Why Lower Construction Costs and Taxes Are the Only Path to More Homes and Lower Prices

The GTA as an alarming case study

Highlights

Home prices have fallen by 20% in the GTA over the past three years, which has helped the region make some progress towards affordability.

However, the sale of newly constructed and pre-construction homes has decreased by over 90% in the GTA in the last three years, encompassing all forms of housing, from high-rise condos to single-family homes.

A Bank of Canada study suggests that a 20% price drop from a demand shock should have led to home sales falling by 20-40%, not 90%.

The oversized reduction can be attributed to an inherent “price floor” for new housing. Once a certain threshold is reached, prices are insufficient to cover the cost of building, and activity stops.

This poses a significant challenge for governments, which aim to achieve both housing affordability and robust growth in housing supply. However, all else being equal, lower prices reduce the viability of building.

The only way to achieve both housing affordability and robust supply growth is through a program of substantial cost reductions.

The most direct lever that governments have to reduce costs is through tax reductions. This can include exempting newly constructed homes from land transfer taxes, reforming development charges, and enhancing the HST New Housing Rebate, which can reduce costs by over 10%.

While tax reforms have a fiscal cost, governments are facing a $6.6 billion reduction in annual tax revenue from the GTA’s housing decline. Both action and inaction have a fiscal cost.

The broken economics of GTA homebuilding

Home prices have fallen by 10% or more over the past three years in Southern Ontario and the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, and by 20% in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), which has improved the affordability of these regions. Unfortunately, housing starts have declined substantially in the GTA, and the sale of new and pre-construction homes has decreased by over 90% in the region.

The combination of falling home prices and falling new home sales is not a coincidence, as, all else being equal, lower home prices reduce the viability of homebuilding. And once prices go too low relative to costs, homebuilding ceases altogether, which is what we are currently seeing in the GTA.

This presents a challenge for governments, which aim to achieve both housing affordability and increased housing supply. The only pathway to achieve both is a substantial reduction in homebuilding costs, and the biggest lever that governments have to lower costs is through a reduction in the GST.

Let’s go back to Economics 101

One of the most basic test questions a first-year economics student is likely to encounter is: “What happens when there is a negative demand shock for a good or service?”

The answer is that both the price and the number of units exchanged fall.

Economics 101 is often a poor model of real-world phenomena, as it excludes various real-world complications, to the extent that we typically discourage its use in our pieces. However, it does a remarkably good job of explaining what has happened to the Greater Toronto Area’s housing market.

Let’s examine the GTA’s housing market from a supply-and-demand perspective. Several factors, most notably rapidly increasing mortgage rates, a weak economy, the migration of families to other cities and provinces, and reduced population growth, have lowered economic demand for housing, resulting in prices falling by over 20% from peak levels.

Figure 1: Greater Toronto Area, Home Prices by Type

Data Source: CREA. Chart Source: MMI

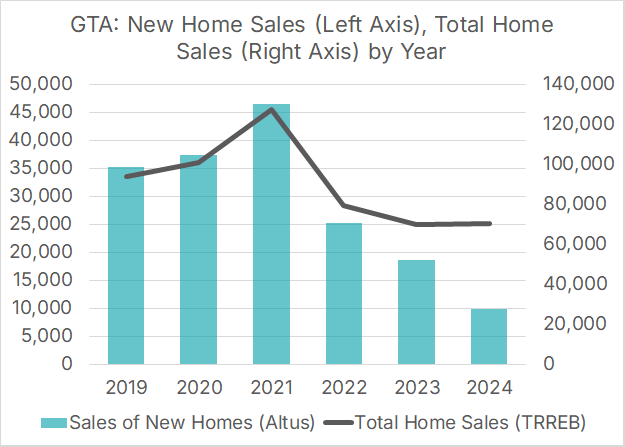

As Economics 101 predicts, a negative demand shock has also led to a decline in home sales. Total home sales (which includes both new homes and resale homes) fell by 44% from 2021 to 2024, while new home sales fell by 80% between those two years.

Figure 2: Greater Toronto Area, New Home Sales (Left Axis) and Total Home Sales (Right Axis) by Year

Data Source: TRREB, BILD. Chart Source: MMI

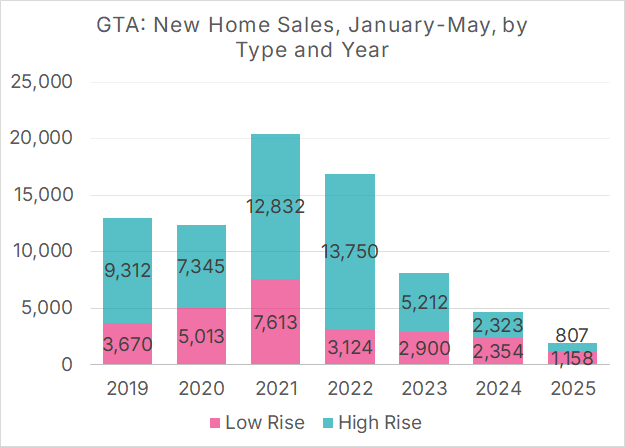

And the outlook for 2025 is even worse. In the first five months of 2025, new home sales were less than half of those in 2024 over the same period.

Figure 3: Greater Toronto Area, New Home Sales, January-May by Year

Data Source: BILD. Chart Source: MMI

Put it together, the sale of new homes is down by over 90% from the 2021 peak and by more than 80% from pre-pandemic levels.

This raises an obvious question: “Why did a drop in demand lead to only a 20% drop in prices but over a 90% drop in new sales?”

The answer to that question reveals the challenges that governments will have in achieving their housing supply targets.

Historically, supply has not been this sensitive to prices

Economists have a concept known as “price elasticity,” which measures how responsive demand (or supply) is to a change in price, all else being equal. In practice, these can be challenging to estimate, particularly for housing construction, as controlling for other factors can be challenging. A September 2021 research note by the Bank of Canada finds that for every 1% increase in home prices, supply should increase by 2.2%. However, this estimate varies substantially by metro region, and for a supply-constrained region such as the GTA, supply should increase by 0.89%.

These measures suggest that a 20% decrease in home prices should lead to an 18% decrease in sales (using the GTA elasticity estimate). Even if we’re generous and apply the Canada-wide elasticity estimate, that only translates into a 44% drop in sales, which is approximately the decline in resales, but nowhere near the 90% decline in new sales.

Three additional factors have caused new home sales to drop by 90%, rather than by 20-40%:

The cost of homebuilding has risen since 2021, so not all else has been equal. Higher interest rates not only impact the (economic) demand for housing, but they also impact supply, as builders and developers must pay higher rates on their construction loans. Development charges in the GTA have increased since the 2021 supply peak, and so have material costs.

Falling prices deter investment in pre-construction properties. Mom-and-pop investors will not want to invest in an asset they believe will be worth less in the future than it is today. These investors have historically been a crucial source of pre-construction sales and capital for the condo market.

New housing construction has an inherent price floor.

The third factor is worth a detailed examination.

The price floor of new housing: Homebuilding stops when prices approach costs

Elasticity estimates, derived from past data, are often poor predictors of behaviour during large demand-driven price drops. When overall market prices increase or decrease by a relatively small amount, builders and developers will adjust their plans accordingly, by making adjustments to their own prices and product offerings. However, when prices fall a lot, they reach a point where the price is not adequate to cover the total cost of construction (including land). This applies equally to not-for-profit and for-profit builders, as for-profit builders will only be able to obtain financing from the CMHC or financial institutions if the project has a sufficient profit margin. Otherwise, the loan is too risky to take on.

Of course, costs are not a constant, and there are measures that builders and developers can take to reduce these costs. They can build smaller homes with lower quality finishes and, where possible, on smaller plots of land. While this does reduce the cost of the home, it also reduces the quality, and new homes must compete with resale homes on the market. Selling a lower-quality product and a reduced price point can be helpful, but it is not a panacea.

Over time, some costs will naturally decrease due to the slow growth in the homebuilding industry. Land costs will decrease due to a lack of demand, and labour costs will also decrease as workers have fewer projects competing for their labour. This process can take time; however, having large numbers of out-of-work and underemployed (and underpaid) workers is hardly a beneficial thing for an economy.

There is only one pathway to middle-class housing affordability and high supply growth: Lower costs

The GTA is a case study on the biggest challenge that governments must face when addressing the housing crisis. They are simultaneously trying to accomplish two things that, on the surface, appear contradictory. Specifically, governments wish to:

Make housing attainable for the middle class. We should be very clear about this: in the GTA, there is no pathway to middle-class housing affordability without a decrease in prices.

Increase housing starts. Both the federal government and the province of Ontario have set a goal to double the number of housing starts.

But as we’ve seen in the case of the GTA, substantially falling housing prices (#1) eliminate any economic incentive to build any housing, let alone more housing (#2).

The only way to make the math work at all and achieve lower prices and robust homebuilding is to have costs fall further and faster than prices. A 20% drop in prices requires a 20% drop in costs for margins to remain unchanged and for the economics of building to be roughly equivalent to what they were at higher prices.

In one sense, the market will take care of this. The price of some inputs, such as land and labour, will fall. After a while, increased homebuilding will occur, and as economic conditions improve, homebuilding will accelerate, causing land and labour to become more scarce. As a result, both home prices and input costs are expected to rise. So we get more of (#2), but at a cost of (#1).

Instead, governments must find ways to cut costs. The most direct way they can do so is by cutting taxes on new home construction. For example, British Columbia does not charge land-transfer taxes on some newly constructed homes, a model that other provinces can follow. Development charges often add up to over $100,000 a home in Ontario and British Columbia. These costs can be reduced, often at a low or no cost to municipal governments, by charging them at occupancy and exempting them from the GST and land-transfer taxes.

The fastest and most immediate way to reduce costs is through offering the First-Time Homebuyers’ GST Rebate to all purchasers of primary residences. A combined federal-provincial rebate can immediately reduce the cost of a new home in Ontario by over 10%, a substantial savings. While this comes at a fiscal cost ($1.6 billion annually to the federal government and $895 million to the province of Ontario), the decline in housing starts in the GTA will cost all three levels of government a combined $6.6 billion per year. Both action and inaction have a fiscal cost.

Of course, there is a real risk here that rising land costs would eventually absorb these savings, leading to a continued lack of affordability. This can be prevented through a combination of more sensible and flexible land use planning that incorporates accurate population growth projections, streamlining municipal approvals processes, along with as-of-right building of “missing-middle” housing, and making it possible to build European-style small apartments through reforms to the building code.

Governments need a middle-class housing plan that addresses the cost of building

Without substantial cost reductions, we cannot achieve both an increase in housing supply and improved housing affordability, as lower home prices without corresponding cost reductions reduce the viability of building. And until our governments recognize that and introduce bold plans to cut those costs, housing will remain in crisis in Canada.

Download a PDF of this article here: