New Homes are the Solution: Policy Must Treat Them Differently

Failure to distinguish between new and existing homes leads to poorly design public policy

Highlights

Governments across Canada are looking to increase the supply of new housing.

Unfortunately, housing policies often do not distinguish between new homes and pre-existing homes, which can lead to two large unintended consequences.

The first unintended consequence is decreased affordability through policies that increase the demand for all housing.

The second unintended consequence is reduced home construction through policies that block investment in housing construction.

These are solvable problems. For example, Australia has exempted new homes from their foreign buyer ban to attract much-needed investment capital.

Increasing the supply of new homes vs. allocating the existing stock

Governments across Canada are focused on increasing the supply of new housing, as they have correctly recognized that there is no solution to the housing crisis that does not involve increasing the rate of housing construction. However, housing policies from all three levels of government often do not distinguish between new homes and existing homes, which can lead to two large unintended consequences: decreased affordability through stoking demand, and reduced supply through choking off much-needed investment.

Addressing the cost-of-delivery crisis vs. adding demand fuel to the fire

The combination of increased affordability and robust supply growth can only come by addressing the cost-of-delivery crisis. These costs of delivery include everything from the cost of construction to the cost of land to the cost of various taxes, fees, and charges.

Lowering construction costs increases the viability of home construction, leading to more homes being built. This increase in the housing supply puts downward pressure on both new and existing homes, as they compete with each other in the marketplace. Similarly, as construction costs go up, so too does the price of new and existing homes. Take municipal development charges, for example. High and rising development charges make some projects unviable, causing housing construction to slow, putting upward pressure on new and existing homes.

Governments can address the cost-of-delivery crisis by cutting housing construction-related taxes. The linkage between these taxes and construction is not always obvious. The GST on housing, for example, is, at its core, a housing construction-related tax, as it only applies to newly-built homes. By enhancing the GST New Housing Rebate, the federal government can lower the cost of homebuilding and enhance affordability.

The GST New Housing Rebate contrasts with affordability policies that are agnostic to whether the homes are new or preexisting, such as the federal First-Time Home Buyers’ Tax Credit. Because the tax credit does not target the cost of construction, it simply adds more demand to the system without an increase in supply, leading to higher prices, though it does so in a way that advantages first-time homebuyers over other groups.

In short, there is a fundamental difference between lowering the cost of new builds and boosting demand for existing homes. Some governments have recognized this; British Columbia, for example, has a helpful property transfer tax exemption for newly built homes.

The distinction between new and existing also matters for policy initiatives designed to influence the allocation of homes.

Allocating the existing supply vs. making it harder to build new homes

Given the pre-existing housing shortage, it is no surprise that the general public and policymakers are concerned about non-primary owners buying up existing ownership-based homes. Those concerns are legitimate, noting that these purchases are often a natural market reaction to changing conditions, such as the conversion of existing homes to student rentals in response to a massive increase in international student enrollments.

One area of particular concern has been the role of foreign buyers in the Canadian market, and how their purchases are lowering the supply of available homes for Canadians. This led the federal government to institute a foreign buyer ban to protect the existing housing stock. However, because the ban does not differentiate between buying up existing homes and financing the construction of new homes, it is likely leading to a reduction in overall supply, as an important source of pre-construction condo financing has been blocked.

This is a fixable problem. Australia recognized that buying up existing homes and providing financing for new homes are two substantially different activities, with differing impacts on the housing supply. As such, their foreign buyer ban exempts new or near-new purchases by foreign buyers to help increase the amount of capital available to builders. Canada should institute a similar provision to help increase the housing supply.

It is one thing for governments to influence who can buy existing homes; those policies can have merit, noting that their use has a long and highly problematic history; leading organizations like the CMHC to atone and apologize for past actions. But regardless of their merit when applied to existing homes, when those policies are applied to new homes, they slow the growth of the housing supply, exactly the opposite of what governments are hoping to achieve.

Summarizing with a helpful 2x2 matrix

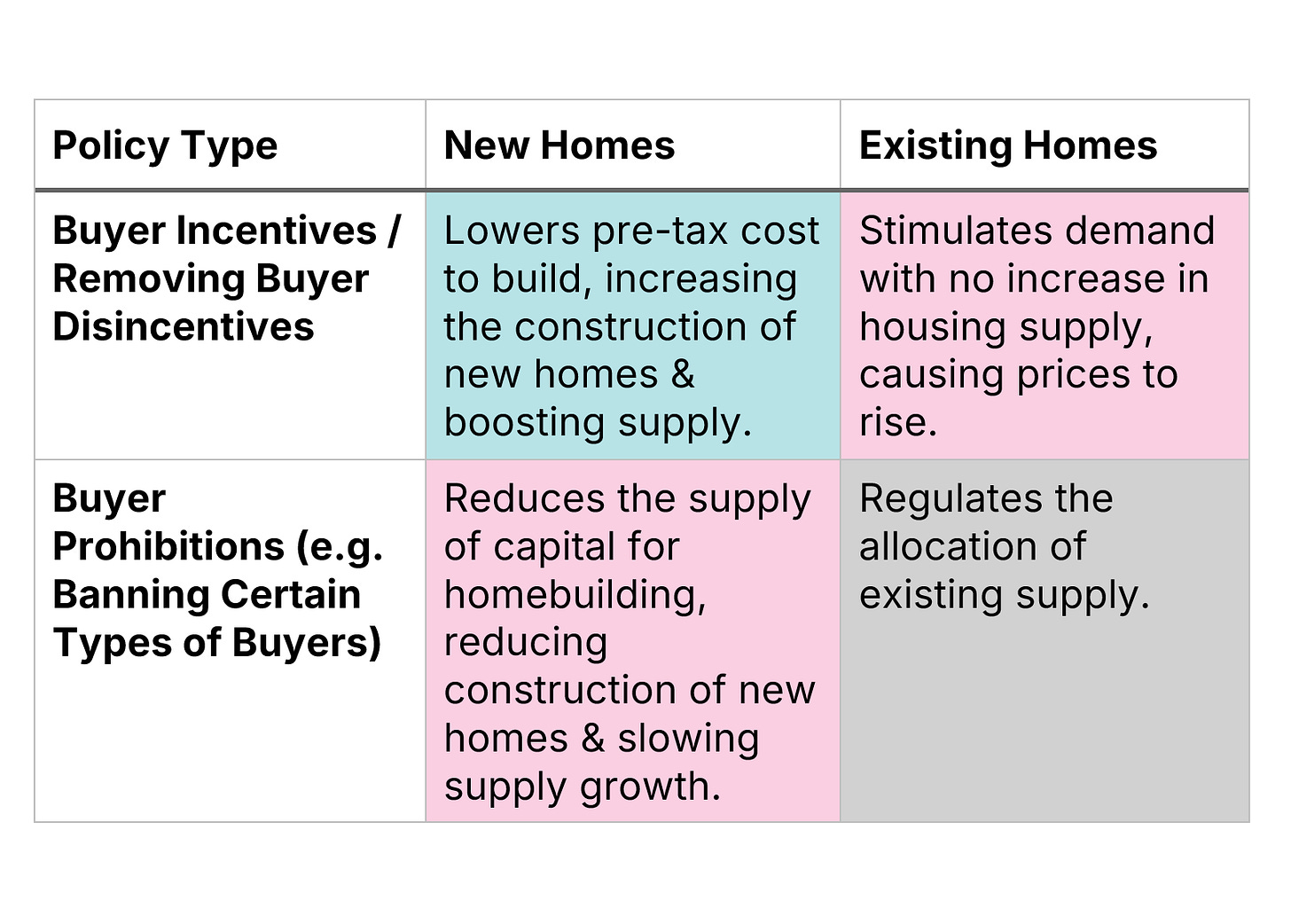

Policies that target new homes vs. ones that target existing homes have substantially different outcomes. In particular, policies that boost demand for existing homes and policies that block capital for new homes have large unintended consequences and are shown in (light) red. On the other hand, policies that look to lower the cost of building new homes have generally favourable outcomes, and are shown in green. The last box is left grey, as policies that prohibit the buying (or renting) of existing properties can be used for both good and ill.

Governments across Canada have set housing supply targets, as they recognize that we need more homes. We can debate whether the targets are the right size, whether the targets should recognize that studio apartments and 3-bedroom homes are not the same, and how population growth should be incorporated into target setting. But there is a nearly unanimous consensus in Canada that housing starts must rise. However, we will not get there unless our suite of housing policies differentiates between new and existing homes.