Lowering Development Charges Would Not Bankrupt Governments

DC rates are high because costs are imposed on a relatively small number of people

Highlights

High development charges in Ontario have contributed to the exclusion of an entire generation of young middle-class families from owning a home.

Although development charge rates are high, only $2.4 billion in development charge revenue is spent in the average year.

The province of Ontario, along with federal political parties, has signalled a desire to work with municipalities to reduce development charges and other municipal housing construction taxes.

Relative to provincial and federal budgets, replacing some or all of development charge spending is manageable, particularly if the revenue comes from multiple sources.

Governments could fund these expenditures out of general revenue, but that is only one option of many.

There are many fairer, less expensive, and more direct revenue streams than development charges. For example, water infrastructure can be paid for by creating municipal service corporations. Roads can be paid for through gas taxes, new car registrations, and license plate renewals, and parking garages can be paid for from revenue from parking fees.

Further development charge cuts may be coming to Ontario

Over the last year, three Ontario municipalities have lowered development charges: Burlington, Vaughan, and Mississauga. This week, Ontario’s government, through the speech from the throne, signalled a desire to work with municipalities to achieve further and more widespread development charge reductions:

Following the example of leaders like Mayor Steven Del Duca of Vaughan and Mayor Carolyn Parrish of Mississauga, the province will leverage these growing investments to work with municipalities to lower their costly local development fees that add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of a new home for Ontario families.

A common argument against development charge reductions is that they generate too much revenue and are too big to replace. While it is true that development charge rates are sky-high, overall revenues and expenditures from development charges (DCs) could be replaced in any number of manageable ways. By spreading the infrastructure costs over a larger tax base, we can find fairer, less expensive, and less distortionary ways of funding the infrastructure that Ontario needs.

How we fund infrastructure is a choice. Nothing forces municipalities to use DCs, and likewise, nothing requires the province to allow municipalities to use DCs to fund infrastructure, let alone other priorities that have nothing to do with housing-related growth, like municipal cemeteries, safe injection sites, and state-of-the-art soccer facilities.

The choice to use development charges, which have reached nearly $200,000 a home in some municipalities, has contributed to pricing out an entire generation of young middle-class families from owning a home. All because governments chose to place the annual burden of these expenditures onto less than 1% of the population.

Finding the revenue to lower, if not replace, development charge revenues is a manageable problem.

A total replacement of development charge expenditures would cost around $2.4 billion a year

There are two different ways to quantify the overall size of annual development charges: how much is raised by development charges (revenue), and how much development charge revenue is spent each year (expenditures).

Between 2018 and 2022, the last five years with complete municipal data, cities in Ontario received an average of $3.5 billion each year in revenue, but spent only $2.4 billion.

In theory, development charge revenues should equal development charge expenses over long periods. However, this is rarely the case in practice; for example, the city of Toronto has had development charge revenues exceed expenditures in 13 of the last 14 years, causing its development charge reserve fund to grow to over $3 billion.

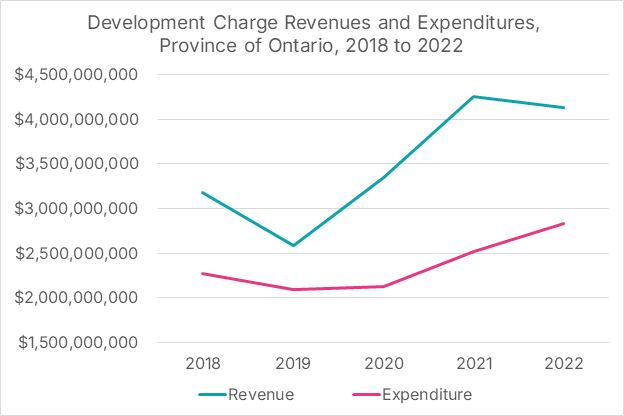

One obvious way to reduce development charge rates is to set them at rates where revenues meet expenditures. Instead, as shown in Figure 1, municipalities collect a billion dollars more each year in development charge revenue than they spend. This has created a pool of dead money in the form of cash hoards sitting on the books of many municipalities.

Ultimately, development charge expenditures provide a better indication of the cost of lowering or replacing development charge rates since using DCs to build cash hoards is an entirely inappropriate use of public funds.

