Our 2026 Housing Policy Wish List: Ten Ways to Fix the Crisis

Ten reforms that would make it possible to build homes middle-class families can actually afford

Highlights

The housing crisis is still here and will only be fixed through well-designed policy. That’s why we are releasing our 2026 “Housing Policy Wishlist” of ten sets of housing reforms we would like to see enacted in the coming year.

Canada’s housing crisis is a cost-of-delivery crisis. In much of the country, it is simply too expensive, by policy design, to build homes that middle-class families can afford, even before land and profit are considered.

We’re taxing new homes like cigarettes. Development charges, sales taxes, and land-transfer taxes stack up on new housing in ways that punish first-time buyers and renters, inflate construction loans, and slow the very supply we need.

Housing policy ignores families. Treating a studio condo as equivalent to a three-bedroom home has left Canada with a massive shortage of family-sized housing, while zoning, building codes, and fees often make these homes illegal or uneconomic to build.

Broken rules are blocking better homes. Outdated building codes, fragmented zoning, and glacial municipal approvals prevent Canada from building the kinds of family-friendly apartments and “missing-middle” housing that are common in peer countries.

Governments lack a clear housing vision or metrics to judge success. Without explicit goals, performance indicators, or accountability, Canadians have no way to know whether housing policies are actually improving affordability for the middle class.

Can our dreams come true?

The end of the year is always a time for reflection, as well as creating goals, plans, and wishes for the New Year. As we are still in the midst of a middle-class housing crisis, we have created a ten-point Housing Policy Wishlist. This wishlist focuses on addressing the cost-of-delivery crisis that makes it impossible, in many parts of Canada, to create suitable homes that middle-class families can actually afford.

Before the end of the month, we will have a wish list of non-housing policies to help the middle class.

Given MMI’s mandate to improve the living conditions for middle-class Canadians, our wish list focuses on market-rate housing. Needless to say, we hope our friends in the social housing and ending homelessness spaces have their wishes answered as well.

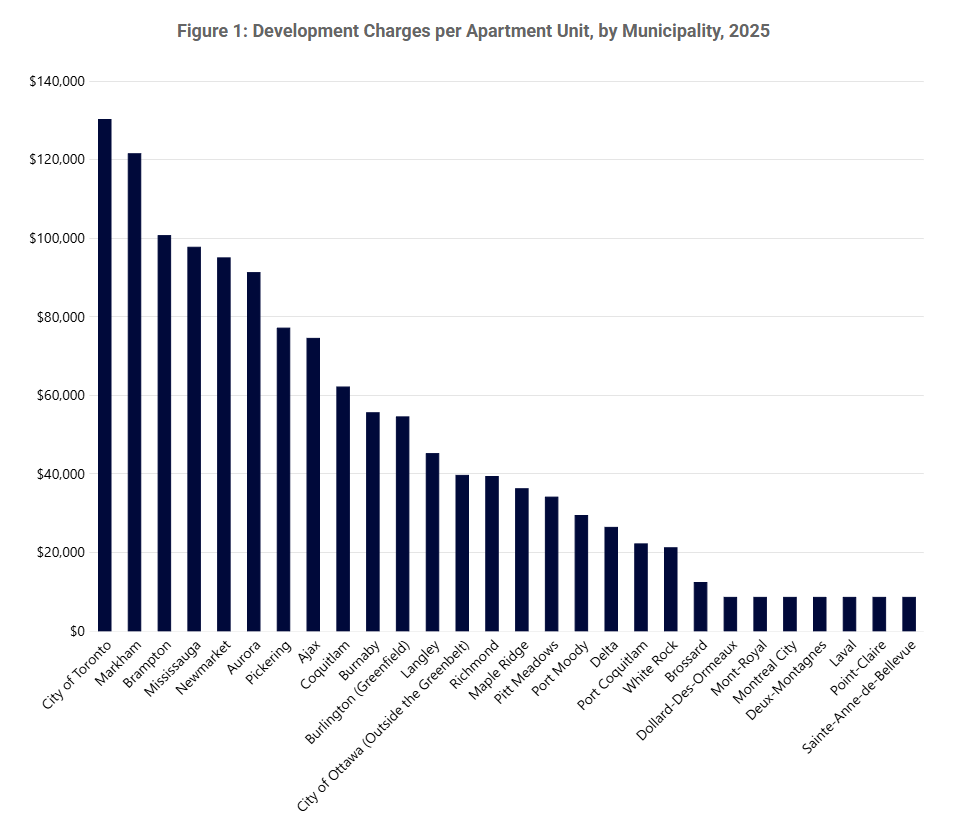

#1 Development Charge and Infrastructure Funding Reform

Development charges and the alphabet soup of municipal housing construction-taxes are too high and need to come down. The “growth should pay for growth” mantra is based on a sleight-of-hand, which conflates housing growth with population growth, in a country where almost all net population growth comes from international migration. As we noted in an earlier piece, this unfairly disproportionately places those up-front settlement costs on a small segment of society while also slowing the very homebuilding we need to support a larger population:

Although the benefits of immigration to our labour market, our economy, and our social fabric are widely distributed, the up-front infrastructure costs are not widely shared, but rather placed on a small subset of new homebuyers and renters, including the newcomers themselves.

We need to have an honest discussion about how fast Canada’s population should grow, who benefits from that growth, and who should bear the infrastructure costs associated with that growth. The linguistically vague rhetorical shield of “growth should pay for growth” avoids that conversation and allows for population growth-related expenses to be disproportionately placed on the young.

While immediate development-charge relief is needed, the long-term goal should be to enact structural reforms that reduce the costs of building new infrastructure. Financing costs are where the biggest savings are. Paying for infrastructure with development charges places the financing costs for that infrastructure on residential mortgages and construction loans, which carry much higher interest rates than government debt. Instead, infrastructure should be financed through government debt, then repaid through a revenue stream; e.g., financing water and wastewater infrastructure with government debt, adding a surcharge to water bills to repay that debt, and removing that surcharge once the debt is fully repaid. If this model were implemented nationwide, the annual savings in interest costs would be in the billions.

In short, it is possible to fund infrastructure without massive development charges, as a recent CMHC release shows.

Figure 1: Development Charges per Apartment Unit, by Municipality, 2025

Source: CMHC.

Our wish list for development charge reform includes:

Financing infrastructure at government bond rates, rather than residential mortgage and construction loan rates, through mechanisms such as municipal service corporations for water and wastewater, and reallocating gas taxes and vehicle taxes as a revenue stream to pay for roads.

Deferred payment of development charges to occupancy for purpose-built rental projects, to avoid having to finance development charges on construction loans. For ownership-based projects, instituting a direct-to-buyer model for development charges, similar to how HST is paid for on new homes, and making those development charges exempt from HST, PST, and land-transfer taxes. This would substantially reduce the size of construction loans needed to start a project, defer payment of development charges, and eliminate the existing development-charge tax-on-tax, where embedded development charges are assessed HST and land transfer taxes. It is one thing to require a new homebuyer to help fund the construction of a local library; it is another thing entirely to charge them sales taxes on their contributions.

A whole host of technical changes to the methodology for calculating development charge rates.

#2 Stop Taxing New Housing Construction Like Cigarettes

Federal law declares that housing is a human right, yet Canadian governments tax new housing construction at rates normally associated with alcohol and tobacco. Reforming development charges would go a long way to fixing that, but other reforms are needed, including:

Expanding the federal First-Time Home Buyers’ GST Rebate to all purchases of new primary residences.

Exempting new homes from land transfer taxes. British Columbia does this for homes valued under $1.1 million; Ontario offers no equivalent exemption.

#3 Acknowledge the Need for Family-Sized Homes in Housing Policy

Canadian housing policy is plagued by “a unit is a unit is a unit” thinking, where a small studio apartment is considered functionally equivalent to a 3-bedroom home, leaving the country with a massive shortage of homes suitable for raising children. Ontario’s Building Faster Fund provides the same benefits to cities that build shoebox condos as family-sized homes; municipal growth plans often use unrealistic assumptions on family formation to reduce estimates on how many larger homes are needed. And for all the complaints about those shoebox condos, municipalities in Ontario typically charge higher rates of development charges on larger apartments. In many parts of the country, the 3-bedroom “starter” family home has been legislated out of existence due to bad policy design and “a unit is a unit is a unit” thinking. This needs to change.

#4 Institute Building Code and Regulatory Reform

In many parts of Europe, family-friendly three-bedroom homes are apartment units, with fantastic layouts and designs that suit a wide range of families. Unfortunately, those homes are illegal to build anywhere in Canada. For example, the book “Impossible Toronto” lists at least 14 regulatory reasons why fantastic European courtyard-style apartments cannot be built here. Some of those reasons have to do with the building code, such as rules on staircases that limit the geometry of floor layouts, making adding a third bedroom impractical. Poorly designed regulations and a failure to adhere to international standards cause North American elevators to cost five times as much as their European counterparts.

Many of the other reasons those apartments can’t be built here involve zoning and land use.

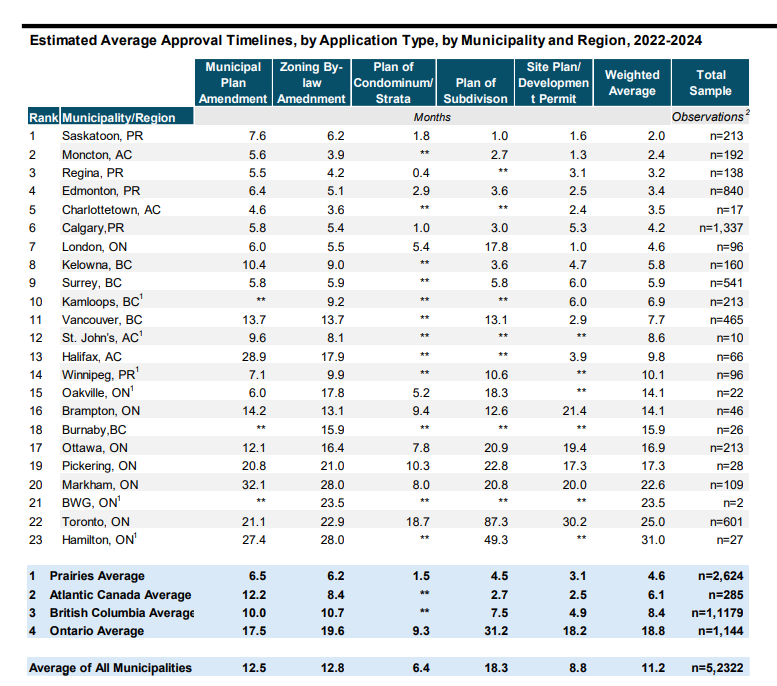

#5 Zoning, Land Use, and Approvals Reform

Height restrictions, angular planes, anti-density rules, and a whole host of other municipal red tape prevent the construction of family-friendly housing. Overly complex rules also advantage larger developers who have the resources to cut through the red tape and to obtain special permissions where needed. Differences between municipalities, or even different parts of a municipality, create barriers to entry for builders and limit our ability to use factory-built approaches and other modern methods of construction, because every new home has a different set of conditions to which it must adhere.

Having hundreds of municipalities in a province, each come up with its own bespoke set of rules, is a massive waste of resources that makes housing more expensive and our cities worse places to live. Canadian provinces could look to Japan for inspiration, where a higher level of government sets overall zoning rules, and municipalities focus on implementing them in ways appropriate to the local context.

Municipal approval processes are also broken in many parts of the country; a project that might take two or three months to get approved in Edmonton could take two to three years to be approved in Hamilton.

Figure 2: Estimated Average Approval Timelines

Source: Canadian Home Builders’ Association 2024 Municipal Benchmarking Study

Municipal land planning is also in desperate need of reform. Urban growth boundaries are set in ways that do not acknowledge the extent of population growth, the need for more family-friendly housing, and that some land within urban growth boundaries that cities earmark for development is too often either environmentally sensitive or at high flood risk and therefore inappropriate for development. Better hazard mapping is needed, along with long-term planning that adequately acknowledges the realities of population growth and aging.

#6 Fixing Broken Population Projections

Our current planning and approvals systems are too heavily reliant on population forecasting; we should be making our systems more elastic to unexpected changes in population growth. However, there will always be a need for population forecasting in planning, particularly when making infrastructure investments.

Ontario’s population projections do not work. The forecasts continue to make predictable errors in their approach to intraprovincial migration (that is, families moving from one community in the province to another), thereby locking in housing shortages.

Our wish for 2026 is population projections that adequately capture the dynamics of families moving from one community to another.

#7 Institute the MURB Tax Provision

During the last election, the federal Liberals ran on four big housing promises. One of those promises, the First-Time Home Buyers’ GST Rebate, was part of this still-unpassed Bill C-4, which is stuck in the Senate that does not meet again until February. Two others, Build Canada Homes and development-charge reductions, are underway, albeit in reduced form. The fourth commitment, reintroducing the 1970s-era MURB provision to facilitate the building of small- and mid-rise apartments, has fallen between the cracks.

A well-designed MURB program could help build a housing type we need far more of; our wish for 2026 is that the federal government make good on their commitment.

#8 Condo Financing Reform

A condo financing model that relies heavily on pre-construction sales from investors can attract capital when home prices are rising rapidly, though it has been criticized for creating units that are more suitable as investments than homes. Our view is that this relationship is real but overblown; the shrinkflation of apartments has more to do with cost pressures than with how construction is financed. That said, there is no doubt that an investor-driven model has at least some impact on unit designs.

However, when unit prices are not rising, pre-construction sales to investors evaporate, and the market seizes up. There is a real need for policy reforms to create condo markets that are less reliant on Mom-and-Pop investors for capital, so that condo financing is not reliant on home prices rising faster than incomes.

#9 Policy Differentiation Between New and Existing Homes

The title of our piece New Homes are the Solution: Policy Must Treat Them Differently says it all. Policies that lower the cost of construction of new homes, or make it easier to attract capital to housing construction, can get more homes built and lower prices and rents. Policies that encourage resale purchases cause prices to rise and create housing bubbles. Yet too often housing policies fail to make this distinction. Or, worse, impose higher taxes on new homes than on resale purchases.

Smart policy design can fix this. For example, Australia recognized that buying up existing homes and providing financing for new homes are two substantially different activities, with differing impacts on the housing supply. As such, their foreign buyer ban exempts new or near-new purchases by foreign buyers to help increase the amount of capital available to builders.

All order of governments should reassess their policies and determine where they’re creating the conditions to build and where they’re simply inflating the value of existing assets, and reform rules and regulations accordingly.

#10 Identifiable Government Vision and Key Performance Indicators

One of the challenges of providing policy advice to governments is that it is not clear what those governments are trying to accomplish. For instance, it is unclear whether or not the federal government believes in the future of middle-class homeownership. Housing policies designed for a nation of renters are fundamentally different from those that aim to create a country where home ownership is widely attainable (while still ensuring that renting is a viable option for the middle-class).

Our governments lack well-defined housing goals and objectives. This filters down to the program level as well. Five years from now, there will be no way to assess whether or not Build Canada Homes was a success or not, since the program lacks any quantifiable goals or performance metrics.

Governments need to have a clear vision, quantifiable goals, and performance tracking. Our governments lack all of these when it comes to housing. Our wish for 2026 is that governments begin to inform Canadians on what they are trying to accomplish and be transparent on how they are performing against those goals.

That is probably too much to wish for, but the holidays are where dreams become true.