Canada Needs $2 Trillion to Build Housing. Here are Four Ways to Unlock It.

We need to attract capital, not block or encumber it.

Highlights

A new report from RBC finds that Canada will need $2 trillion in capital over the next five years to meet its housing ambitions; a fivefold increase from current levels.

Our current policy environment is not well suited to the task.

To achieve that goal, all three orders of government must enact a series of reforms that address barriers preventing investment in new housing, rules that unnecessarily encumber housing capital, and create a policy environment that distinguishes between investment in new homes and purchases of existing ones.

A suite of policies will be needed, which could include exempting new homes from foreign-buyer bans, enhanced HST New Housing Rebates, LTT rebates for new homes, and including development charges as a separate line item on the price of a home.

A trillion here, a trillion there, pretty soon, you're talking real money.

A new report from RBC contains a sobering fact: “[t]ackling Canada’s housing shortage will require $2 trillion in capital deployment over the next 5 years—that’s a 5X increase from current levels.” The federal Liberal housing platform referred to the need to “catalyze private capital”, an acknowledgement that increased private sector capital is necessary to achieve the government’s lofty housing ambitions.

Unfortunately, our current policy environment, including ideas proposed but not yet implemented by the federal government, is not of the magnitude necessary to achieve this ambition.

The RBC report provides three policy proposals: tax-free municipal bonds for housing and infrastructure, tax credits for affordable housing, and financing infrastructure with municipal bonds. These are all avenues worth exploring.

We would add four additional ideas to their list: Exempting new homes from foreign-buyer bans, enhanced HST New Housing Rebates, LTT rebates for new homes, and including development charges as a separate line item on the price of a home.

These suggestions are not “policy for policy's sake” but rather stem from our diagnosis of the barriers to attracting capital.

To solve a problem, you must understand it

The RBC report’s framing leads to the inevitable question, “What are the barriers preventing Canada from deploying $2 trillion in housing capital over the next 5 years?” There are an immeasurable number of possible answers to that question, but three interconnected barriers that come immediately to mind:

Barriers that prevent investment in new housing.

Rules that unnecessarily encumber housing capital, rather than deploying it to productive uses.

A policy environment that does not distinguish between investment in new homes and purchases of existing ones.