Figure 1: Development Charge Revenues and Expenditures, Province of Ontario, 2018 to 2022

Figure 1 also illustrates one of the other large problems with development charges: They are not a stable source of funding. Because homebuilding, particularly at the individual municipal level, is prone to boom-bust cycles, revenues can jump suddenly just as easily as they can collapse, both of which we saw in the last five years. Using DCs to finance infrastructure creates precarity, which is a choice to do over providing more stable and consistent sources of funding.

Development charge expenditures are relatively small compared to the provincial budget

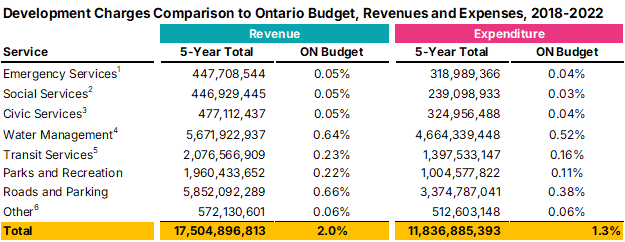

Over the last five years, Ontario municipalities have collected $17.5 billion in development charge revenues, but spent only $11.8 billion. To put these numbers in perspective, we can compare them to the provincial budget. Over the last five years, the province of Ontario has spent $889 billion, for an average of $177.8 per year.

In percentage terms, annual development charge revenues are equivalent to 2% of provincial expenses, and annual DC expenses are equivalent to 1.3% of Ontario’s annual budget. This comparison puts the size of these in context; it is important to note that development charge revenues and expenditures are at the municipal, rather than provincial level. However, given this week’s speech from the throne, where the province has indicated a willingness to work with municipalities to lower development charges, the comparison between development charge outlays and the provincial budget is suddenly quite relevant.

It is important to note that there is not just one development charge; rather, development charges consist of a series of fees for different services. The provincial government has the option of reducing or eliminating some of these individual charges with other sources of revenue.

The list of eligible services is quite long, so we have aggregated development charges into eight different buckets1. As shown by Figure 2, some of these individual categories are incredibly small compared to the overall size of the provincial budget.

Figure 2: Development Charges by Category, Compared to the Provincial Budget

We’re not suggesting that the province should fund every category of service, or even necessarily any single category of service, through general revenue. However, if the government did do this, the financial cost would be manageable, as these costs would be spread over the entire population rather than imposed on a relatively small group of new renters and homebuyers. The status quo, where we impose these costs on a very narrow band of young people trying to buy a home and start a family, is exceptionally harmful to their well-being and society as a whole.

Some categories, however, lend themselves particularly well to being funded out of general revenue. For example, new homes have paid almost $450 million into social services through DCs over the last five years. The social services category includes long-term care homes, affordable housing, daycares, and public health. While these services are necessary, their connection to new housing is nebulous at best. If the province had picked up the tab on them, it would’ve cost an additional 0.03% in extra spending over what they actually spent between 2018 to 2022, a manageable sum.

There are many other ways that the province could fund these services rather than out of general revenue. For example, water and wastewater could be funded through municipal service corporations, a recommendation from Ford’s Housing Affordability Task Force report that has yet to be implemented. Instead of funding new roads through taxes on housing construction, a fairer, more logical approach could be to fund roads through fees on cars, such as gas taxes, new car registrations, and license plate renewals. Parking garages can be funded from the revenues from parking fees, rather than through municipal housing taxes placed on renters and homebuyers who may not even own a car.

In short, there are many ways the province could reduce these fees, creating a fairer, less expensive system without breaking the bank. Paying for them out of general provincial revenue is only one option; future work will examine other alternatives.

Download a PDF version of this article below:

Emergency services (1) includes Police, Fire, EMS, Emergency Preparedness; Social Services (2) includes Long-term Care, Affordable Housing, Daycare, Public Health; Civic Services (3) includes Libraries, General Government, Development Studies, Cemeteries, Bylaw Enforcement, Animal Control; Water Management (4) includes Water, Wastewater, Stormwater; Transit Services (5) includes Transit, GO Transit, Subway Extension; Other (6) includes Electrical Services, Waster Diversion, and Codes 290, 295, 296, 297 in FIR for 'Other'.