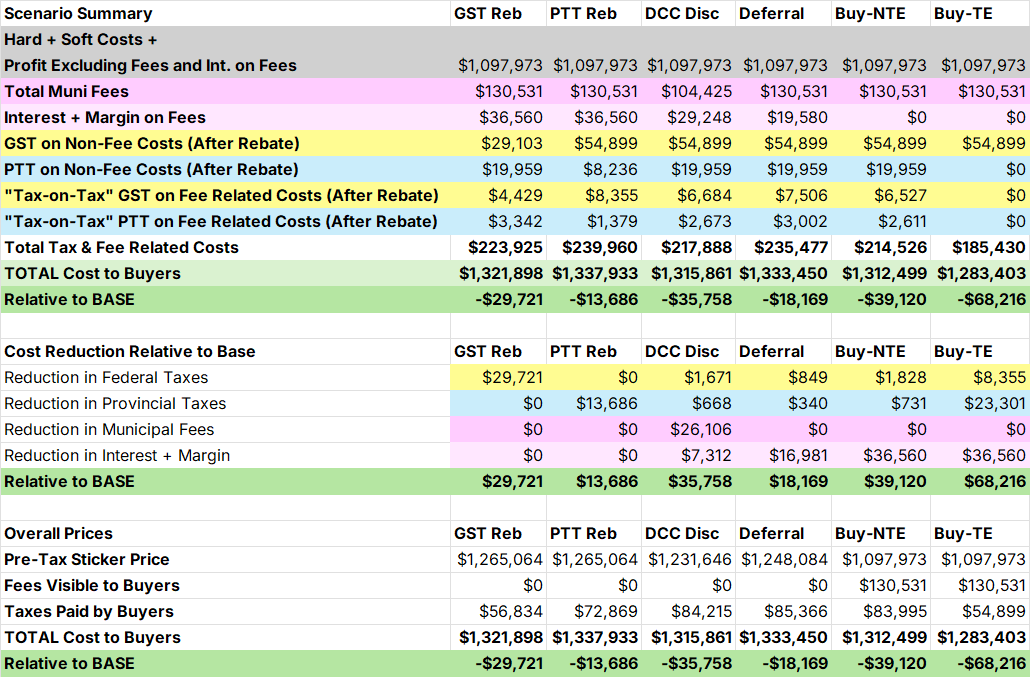

Figure 8: Summary of Scenarios

Source: Author’s Calculation

In terms of sheer bang for the buck, having governments assess development charges directly to the end homebuyer, rather than using developers as a flow-through entity, creates the best value. This approach creates a far more efficient system by lowering financing costs and related junk fees, a reform which would benefit both homebuyers and homebuilders.