Halving DCs Won’t Survive the Political Math

A case study of three provinces

Highlights

Development charges (DCs) need to come down, and the federal government’s plan to compensate municipalities to halve DCs is well-intentioned.

The plan, however, would see almost all the compensation go to the Greater Vancouver and Toronto Areas (GVA and GTA), which is politically untenable.

DCs in Ontario and BC are, in part, disproportionately higher than Alberta because of choices regarding how many services they allow their use for, and how extensively local municipalities choose to use this taxation capability. An across-the-board reduction does not account for this reality.

DC relief will also be a problem if it only compensates municipalities. This would penalize jurisdictions, such as Edmonton, that have established municipal service corporations (MSCs) to handle infrastructure planning and financing, thereby limiting the need for or use of DCs.

Any federal program will also have to account for all available growth funding tools, not just DCs, to be vigilant that municipalities do not use alternative housing taxes to make up for lost funding from reduced DCs.

There are ways to create DC reduction plans that are regionally fair. The most productive place to focus on addressing DCs is where there is the most universal applicability, like with enhancing the gas tax or promoting the adoption of direct-to-buyer DC policies, among other options.

National dollars, regional winners

High and rising development charges are harming housing affordability, so the federal government’s commitment to compensate municipalities to cut their development charges (DCs) in half for multi-unit residential housing should be welcome news. However, despite the federal government’s best intentions, the plan is likely to be political untenable as almost all of the money would go to the Greater Vancouver and Toronto Areas (GVA and GTA), as those two areas have both disproportionately high DCs and high levels of multi-unit construction.

The high DCs in these two regions are not an accident of nature but instead reflect both policy choices that individual provinces have made around constructing their various growth funding regimes1 and, in turn, how local municipalities have decided to implement them. Trying to create a national program that provides substantive benefits across the board creates lopsided benefits for specific regions of the country at a cost to everyone else.

To illustrate some of the disparities in policy frameworks, we’ve chosen to examine three major provinces and three major aspects of growth funding regimes. Those provinces are Alberta, British Columbia (BC) and Ontario, and the aspects are DC Service Eligibility, Alternative Entities, and Alternative Growth Funding Tools.

Charting eligibility

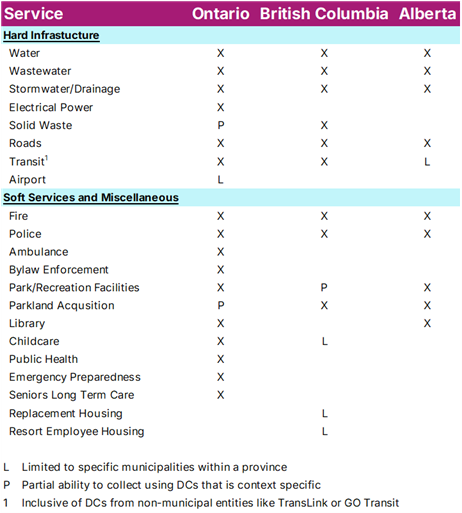

A chart comparing DC service eligibility by province is going to necessitate glossing over some nuances, but three things become immediately apparent from our Development Charge service eligibility chart (Figure 1):

Ontario allows DCs to be used for a wider range of services compared to either Alberta or BC.

Alberta limits its use more than either Ontario or BC, particularly with big-ticket, hard infrastructure items like transit and solid waste.

How few similarities in service eligibility there are between these three provinces altogether.

Figure 1: Development Charge service eligibility chart

Source: MMI

While there is more similarity between provinces in hard infrastructure than in soft, even within this service category, there are significant differences between just three provinces. Additionally, not all municipalities take advantage of every service for which they are eligible to collect DCs, or when they do collect them, they may not utilize them to the same extent as a peer does for the same service.

For example, Alberta only allows DCs2 to be collected for a very narrow set of services, but also gives Calgary and Edmonton a wide latitude to define for themselves what infrastructure DCs can be collected for. Calgary exercises its powers to charge DCs for services like transit, which other municipalities in Alberta can’t set a fee for, while Edmonton doesn’t use its expansive authority at all, solely collecting for fire infrastructure, which any municipality in Alberta can do.

There are also situations where DCs can only be used by a limited number of municipalities, as in the case of Calgary with its transit system or Vancouver with rental replacement housing.

