Surety Bonds Could Unleash Billions Toward Canada’s $2 Trillion Housing Need

Why tying up capital is a luxury we can’t afford

Highlights

Canada will require approximately $2 trillion in capital over the next five years to achieve its housing ambitions. Unnecessarily encumbering working capital in homebuilding is a luxury the country cannot afford.

Policymakers must identify policies and procedures that unnecessarily encumber homebuilding capital and provide policy corrections, such as instituting direct-to-buyer development charge systems.

One source of capital encumbrance is the use of letters of credit (LoC) by developers as a form of financial security in subdivision agreements or site plan agreements.

Surety bonds, which are a form of insurance contract, provide an alternative to LoCs that do not encumber working capital.

The use of surety bonds in subdivision agreements and site plan agreements was a common practice in Ontario well into the 1980s. In recent years, the use of surety bonds has made a comeback, including in many Ontario and Alberta municipalities.

Ontario’s Housing Affordability Task Force report included requiring “municipalities to provide the option of pay-on-demand surety bonds and letters of credit,” as one of their 55 recommendations.

Because these letters of credit are collateralized, they tie up capital, often on a dollar-for-dollar basis. So, a $10 million letter of credit ties up as much as $10 million in working capital, even though the infrastructure expenditures that the capital will be used for may not be deployed for a significant time.

The Association of Municipalities of Ontario have suggested the decision to accept surety bonds should be left to municipalities.

Given the need to unencumber capital, providing developers with the option to use surety bonds has substantial merit. Federal and provincial governments should develop frameworks to streamline their use and ensure that municipalities do not incur any additional risks or costs beyond those associated with the status quo.

Encumbering capital is a luxury we cannot afford

As a recent report made clear, Canada needs to deploy $2 trillion in capital over the next five years, a 5x increase from current levels, if the country is to achieve its housing ambitions. As we wrote last week, it is vital that governments “must enact a series of reforms that address barriers preventing investment in new housing, rules that unnecessarily encumber housing capital”.

Our piece presented several policy solutions to address these issues, including exempting new homes from foreign-buyer bans, enhancing the HST New Housing Rebate, offering LTT rebates for new homes, and including development charges as a separate line item in the price of a home.

Today, we have another policy to add to the list: shifting from using letters of credit in subdivision and site plan applications, which can unnecessarily encumber housing capital, to using surety bonds.

Let’s walk through how this would work, using a development in Ontario as an example.

From site plan to sewer line

Let’s say you’re a developer and you have a piece of land in Ontario that you want to build some housing on. There are a series of approvals you will need from the local municipality, including a subdivision or site plan, with the latter being “a drawing developers and planners use to designate existing and proposed changes to a parcel of land they tend to develop. These site plans will typically show the key elements of the development plan, including buildings, roads, parking, sewer and drainage, water lines, and other essential components.”

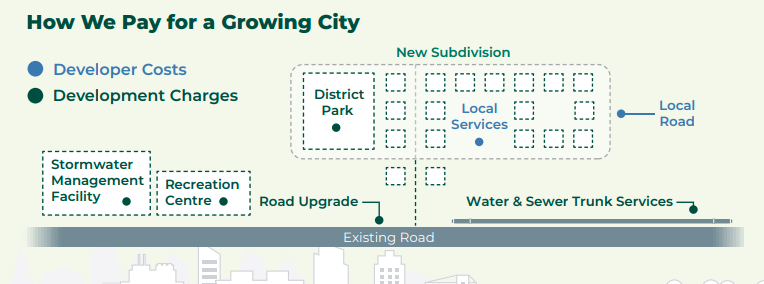

There is a common misconception that development charges pay for all new housing-related infrastructure. However, much of the infrastructure described above is built and paid for by the developer, separate from development charges. The developer pays for and constructs this infrastructure, which is noted as “developer costs” in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Developer Costs vs. Development Charges

Source: City of London.

After a maintenance period, the ownership of this infrastructure will be transferred over to the municipality. This creates an obvious risk for the municipality, as some of the infrastructure may be built late, of substandard quality, or not completed at all, thereby creating a financial liability for the municipality.

Cities need to be financially insulated from these potential negative outcomes. For the past few decades in Canada, municipalities have typically required developers to provide this security in the form of a letter of credit.