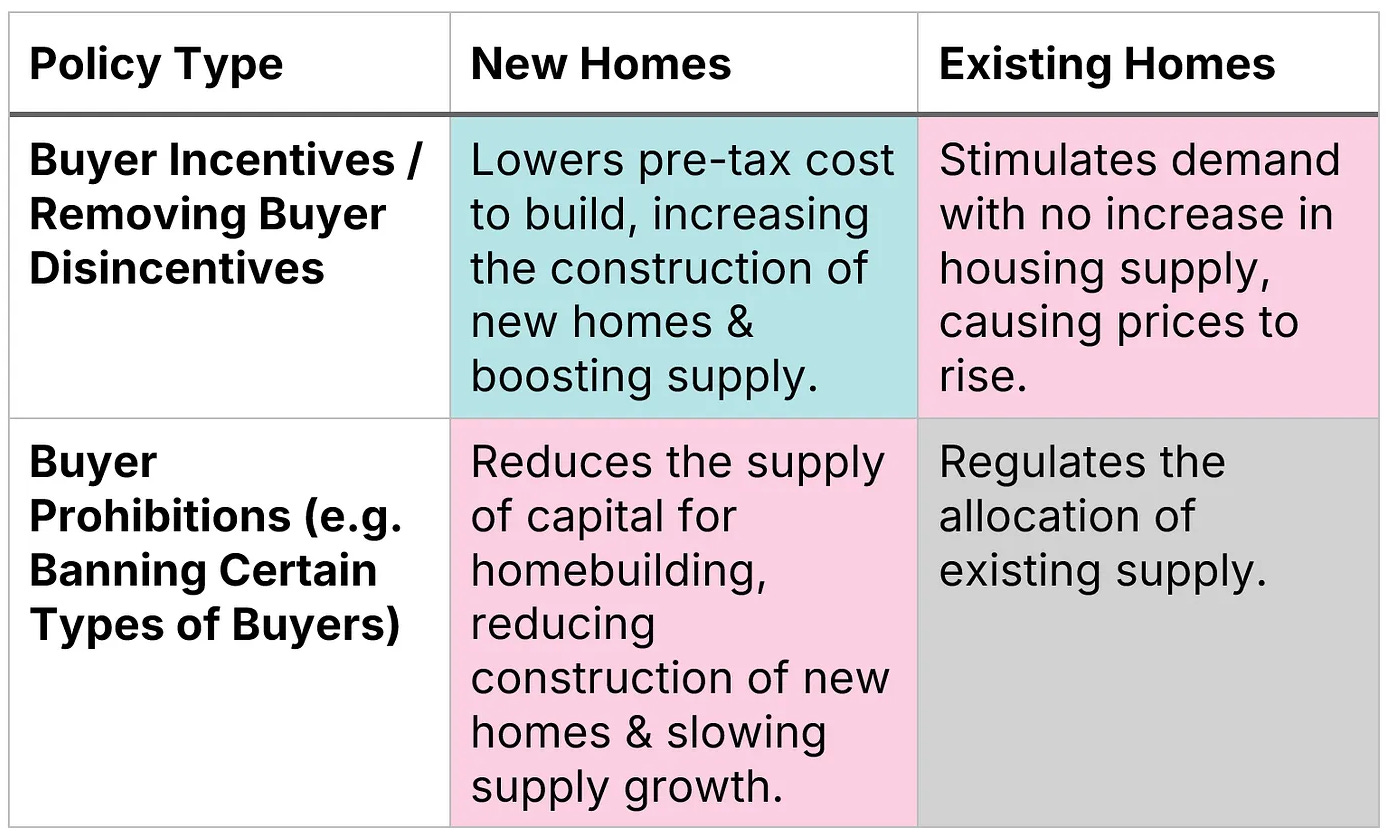

The final barrier is particularly important and is the basis of our piece, “New Homes are the Solution: Policy Must Treat Them Differently”, which illustrates the differing effect that policies can have when placed on new housing construction vs. existing homes.

Figure 1: Impact of housing policies on new vs. existing homes

Source: New Homes are the Solution: Policy Must Treat Them Differently

These three barriers can be addressed through smart public policy; in fact, many policy proposals can simultaneously address two or more of them. Here are four policy ideas which address one or more of these barriers.

1. Exempting foreign investment in new housing from foreign-buyer bans

Canada has a foreign-buyer ban on housing to prevent “foreign commercial enterprises and people who are not Canadian citizens or permanent residents” from buying up existing homes. However, because the ban is applied to all homes, it effectively blocks foreign investment in pre-construction projects, which limits the amount of capital available for housing construction.

Our cousins in Australia have recognized the unintended consequences of a broad-based foreign-buyer ban, and have an exemption that allows foreign buyers to purchase a “new or near-new dwelling”. The Australian model prevents non-residents from buying up existing dwellings while simultaneously giving developers access to the pre-construction capital they need to move projects forward.

In short, the Australian foreign buyer ban acknowledges that policies have differing impacts on existing homes versus new homes and treats them accordingly. Our federal government should consider doing the same.

It is essential to note that this is not the only barrier to investment in housing construction; a multitude of others exist, such as EIFEL rules. Governments should examine their entire suite of policies and redesign ones that are having a negative impact on attracting capital into housing construction.

2 and 3. GST/HST and land transfer tax rebates for new homes

Enhancing the existing GST/HST New Housing Rebate is something we have written about at length (see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). The short version of why a revised rebate is needed is that the GST only applies to new housing, so it acts as a development tax (or, if you prefer, a development charge), increasing the cost of homebuilding and causing fewer homes to be built.

By enhancing the existing rebate, which hasn’t been updated for inflation since it went into effect on January 1, 1991, the post-tax price of new home construction falls by as much as 5%. And, in Ontario, coupling this with a revised provincial rebate would reduce post-tax new home prices by nearly 13%. Premier Ford has repeatedly indicated his willingness to introduce a revised provincial rebate should the federal government do the same.

What has received less attention from us is the land transfer tax (LTT). Homes sold in the City of Toronto are subject to a provincial Land Transfer Tax (LTT) and a municipal LTT, which, when combined, can be as high as 4% of the home's value.

One question we’re often asked at the Missing Middle is, “Why don’t seniors downsize and move into a new, smaller home, freeing up their larger house to the next generation of families?” There are many answers to this question, but tax is one of the biggest ones. Between GST, PST, and LTT alone, Toronto seniors must pay a combined tax of nearly 17% on a new home, and that does not include other closing costs and fees, embedded taxes such as development charges, nor does it include the nearly 4% that the buyers of their home also have to pay in combined provincial and municipal land transfer taxes.

In short, if policymakers want seniors to be able to downsize as they age, we cannot impose punitive levels of taxes on them for doing so. A revised provincial/federal HST rebate would go a long way. Similarly, introducing LTT rebates on new homes in Toronto and Ontario, as is currently done in British Columbia, would also be beneficial. British Columbia recognizes that LTTs have differing effects on new homes versus existing ones, and smartly provided a full rebate for new homes (under a certain value). Ontario should do the same.

With these rebates, the cost of construction would be significantly lower, and capital would be attracted to the sector from various sources, including families who wish to downsize into a seniors-friendly condo and are willing to provide pre-construction deposits and wait a few years for the building to be completed.

To be clear, the goal with these rebates is not to favour one group over another, nor is it to provide subsidies to seniors; rather, it is to lower the transaction costs that contribute to lower housing supply and lead families to stay in housing that is not best suited to their needs.

4. Development charges as a separate line item

We examined this idea in depth in the piece British Columbia Can Substantially Lower Housing Costs with One Simple Trick. In one Vancouver condo case study, municipal development charges and related fees totalled $130,000 per unit, amounting to $10,000,000 for a 75-unit project. The developer pays this money when they receive their building permit, using borrowed money. They finance this cost over 18-36 months, then pass those costs along to the end buyer, with interest and other “junk fees”. Because the development charges and interest on those charges are embedded in the final price of the home, they are subject to GST and property transfer taxes, resulting in a tax-on-tax situation. The interest costs, other miscellaneous fees, and tax-on-tax increase the development charge-related expenses to the buyer to nearly $180,000 per home, with much of that increase being pure waste.

While the junk fees and increased costs are problematic enough, the current model also requires the developer to borrow over $10 million on the project to cover development charges and interest costs. This unnecessarily encumbers a significant amount of working capital that could be put to more productive use. When Canada needs $2 trillion in capital over five years, we cannot afford to tie up even one dime worth of capital unnecessarily.

Under the development charge (DC) system on ownership housing, the developer is acting as a flow-through entity, with the government charging the developer DCs, then the developer passing along those costs (plus interest and other junk fees) to the end buyer. This is unnecessary. Instead, we could eliminate the middleman and have municipalities charge DCs directly to the end homebuyer, as they do with any other tax. This would eliminate those interest costs and junk fees, and also end DC tax-on-tax, as the development charges would be a separate line item, except from GST and property transfer taxes. In our case study, this reduced the final price for the homebuyer by over $68,000, while at the same time not depriving municipalities of a single cent of DCs.

If a $68,000 saving for homebuyers was not beneficial enough, this model also eliminates the need for developers to borrow to cover development charges, freeing up capital that could be put to more productive uses, such as building more housing.

Unnecessarily encumbering working capital in homebuilding is a luxury that Canada cannot afford. This development charge scenario is just one example of how capital is unnecessarily encumbered in our current system, but there are others. All three orders of government should audit their suite of housing policies to find ways to reduce the amount of unnecessarily encumbered capital in homebuilding.

Two trillion is a big number which can only be achieved through substantive reforms

A 5x increase in working capital is a big, hairy, audacious goal, and skeptics would be forgiven for thinking it is unachievable. Making that vision a reality requires all three orders of government to enact a series of reforms that address barriers preventing investment in new housing, rules that unnecessarily encumber housing capital, and create a policy environment that distinguishes between investment in new homes and purchases of existing ones. The four reforms in this piece meet those requirements, but many more will be needed.