In other situations, all (or most) municipalities in a province can collect a DC for a service, but what they can collect only covers a limited scope of capital costs. For example, in Ontario, municipalities can charge for waste services (garbage), but not for costs related to landfill sites or incineration plants.

DCs in Ontario and BC are, in part, disproportionately higher than Alberta because of choices regarding how many services they allow their use for, and how extensively local municipalities in particular regions choose to use the taxation capabilities granted to them. A federally compensation program based on an across-the-board reduction does not account for this.

Alternative entities

Municipalities are not the only entity that collects DCs or manages the funding of local infrastructure. In BC and Ontario, regional transit agencies such as TransLink and GO Transit can collect DCs to fund equipment and infrastructure. In all three provinces, school boards can also collect DCs from new homes or through alternative taxation means.

There are also municipal service corporations (MSCs), like Edmonton’s EPCOR, which is responsible for providing water, wastewater, electricity, and natural gas services, or Toronto’s Toronto Hydro, which provides electricity services. If DC relief is only provided to municipalities, it would penalize jurisdictions, like Edmonton, that have set up MSCs to deal with arms-length infrastructure planning and financing, which in turn limits the use or need for DCs.

Alternative growth funding tools

Figure 1 only examined DCs; however, there is a problem with viewing infrastructure financing narrowly this way because, as we love to say at MMI, DCs are one of an alphabet soup of housing taxes.

Just because a specific service is eligible for DCs in one province but not another does not mean there aren’t other forms of housing taxation available to help pay for it. Every province offers a range of alternative growth funding tools to municipalities, which can help cover the cost of infrastructure.

For example, in Ontario, Community Benefit Charges (CBCs), which are a parallel housing tax to DCs, allow the taxation of up to 4% of land value from high-density projects. Municipalities are allowed to use CBCs to pay for almost any service3 that their imaginations can conceive of, including services that DCs pay for4.

Another similar tax in BC is Amenity Cost Charges (ACCs), which, like CBCs, are meant to work in tandem with DCs in that province. However, ACCs are more limited than CBCs as they’re restricted to a service that provides social, cultural, heritage, recreational or environmental benefits to a community5, which is still quite an open-ended scope.

Alberta is the most restrictive when it comes to allowing the use of alternative growth funding tools, particularly with its regime surrounding community reserves (CR), which can only cover very specific soft services. Also, to get funding into a community reserve, it must come through selling surplus municipal and school reserve (MSR) lands6 that homebuilders provide through the subdivision process, which is a far more complicated and convoluted path than what it takes to generate funding using a CBC in Ontario or an ACC in BC.

With these examples, Ontario is once again at the farthest end of the spectrum in terms of allowing municipalities a wide latitude to use alternative methods of housing taxation to pay for services, often with a dubious relationship to growth, BC being not far behind, and Alberta at the other end of the spectrum with very tight restrictions on the ability to generate funding and use the monies collected.

A promise to halve development charges does not take any of this into account, and, if poorly designed, municipalities could use these other funding tools to offset any reductions in DCs, allowing them to obtain federal funding and continue to tax new housing construction at the same rate. If this were to happen, a federal program to cut development charges would run into the same challenges as the Housing Accelerator Fund (HAF), where municipalities have often come close to violating the spirit, if not the letter, of agreements.

It doesn’t have to be perfect, but it does need to be fair

The federal promise to halve development charges, as is, is unworkable, but there are alternatives. The most productive place for the federal government to focus on addressing DCs is where there is universal applicability, like with enhancing the gas tax or promoting the adoption of a direct-to-buyer DC policies. It is possible, through creative program design, for the federal government to lower municipal housing construction taxes while simultaneously ensuring the initiative is fair across regions.

Download a PDF of this article here:

Policy frameworks that include development charges and the alphabet soup of other fees and levies.

Called Redevelopment or Offsite Levies (OSLs) in Alberta.

CBCs must demonstrate that a service is related to growth, but there are clear cases of loose adherence to this requirement.

CBCs can be used to pay for the same service but not the same specific things as DCs, e.g. both can pay for a playground at a specific park, but a CBC cannot be used to pay for the slide that a DC is paying for, but it can be used to pay for the jungle gym if DCs aren’t being used for it.

Local Government Act section 570.1.

As part of the subdivision process, a homebuilder can be required to dedicate up to 10% of the land of a site for municipal and school reserves.