Placing funds in a lockbox

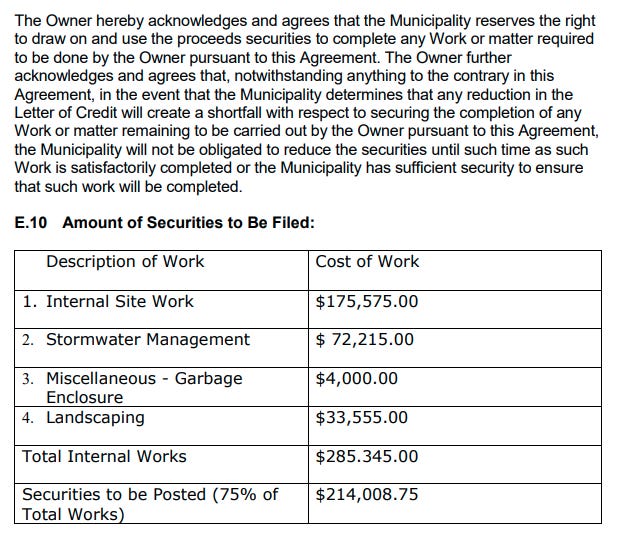

An agreement between a municipality and a developer typically includes a clause similar to Figure 2, which is taken from a consolidated development and site plan agreement between a developer and the Township of Clearview.

Figure 2: Example Site Plan Agreement Clause

Source: Township of Clearview.

The clause identifies a set of infrastructure to be built and improvements to be made to the site, which will be paid for by the developer. The two sides have agreed that the work will cost roughly $285,000. As part of the agreement, the developer will provide a Letter of Credit to the municipality, equivalent to 75% of the estimated infrastructure cost, totalling $215,000. This is a standard agreement clause, although the 75% requirement is not uniform and can be as high as 100% in some cases.

The developer will need to obtain this Letter of Credit (LoC) from a financial institution. Municipalities may differ in their acceptance of letters from specific institutions; for example, Brampton will automatically accept Letters of Credit (LoCs) from the Big Six banks, with LoCs from other financial institutions needing to meet certain requirements and requiring approval from the City’s Treasurer or Deputy-Treasurer. Often, municipalities require specific text in the Letter of Credit that spells out the rights and obligations of each of the parties, as seen in this example from the City of Vaughan.

While the project is underway, the LoC locks these funds to ensure payment can be made if necessary. As noted in the Clearview agreement, the municipality can “draw on and use the proceeds securities to complete any Work or matter required to be done by the Owner pursuant to the Agreement”. In other words, if the developer fails to complete all the infrastructure on time to the required quality, the municipality can use the funds to finish the work itself. When the municipality is sufficiently satisfied that the work is complete, these funds can be released and made available to the developer.

While this system does protect municipalities, it has the downside of encumbering substantial amounts of development capital that can be used for other purposes. And, as we have recognized, unnecessarily encumbering housing capital is a luxury Canada can no longer afford.

Fortunately, there is a solution: surety bonds.

Surety bonds provide a solution, albeit a more complex one

A surety bond, at its core, is a form of insurance. As described by KASE Insurance, it is a three-party contract, involving a principal (the developer), an obligee (the municipality), and a surety (the insurer):

Surety bonds are a legally-binding agreement that involves three parties:

The principal: The party that purchases the bond as a guarantee that they’ll finish the project or task set by the obligee

The obligee: The party that requires the principal to obtain a surety bond

The surety: The party that guarantees the work of the principal to the obligee and assumes the obligation if the principal cannot

Simply put, these bonds act as a promise made by the principal, through its surety company, that a contract will be carried out legally and in accordance with industry standards.

Unlike Letters of Credit, surety bonds do not encumber capital; however, the developer must pay premiums to the insurer. Because, unlike LoCs, surety bonds do not encumber capital, the Ontario Home Builders’ Association (OHBA) has long advocated for changes to the provincial Planning Act that “would permit the use of performance bonds in all development applications in Ontario, at the option of the owner of the land.” Ontario’s Housing Affordability Task Force report echoed this call and included requiring “municipalities to provide the option of pay-on-demand surety bonds and letters of credit,” as one of their 55 recommendations.

Some municipalities across Canada currently permit the use of surety bonds in certain circumstances. In Ontario, these include Innisfil, Niagara Falls, London, Durham Region, Sault Ste. Marie, Pickering, Bracebridge, among many others. More are likely to join, as in November 2024, the provincial government enacted Regulation 461/24 under the Planning Act, providing a framework for their use. Outside of Ontario, municipalities from Calgary to Windsor, Nova Scotia, allow for their use, but municipal adoption tends to be the exception rather than the norm.

Even with Regulation 461/24, surety bonds are not currently offered as an option in most Ontario municipalities. Both the OHBA’s briefing report and the provincial Task Force report note that surety bonds were the norm until the 1980s, when requiring LoCs became more common. Which raises the obvious question, “If surety bonds are superior to LoCs, why don’t municipalities allow the option?”

The challenges to surety bonds can be overcome

Most traditional objections to surety bonds can be overcome through how the bonds are structured. For example, unlike Letters of Credit, traditional surety bonds are not “pay-on-demand”, so there is a risk that the municipality may not be able to receive their money right away, or may have an insurer refuse to pay. However, as noted by an OHBA case study, this can be addressed through a clause in the bond that states that “[the] obligation to pay is on demand, without regard to the equities between the parties and the payout is in cash up to the aggregate amount of the bond”. In other words, surety bonds can be structured as a “pay on demand” instrument, similar to a LoC.

The biggest concern municipalities have is the financial security of the surety bond issuer. In response to the Task Force report, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario, which represents the vast majority of municipalities in Ontario, suggested municipal adoption of surety bonds should remain voluntary, stating:

The Bill establishes regulation-making authority to authorize landowners and applications to stipulate the type of surety bonds and other prescribed instruments to be used to secure obligations in connection with land use planning approvals. While this may help increase certainty in the process, the use of surety bonds should remain an optional tool rather than a mandatory measure.

The financial risk associated with accepting a different instrument of financial security rests with the municipality and ultimately, the local property taxpayer. Thus, the decision to accept the appropriateness of an instrument should remain a local decision, informed by all available evidence. AMO would encourage the surety industry to engage with municipal treasurers, lawyers, and administrators to see if surety bond acceptance merits broader local use.

The Ontario Home Builders’ Association’s (OHBA) request for a provincially imposed requirement to accept surety bonds may increase financial risk for municipalities. The commentary of multiple financial rating services and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions should be sought to assess any associated risks for municipalities and assess the fiscal stability of the surety industry to bear such responsibility on behalf of developers.

This is not an unreasonable concern, given that no insurer is likely to be as secure as a Big Six bank, but the Task Force report notes that “surety companies, similar to banks, are regulated by Ontario’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions to ensure they have sufficient funds in place to pay out bond claims.” The fact that issuers are OSFI-regulated entities should provide municipalities with some relief, recognizing that municipalities still have less experience dealing with surety issuers than they do with the big banks.

The challenges of broad-based surety bond acceptance can be overcome, particularly if municipalities receive support.

Other orders of government can help

In a submission to the provincial government, the Municipal Finance Officers’ Association of Ontario (MFOA) simultaneously recognizes the benefits of using surety bonds, as well as the challenges in requiring municipalities to accept surety bonds. The MFOA provided a number of helpful suggestions, including having the province vet surety bond providers on behalf of municipalities:

The Province should publish a list of eligible insurers through a regularly updated bulletin to minimize the costs on the sector of monitoring insurer credit ratings, and the regulation should include provisions for replacing the pay-on-demand surety bond should the insurer become ineligible as per provincial requirements.

Given the need to ensure that housing capital is not unnecessarily encumbered, both the federal government and the provinces need to provide municipalities with the tools they need to accept surety bonds. For example, the federal government could require municipalities to provide the option to use surety bonds as part of the Housing Accelerator Fund, while also providing municipalities with the funds to train their staff on the intricacies of these instruments.

We have the tools to unencumber capital; we need to use them

Surety bonds should be one of the many tools in our toolbox to unlock the $2 trillion in housing needed to achieve our housing ambitions. Municipalities across Canada, particularly in Alberta and Ontario, are increasingly allowing their use in municipal applications. Metro Vancouver has recently proposed expanding the use of pay-on-demand surety bonds for amenity and infrastructure obligations.

While surety bonds, by themselves, will not free up $2 trillion in capital, they can be an important part of getting us closer to that goal.

Download a PDF of this article here: