Higher Home Prices or Lower Homebuilding Costs: The Choice Governments Can’t Avoid

How policy choices determine whether "q" rises through prices or costs

Highlights

Tobin’s q explains the slowdown in new home sales better than any headline. When the market price of existing homes is below the minimum profitable cost of building new ones (q < 1), construction doesn’t pencil out, and housing starts eventually crash.

Markets will push q back to 1, but the path matters. Convergence can happen through higher prices or lower costs. Given Canada’s affordability crisis, letting prices do the work would be disastrous. Governments can and must step in to lower homebuilding costs.

Governments have far more cost levers than is commonly acknowledged. From zoning and approvals to financing, taxes, construction timelines, and development-charge design, at least ten policy pathways can materially lower replacement costs.

The real choice is affordability now or price spikes later. If governments act to reduce costs below resale prices, we can unlock new supply without reigniting runaway home prices. Failing to do so will create the conditions for the next great price spike.

Q has the Answers

We are living through an apparent paradox: the very reduction we need in home prices is preventing the homes we need to be built. But unlike many paradoxes, this one has a solution.

In a recent piece at Maclean’s titled The Condo Crash is Spreading, I note that the view that Canada’s homebuilding decline is simply a Toronto and Vancouver condo crash is incorrect: we’re seeing declines in other housing forms and in other markets, such as new single-family home sales in Kitchener-Waterloo.

The reason for the decline is straightforward: Home prices, including resale home prices, have fallen. This is a painful adjustment, but ultimately, however, necessary to achieve affordability. However, construction costs have remained the same or risen, creating conditions in which the price to buy an existing home is lower than the “replacement cost” of building an equivalent new home.

In other words, if the cost of building a new home (of a particular type in a particular location) is $1.1 million, and the price of an equivalent resale home is $950,000, then those new homes will not be built. Buyers will opt for the less expensive option.

This rather obvious insight is formalized in an economic concept called Tobin’s q. For housing, Tobin’s q can be written as follows:

Housing Tobin’s q = Market price of existing homes / minimum profitable production cost

When Tobin’s q is less than 1, new home sales and investment slow down considerably, the exact condition that describes many of our housing markets across Canada.

Returning q to 1 and a choice for governments: higher home prices, or lower costs?

The condition where market prices are below replacement cost will not persist forever. Eventually, the two will converge, and q will rise back up to 1. This convergence will happen through some combination of cost reductions, such as the price of labour and land reducing due to reduced demand, and the prices of existing homes rising, as a period of slow home building makes housing relatively scarce, leading to eventual price appreciation.

Given that Canada continues to have a middle-class affordability and housing crisis, convergence through home price increases would be disastrous. While markets will put downward pressure on some costs, governments can and should play a role in driving costs down to, or below, the minimum profitable production cost (also known as the replacement cost of building a home).

A conception of costs

When it comes to homebuilding costs, developers and financial institutions think in terms of pro forma documents. Economists, however, will tend to think in terms of equations. The cost function of building a new home in Canada can be modelled as follows:

c = (p + h + l + f)(1+i)ʸ(1+v)(1+τ)

where

c = “replacement” cost of building a home

p = pre-construction costs, such as the costs of rezoning, conducting studies, etc.

h = hard construction costs (materials, labour, etc.)

l = per-unit cost of land

f = government fees (development charges, community amenity charges, etc.)

i = annual interest rate on a construction loan

y = length of time for construction (in years)

v = minimum viable profit margin

τ = sales tax rate (including GST, land transfer taxes, etc.)

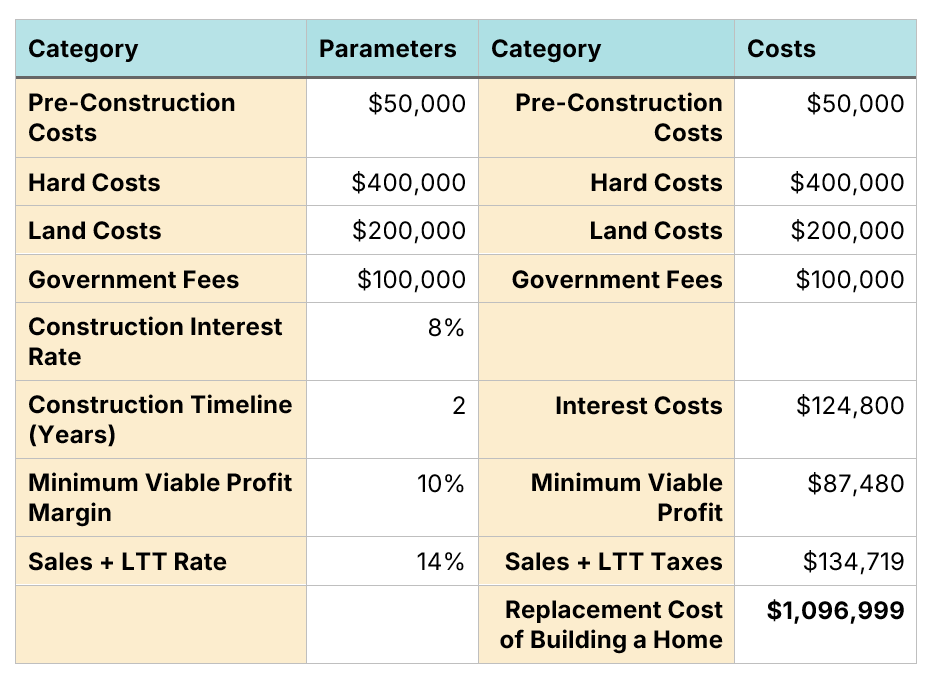

Like all equations in economics, our cost equation is an approximation of reality, but it provides a useful tool for analysis. The relationship between the inputs becomes more tangible when we plug in some numbers. Figure 1 illustrates the per-unit cost for a hypothetical project.

Figure 1: Example of the cost of building a new home

Source: MMI.

These are strictly hypothetical values; the actual value on any project will differ substantially from Figure 1. The “minimum viable profit margin” here is particularly low; in the vast majority of cases, even a seasoned builder would need a margin of at least 12% before a financial institution would even consider lending on the project, with 15% being considered more typical. For a less experienced builder, 18% or more might be required. But these are just hypothetical values.

To prevent future home prices from spiking, governments should look to reduce these costs at least to the level of resale homes. Our replacement cost formula identifies at least ten pathways for governments to lower homebuilding costs. We will use our hypothetical home to illustrate the potential savings from these pathways.

Ten Pathways to Lower Homebuilding Costs

Pathway 1: Lower pre-construction costs. Governments can streamline approval processes, allow for more as-of-right building, and eliminate unnecessary studies, among other reforms. In our hypothetical example, a $1 reduction in these costs leads to a $1.43 reduction in the overall cost of building a home, as it also reduces the amount of interest payable, the minimal viable profit margin (in dollars), and the sales tax payable. This $1 reduction in cost leads to a $1.46 savings relationship also holds for pathways 2, 3, and 4.

Pathway 2: Lower hard construction costs. There are many ways governments can do this; innovation policy and building code reform play a role.

Pathway 3: Lower land costs. Opening up additional land for development is one way, but it is not the only way. Reducing height restrictions and enacting zoning and building code reform can allow for more efficient land use, allowing builders to get more out of a single piece of land.

Pathway 4: Lower government fees. MMI has written dozens of pieces on the need to lower development charges and other costs. Some municipalities, from the City of Vaughan to the City of Vancouver, have done so, and the 2025 federal budget allocated billions to development charge reduction.

Pathway 5: Lower the interest rate on construction loans. This does not require interfering with monetary policy. The federal government can offer lower-rate loans for construction, as the CMHC does through the ACLP program. Regulatory reforms that reduce construction risk, or increase lending options for construction financing will also lead to lower market rates for housing construction. Reducing the interest rate on a construction loan from 8% to 7% reduces per-unit costs by just over $20,000, assuming no other changes.

Pathway 6: Reduce construction duration. Simplifying the building code, and accelerating modern methods of construction can increase the length of time it takes to build a home, whether it’s a single-family home or a high-rise tower. Taking 23 months rather than 24 months to finish the unit reduces the loan duration and overall costs by just under $7,000, assuming no other costs change. In reality, accelerated construction would almost certainly reduce the hard construction costs.

Pathway 7: Lower the minimum viable profit margin. As with construction loans, de-risking projects, or changing the criteria for ACLP funding can lower the profit margins needed for financial companies to lend. Reducing this from 10% to 9% lowers the replacement cost by just under $10,000.

Pathway 8: Reduce sales and land-transfer taxes on new homes. A new home built in the City of Toronto is subject to a 5% GST, an 8% PST, an Ontario land-transfer tax (2% for amounts exceeding $400,000 and 2.5% for amounts exceeding $2 million), and a City of Toronto land transfer tax (also 2% for amounts exceeding $400,000, with rates reaching as high as 7.5%). For a $1 million home, the combined marginal rate is 17%, with average rates slightly lower due to rebates and tax bracketing.

A combined federal-provincial HST reduction on new homes could significantly reduce costs. Reducing average tax rates from 14% to 13% reduces the home’s replacement cost by $9,600. Eliminating them entirely saves nearly $135,000.

Pathway 9: Have development charges payable at the end of the project, rather than the beginning. Development charge deferrals have become increasingly popular, as they substantially reduce the cost of homebuilding without cutting development charge rates. By making development charges payable at the end of the project, they do not need to be financed during construction, thereby reducing the loan the builder must obtain.

In this scenario, replacement costs are reduced by nearly $21,000 because construction interest is no longer paid on development charges; there are also minor reductions in the minimum viable profit margin and sales taxes payable. Note that development charges aren’t being reduced by a dime in this pathway; the $21,000 savings come from when the payment is made, not from the size of the payment itself.

Pathway 10: Have development charges payable at the end of the project, rather than the beginning and exempt those charges from sales taxes through a “direct-to-buyer” model. This is known as the direct-to-buyer model of development charges. The benefit to this model is that, instead of burying DCs in with other costs, they are treated as a separate line item on the bill, which allows governments to make development charges exempt from sales and land transfer taxes.

A direct-to-buyer model shaves $46,000 off of this project, as development charges are no longer compounded by construction interest, developer margin, and sales taxes. As with Pathway 9, development charges still exist and have not been reduced by a single dollar, but the overall cost of the project has decreased substantially.

Governments have a choice: affordability today or price spikes tomorrow

When the price of resale homes is lower than the replacement cost of construction, either prices must go up or costs must come down. By focusing on cost reductions, governments can avoid future price spikes that would make an affordability crisis even worse and accelerate the construction of new homes. And governments have plenty of options to make that happen.